“Day Zero” in India looming for millions

By Dr. Jeff Masters

6 June 2019

(Weather Underground) – In early 2018, a three-year drought pushed Cape Town, South Africa, within weeks of experiencing “Day Zero”—the day when the city would run out of water and the taps be shut off. Fortunately, extreme water conservation efforts and the arrival of timely rains pushed “Day Zero” back indefinitely.

But in India, “Day Zero” has already arrived for over 100 million people, thanks to excessive groundwater pumping, an inefficient and wasteful water supply system and years of deficient rains. “Day Zero” is expected to arrive for millions more in India by 2020, when groundwater supplies are predicted to run out for 100 million people in the northern half of India.

“Large parts of India have already been living with ‘Day Zero’ for a while now,” said Mridula Ramesh in a 2018 interview with Reuters. Mridula is author of the 2018 book, The Climate Solution: India’s Climate Change Crisis and What We Can Do About It. “Much of it is because of bad management. Most cities lose between a third and a fifth of their water from pilferage or leakage through antiquated pipes, and we don’t treat and reuse wastewater enough,” she said.

Over 12% of India’s population–163 million people of 1.3 billion–live under “Day Zero” conditions, with no access to clean water near their home, according to a 2018 WaterAid report. That is the most of any country in the world. With the taps dry, people are forced to dig ever-deeper wells or buy water.

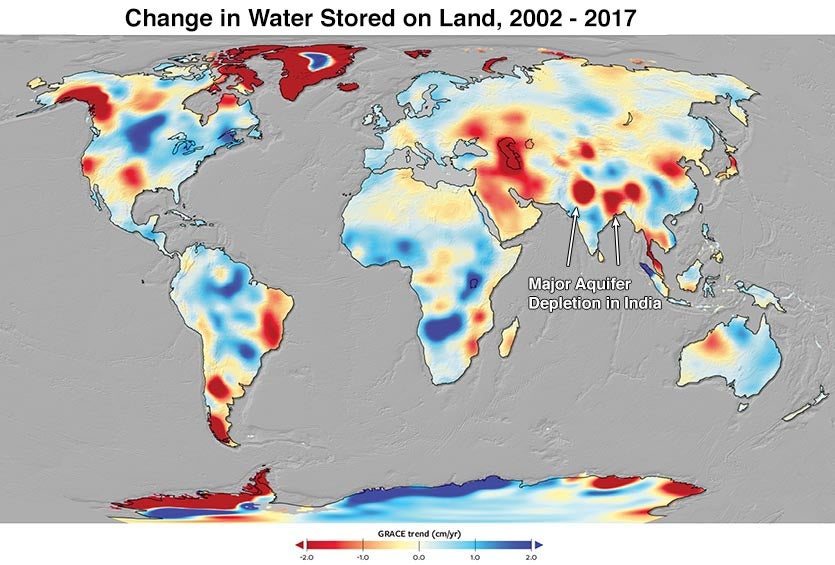

The number of people in India experiencing “Day Zero” is set to grow significantly by 2020, according to a startling report released in 2018 by Niti Ayog, India’s federal think tank. “Supply gaps are causing city dwellers to depend on privately extracted ground water, bringing down local water tables,” the report says. “In fact, by 2020, 21 major cities, including Delhi, Bengaluru (formerly called Bangalore), and Hyderabad, are expected to reach zero groundwater levels, affecting access for 100 million people.” Loss of groundwater supplies will force people in the affected cities to rely on rainwater harvesting and water piped from rivers–sources that are inadequate to meet the demand. Groundwater supplies 40% of India’s water needs, including more than 60% of irrigated agriculture and 85% of domestic water use. India accounts for 12% of global groundwater use. [more]