An investigation into how India dismantled its main defence against drought – “By shifting the focus to farm irrigation, the government is taking water conservation efforts back by 20 years”

By Aarefa Johari and Nithya Subramanian

1 July 2019

(Quartz) – At the height of the June summer in Madhya Pradesh, Mannubai Chamariya heaved boulders from the banks of a dry stream to a site where other workers arranged them in a tiled wall, filling the gaps with cement.

The work was arduous but Chamariya and the others did not mind it.

They were building a small check dam in the hope that it would bring water to their parched fields—and prosperity to their lives.

“Normally this nala [stream] is full only during the monsoon,” said Chamariya, a woman in her 40s who lives in Sangvi village in Bhikangaon block and grows cotton and soyabean in its black loamy soils. “But this dam will help us get water even in the other seasons.”

Such dams usually have sluices or metal gates that can be opened to allow the flow of excess water when the stream is full.

“The gates help silt to flow out with the water,” said Radheshyam Patel, an agricultural engineer with Samaj Pragati Sahayog, the non-profit organisation that is helping the villagers build the dam. “Without them, streams get clogged with siltation and their water storage capacity reduces very quickly.”

This makes gated dams crucial for water conservation.

But the district administration, which is funding the dam, nearly did not sanction money for the gates—all because of a controversial shift in India’s water conservation policy under the Narendra Modi government.

From integration to irrigation

The check dam under construction in Bhikangaon block is part of a watershed development project under the central government’s integrated watershed management programme.

The integrated watershed management programme, started in 2009, aims to fight drought in India by holistically conserving water along with soil and forests, through hundreds of projects, each operating at the level of a watershed spread over 5,000 acres of land.

For decades, this integrated approach has been widely recognised around the world as a successful method of ecological conservation in water-scarce regions.

In India, experts say it is absolutely essential.

Watersheds are basin-like areas that collect rainfall water, store a part in the soil and drain the rest into streams and rivers.

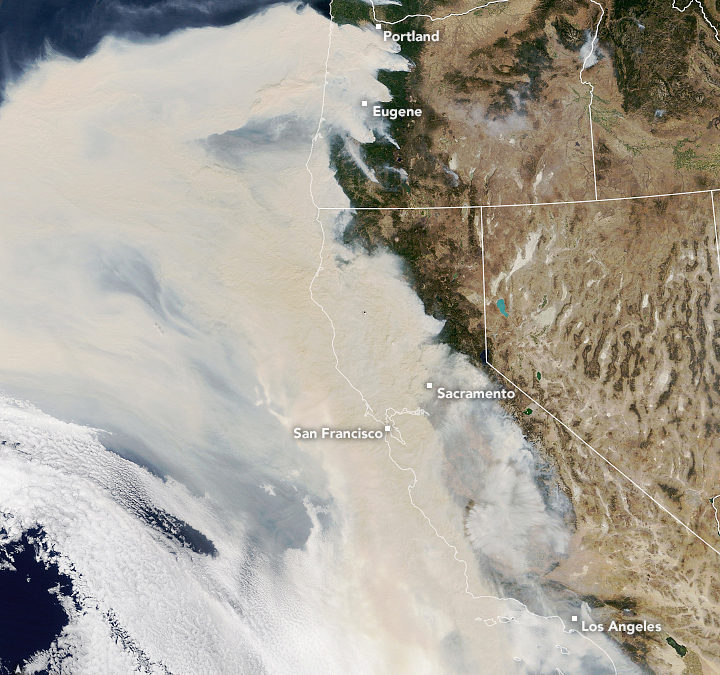

More than two-thirds of the country’s area is covered by drylands and 53% of its agriculture is dependent on the rains. With climate change affecting weather systems, the Indian monsoon is becoming more erratic. The pre-monsoon showers this year have been the second-lowest in 65 years. In the third week of June, 43.62% of India was facing drought conditions. Chennai, the country’s fourth-largest city, is running out of water.

District officials have only been giving sanctions and funding for structures that result in direct irrigation outcomes, like dams without gates. They are denying permissions for structures meant for soil conservation.

Radheshyam Patel, agricultural engineer with non-profit organisation Samaj Pragati Sahayog

India badly needs to conserve every drop of water—and watershed management is considered the best way to do it.

But the integrated watershed management programme is dying a slow death.

One year after the Modi government was elected, in July 2015, it launched a new scheme for farmland irrigation called the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana. The aim of the scheme was pithily summed up in slogans: “Har Khet Ko Pani”—water for every farm—and “Per Drop More Crop.”

Experts say this narrow focus on farm irrigation is a sharp departure from the broader framework of watershed management, which not only seeks to conserve water, but also tries to rejuvenate the local ecology. It also promotes sustainable uses of water by weaning away farmers from water-intensive crops.

The Modi government has not ended the integrated watershed management programme—it was made a part of the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana as its watershed development component. But for all practical purposes, it is being phased out.

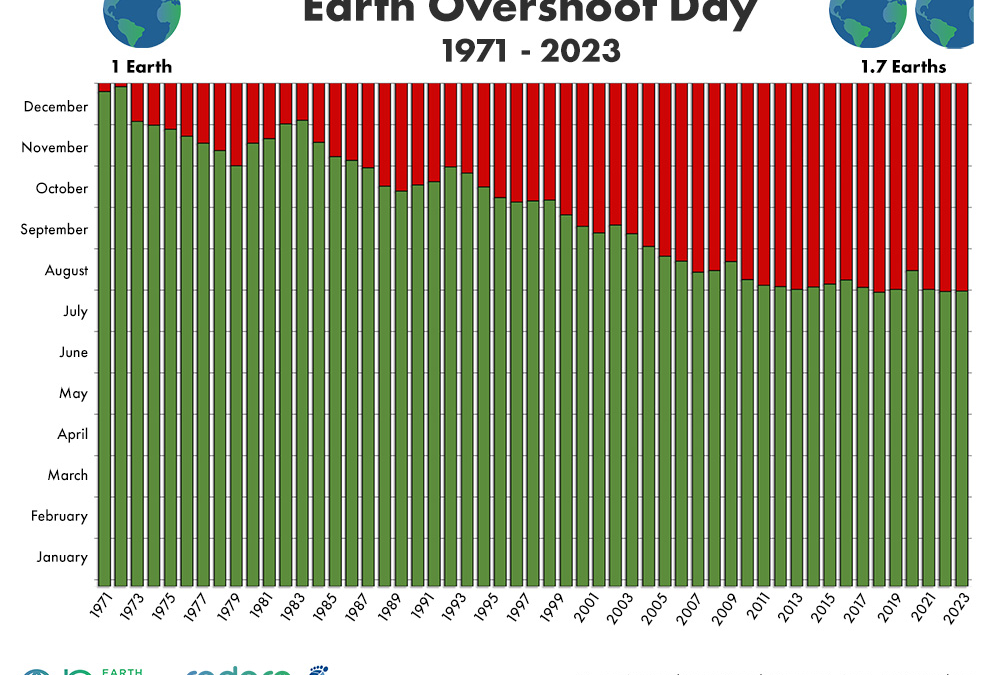

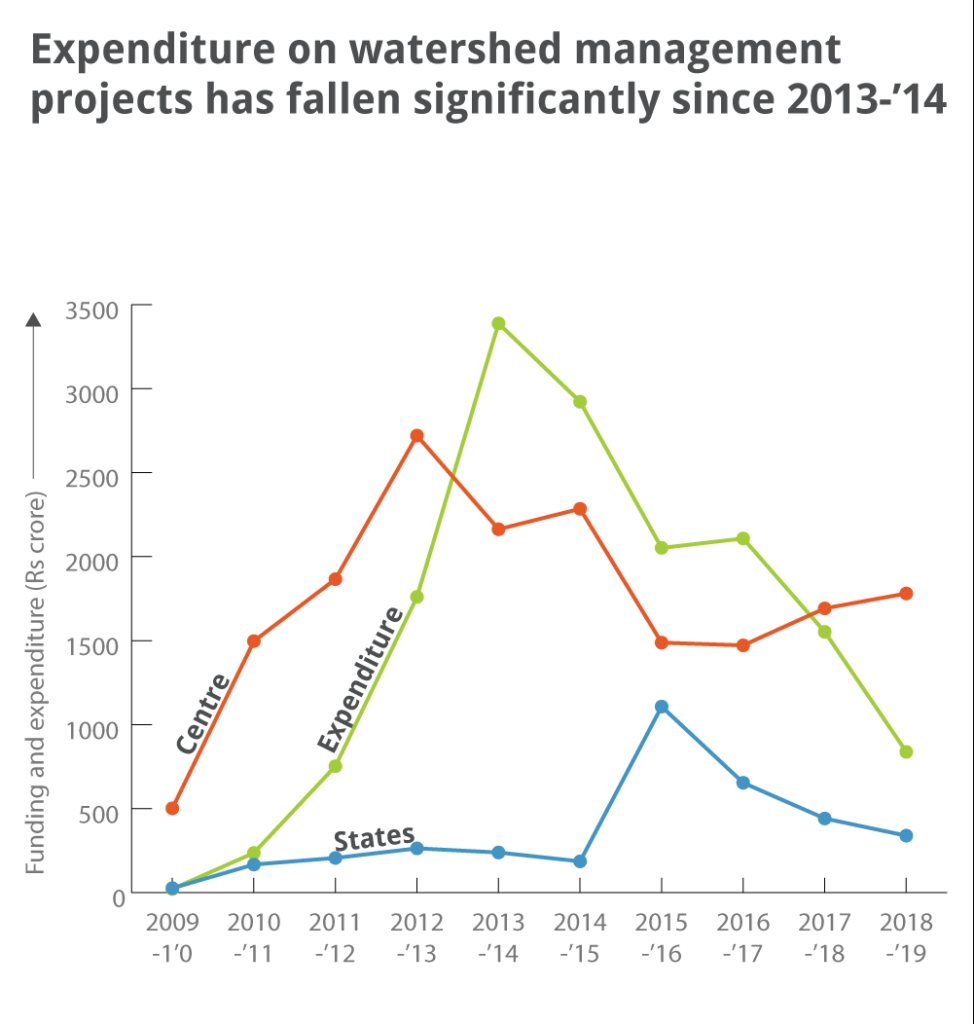

In the last four years, central funding to the programme has drastically dropped, Scroll.in’s analysis of government expenditure shows. From Rs2,284 crore ($330 million) allocated in 2014-15, central funds for watershed work shrunk by 35% to Rs1,487 crore in the first year of the policy shift.

Agricultural experts believe the programme’s best features have been compromised. In Bhikangaon, for instance, after the integrated watershed management programme was merged with PMKSY, “district officials have only been giving sanctions and funding for structures that result in direct irrigation outcomes, like dams without gates,” said Radheshyam Patel, the agricultural engineer. “They are denying permissions for structures meant for soil conservation.”

Worse, since 2016, the government has stopped sanctioning new watershed projects. From watershed development work over 39 million hectares of land, the programme’s aim has narrowed down to bringing just 11.5 lakh hectares of land under irrigation coverage.

“By shifting the focus (to farm irrigation), the government is taking water conservation efforts back by 20 years,” said Vijay Shankar, a founding member of Samaj Pragati Sahayog, the non-profit organisation that is implementing the 5,046-hectare watershed management project in Bhikangaon. [more] […]

An investigation into how India dismantled its main defence against drought