One casualty of the palm oil industry: An orangutan mother, shot 74 times

By Hannah Beech

29 June 2019

BUNGA TANJUNG, Indonesia (The New York Times) – The men came at Hope and her baby with spears and guns. But she would not leave. There was no place for her to go.

When the air-gun pellets pierced Hope’s eyes, blinding her, she felt her way up the tree trunks, auburn-furred fingers searching out tropical fruit for sustenance.

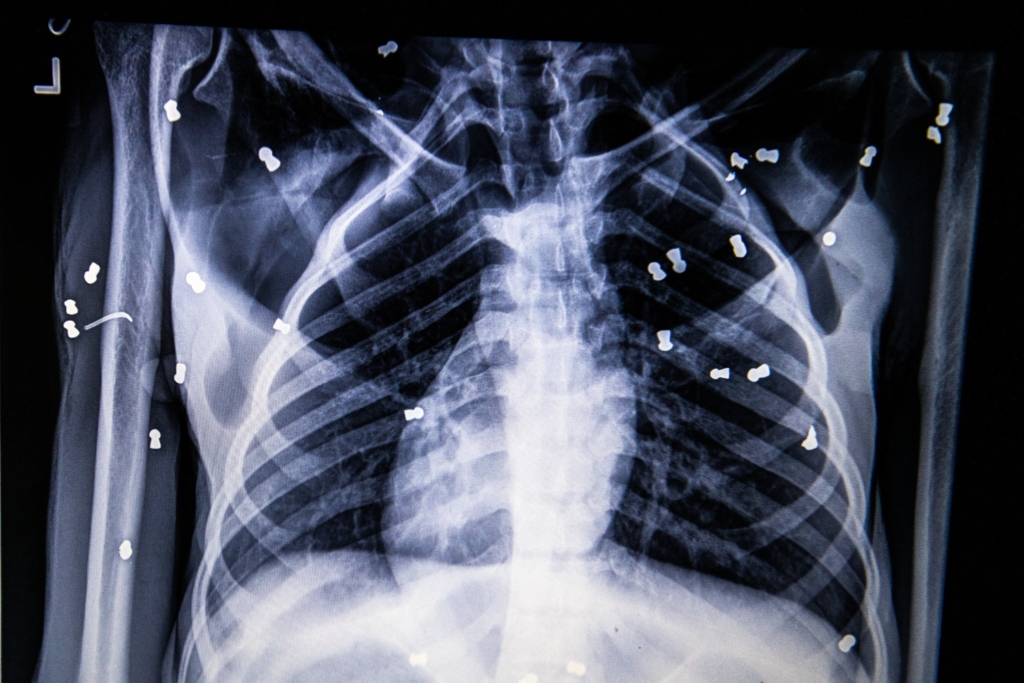

By the end, Hope’s torso was slashed with deep lacerations. Multiple bones were broken. Seventy-four pellets were lodged in her body. Her months-old baby had been ripped away.

Hope, who was named at a rehabilitation center, is a Sumatran orangutan — a critically endangered animal that scientists warn could be the first major great ape species to go extinct. As jungle and swamp are cleared for palm oil plantations, orangutans, whose name means “people of the forest” in Malay, are losing the very habitat that gives them their identity. [Sadly, this is all too common, cf. Four Indonesian farmers charged in killing of orangutan that was shot 130 times – “All took turns shooting at the orangutan”. –Des]

All around the Indonesian island of Sumatra, charred landscapes of blackened tree stumps and singed earth attest to the devastation wrought by humans.

“Twenty thousand hectares are cleared and a couple trees are left and the orangutan looks around and says, ‘What happened to my forest?’” said Ian Singleton, the director of the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Program.

Two nations, Indonesia and Malaysia, provide the world with more than 80 percent of the palm oil used in everything from biofuel and cooking oil to lipstick and chocolate. Last September, amid concerns over diminishing habitat for endangered species and dangerous carbon emissions from mass burnings to clear land, Indonesia stopped issuing new licenses for palm oil plantations.

But as Hope’s plight shows, directives issued in air-conditioned government offices can mean little in poor villages. The global appetite for palm oil is still voracious.

“They say there is a moratorium, but I can see with my own eyes that land is being lost every day,” said Krisna, a coordinator for the Human Orangutan Conflict Response Unit, a group based on Sumatra that has rescued more than 170 injured orangutans since 2012. […]

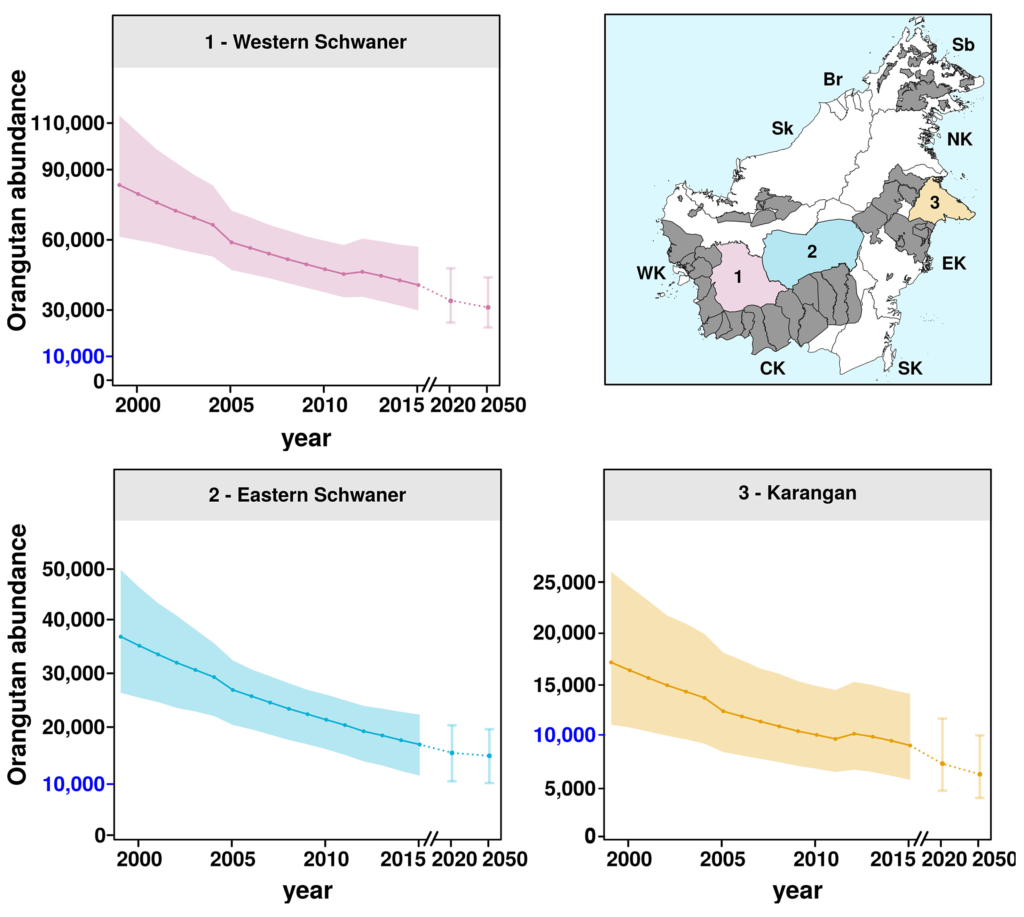

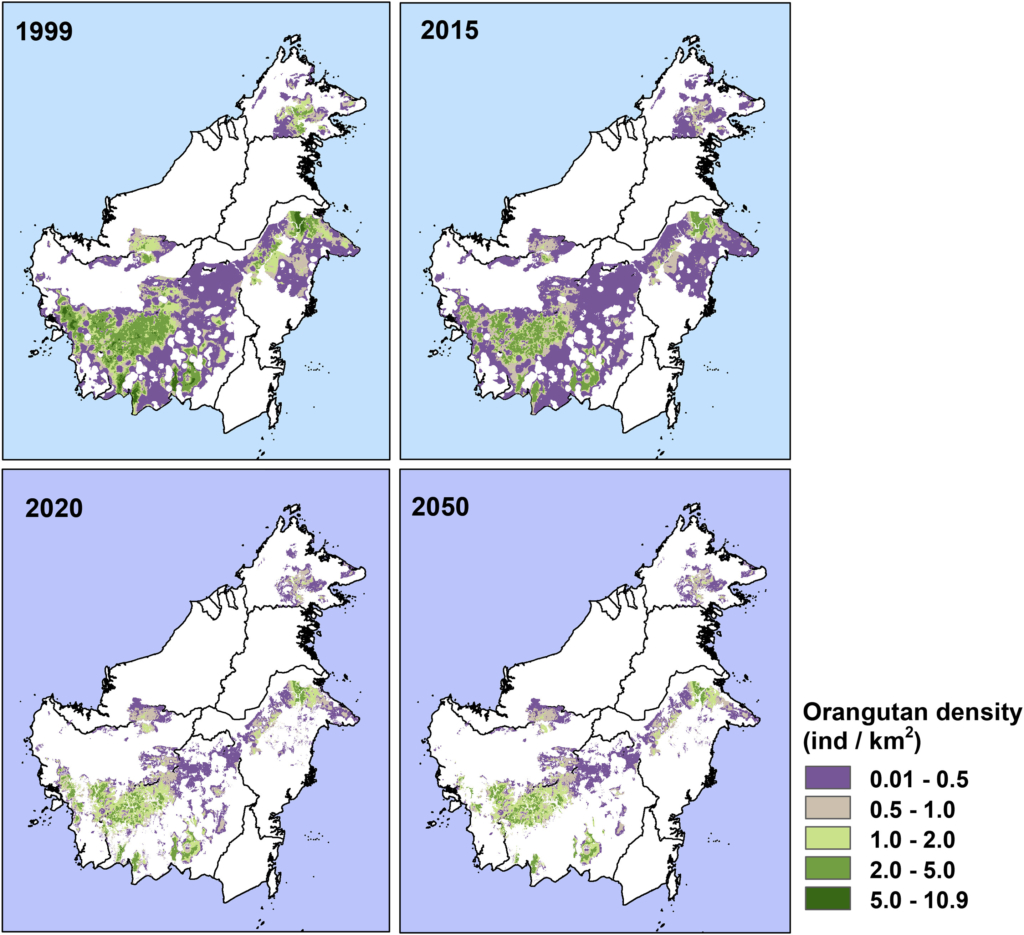

From 1999 to 2015, the orangutan population on the island of Borneo declined by more than 100,000, researchers reported in Current Biology, a scientific journal. [more]

One Casualty of the Palm Oil Industry: An Orangutan Mother, Shot 74 Times

Global demand for natural resources eliminated more than 100,000 Bornean orangutans

ABSTRACT: Unsustainable exploitation of natural resources is increasingly affecting the highly biodiverse tropics [1, 2]. Although rapid developments in remote sensing technology have permitted more precise estimates of land-cover change over large spatial scales [3, 4, 5], our knowledge about the effects of these changes on wildlife is much more sparse [6, 7]. Here we use field survey data, predictive density distribution modeling, and remote sensing to investigate the impact of resource use and land-use changes on the density distribution of Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus). Our models indicate that between 1999 and 2015, half of the orangutan population was affected by logging, deforestation, or industrialized plantations. Although land clearance caused the most dramatic rates of decline, it accounted for only a small proportion of the total loss. A much larger number of orangutans were lost in selectively logged and primary forests, where rates of decline were less precipitous, but where far more orangutans are found. This suggests that further drivers, independent of land-use change, contribute to orangutan loss. This finding is consistent with studies reporting hunting as a major cause in orangutan decline [8, 9, 10]. Our predictions of orangutan abundance loss across Borneo suggest that the population decreased by more than 100,000 individuals, corroborating recent estimates of decline [11]. Practical solutions to prevent future orangutan decline can only be realized by addressing its complex causes in a holistic manner across political and societal sectors, such as in land-use planning, resource exploitation, infrastructure development, and education, and by increasing long-term sustainability [12].

Global Demand for Natural Resources Eliminated More Than 100,000 Bornean Orangutans