Children suffer most from deadly coal pollution in one of Earth’s most polluted cities – “I no longer know what a healthy lung sounds like”

By Beth Gardiner

26 March 2019

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (National Geographic) – Coal is everywhere in Mongolia’s frigid capital. It sits beneath the towering smokestacks of power plants in piles as big as football fields. Drivers haul it through town in the open beds of pickup trucks. Vendors stack yellow bags of the stuff along roadsides, and jagged pieces spill from metal buckets in the round felt yurts where the poorest families burn it to keep out the bitter cold.

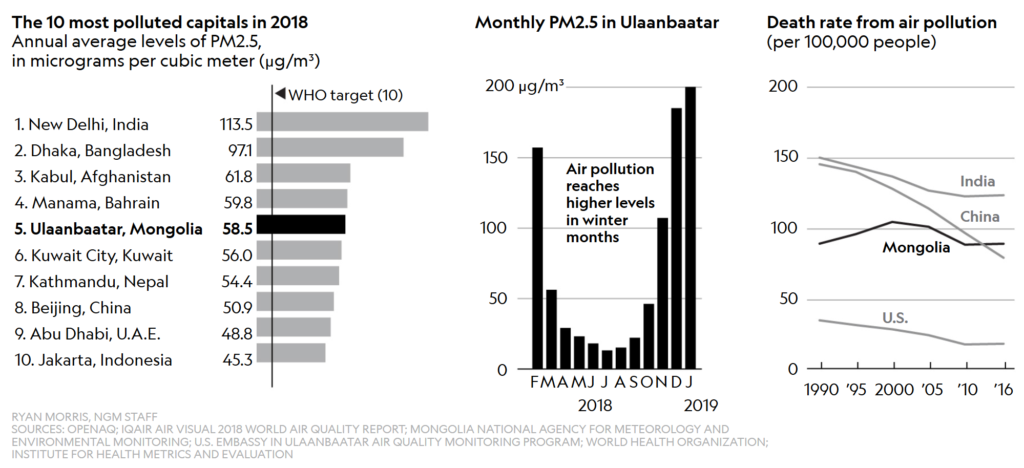

The smoke in Ulaanbaatar is at times so thick that people and buildings are visible only in outline. Its smell is acrid and inescapable. The sooty air stings throats and wafts into the gleaming modern office buildings in the center of town and into the blocky, Soviet-style apartment towers that sprawl toward the mountains on the city’s edges. On bad days, handheld pollution monitors max out, as readings soar dozens of times beyond recommended limits. Levels of the tiniest and most dangerous airborne particles, known as PM-2.5, once hit 133 times the World Health Organization’s suggested maximum.

Mongolia’s pollution problem is a more severe version of one playing out around the world. From the United States and Germany to India and China, air pollution cuts short an estimated 7 million lives globally every year. Coal is one of the major causes of dirty air—and of climate change.

In Mongolia, at least for now, coal is essential to surviving the brutal winters. But the toll it takes is steep.

This winter authorities closed the capital’s schools for two full months, from mid-December to mid-February,in a desperate attempt to shield children from the toxic air. It’s unclear how effective that measure is. Hospitals are stretched far beyond capacity, as pneumonia cases, particularly among the youngest, spike every winter.

“I no longer know what a healthy lung sounds like,” says Ganjargal Demberel, a doctor who makes house calls in a neighborhood of yurts—known in Mongolia as gers—tucked into the jagged brown hills in the city’s northeastern corner. “Everybody has bronchitis or some other problem, especially during winter.” [more]