Climate chaos is coming, and the Pinkertons are ready – As they see it, global warming stands to make corporate security as high-stakes in the 21st century as it was in the 19th

By Noah Gallagher Shannon

10 April 2019

(The New York Times Magazine) – The Pinkertons wanted me to picture myself in a scene of absolute devastation. “A hurricane just wipes out everything, and you need to feed your children,” Andres Paz Larach said. The power grid is down, shipments of food are cut off, the water is no longer potable — how do you get what you need to survive? What risks do you take? It was a hot early morning in March, and we were driving through a pine forest high in the mountains surrounding Santa Ana Jilotzingo, 25 miles northwest of Mexico City. Our Suburban, equipped with bulletproof windows and reinforced doors, labored slowly over the dirt road, which appeared to have been washed out by a recent thunderstorm.

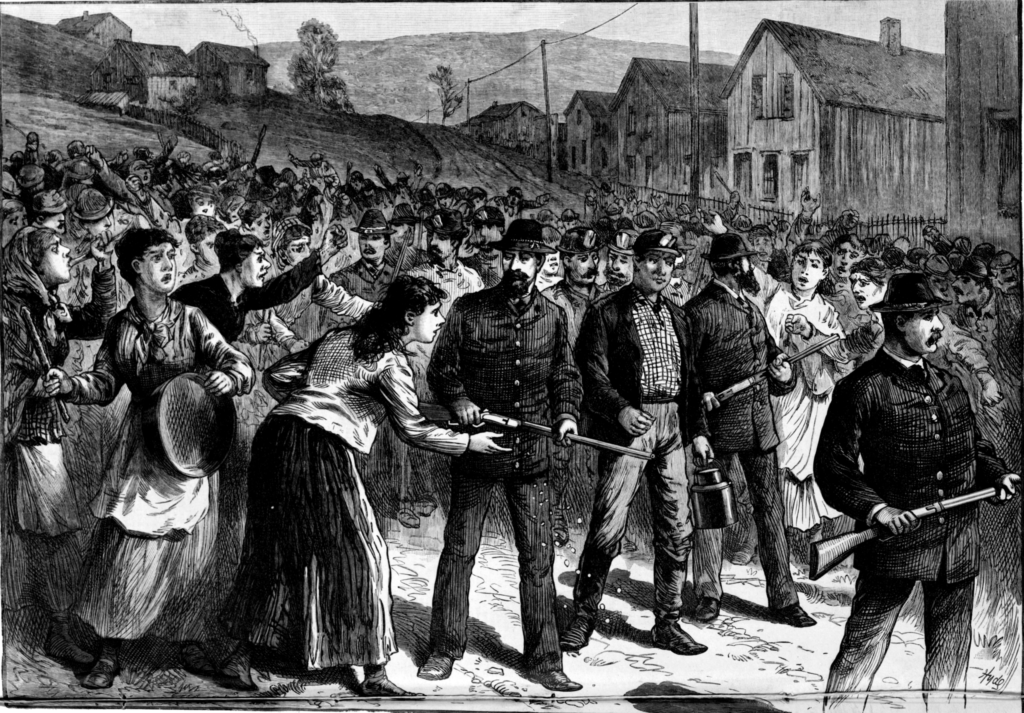

For much of the previous hour, Paz Larach and two other executives from Pinkerton, Carlos Manuel López Portillo Maltos and Paul Rakov, had been explaining the company’s philosophy of risk management. Now over 150 years old, having long outlived its reputation as Andrew Carnegie’s personal militia, the agency has evolved into a modern security firm. Over the last decade or so, Pinkerton began noticing a growing set of anxieties among its corporate clients about distinctly contemporary plagues — active shooters, political unrest, climate disasters — and in response began offering data-driven risk analysis, in addition to what they’re more traditionally known for. Dressed in an untucked powder blue oxford and round, rimless sunglasses, Paz Larach, the firm’s senior vice president in charge of the Americas, paused before affecting a look of brutal candor. “You’re going to turn to desperate measures,” he said. Everybody will. The other Pinkertons nodded.

I was seated in the rear row next to Rakov, a marketing officer who, at 51, had recently shifted his career from more traditional P.R. to Pinkerton. He was now fully fluent in the language of tactical response. He chimed in to observe that preparing for a disaster can carry its own risks. He gave the example of a drought. “If a client has food and water and all the other stuff,” he said, “then they become a target.” López Portillo and Paz Larach uttered small words of consensus in Spanish, while scanning through email on their phones. “And if and when desperate people discovered that cache of water and food,” he continued, it was the Pinkertons’ job to protect it at whatever cost. […]

López Portillo, who until then had been jovial if diplomatic in answering my questions, turned solemn, his eyes glancing around the vaulted ceiling. He said he worried about his children, and what sort of world he might be leaving them. But his fear, he clarified, wasn’t exactly that they wouldn’t learn to adapt; it was that he, their father, didn’t know what adaptation would look like. He said that he feared variables he didn’t know how to calculate, variables he couldn’t conceive of yet.

When López Portillo finished, Paz Larach admitted that thinking that far out was still difficult for him. He was 33 and just married. What the most immediate future held for him was a new home in Miami, where he and his wife had just bought an apartment on the water. It had always been their dream. When I asked him about sea-level rise — something with which Miami is practically synonymous — he paused for a moment, then said, “We know it’s a risk, but we looked at it and decided it was worth it.” And anyway, the apartment wouldn’t be ready until 2021. They’d deal with it then. [more]