Widespread marine oxygen declines are stressing sensitive species – “It’s potentially very dire”

By Laura Poppick

25 February 2019

(Scientific American) – Escaping predators, digestion and other animal activities—including those of humans—require oxygen. But that essential ingredient is no longer so easy for marine life to obtain, several new studies reveal.

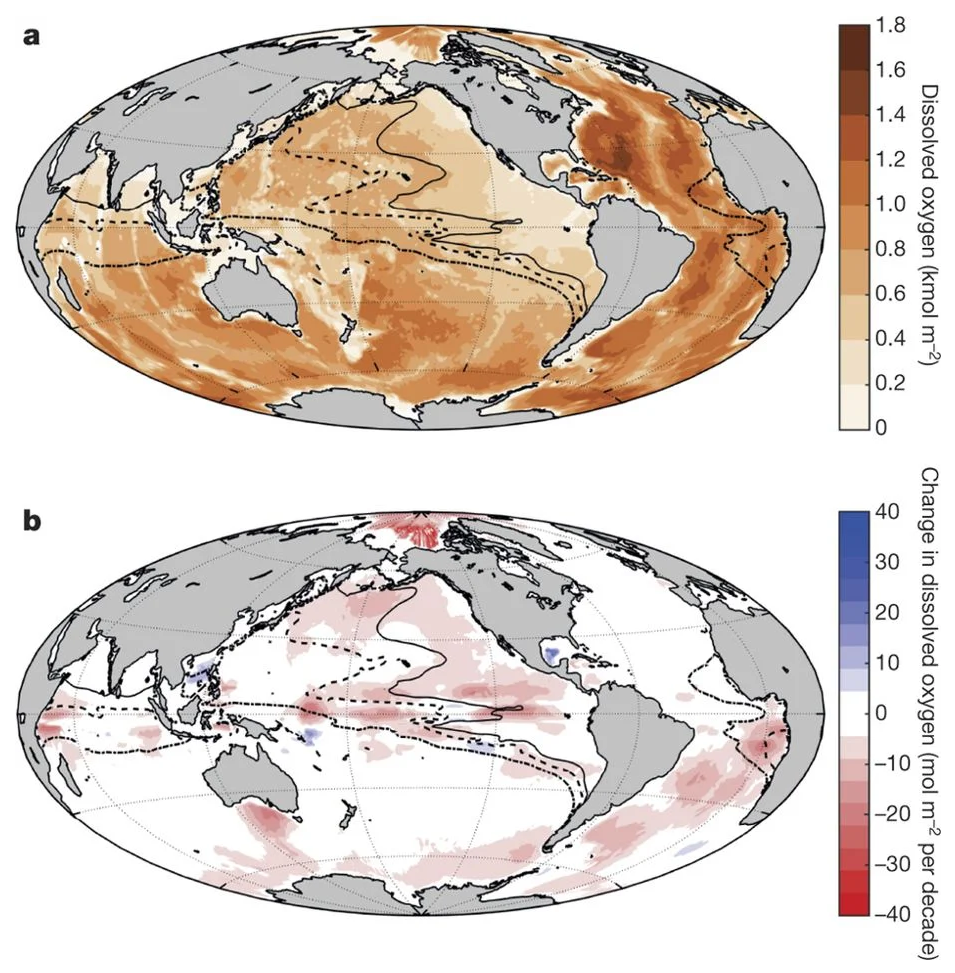

In the past decade ocean oxygen levels have taken a dive—an alarming trend that is linked to climate change, says Andreas Oschlies, an oceanographer at the Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany, whose team tracks ocean oxygen levels worldwide. “We were surprised by the intensity of the changes we saw, how rapidly oxygen is going down in the ocean and how large the effects on marine ecosystems are,” he says.

It is no surprise to scientists that warming oceans are losing oxygen, but the scale of the dip calls for urgent attention, Oschlies says. Oxygen levels in some tropical regions have dropped by a startling 40 percent in the last 50 years, some recent studies reveal. Levels have dropped more subtly elsewhere, with an average loss of 2 percent globally. […]

Some coastal regions around the equator naturally are low-oxygen hotspots because they contain nutrient-rich waters where bacterial blooms consume oxygen as they break down dead marine life. But shifts in ecosystems elsewhere—including in the open ocean and around the poles—especially surprises and concerns Oschlies and others because these regions were not considered as vulnerable. Climate models projecting future change have also routinely underestimated the oxygen losses already observed around the world’s oceans, he and his colleagues reported in Nature last year—another reason why this trend calls for more attention, he says.

The effects of even very subtle dips in oxygen on where zooplankton—animals at the base of the food web—congregate in the water column were documented in a December 2018 Science Advances report. “They are very sensitive,” says study leader Karen Wishner, an oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island, even more so than she had expected. Some species swim to deeper, cooler water with more oxygen. “But at some point it doesn’t work for them to just go deeper,” she says, because it can be harder to find food or reproduce in lower-temperature waters. Many predators—including fishes, squids and whales—either eat zooplankton or eat fishes that eat zooplankton, so the ways zooplankton cope will have ramifications up the food web, she notes. [more]

Eventually this must get to land based organisms too, I would think. That was pointed out in my ecology classes I took in the 70’s