Heatwaves sweeping oceans “like wildfires”, scientists reveal – “You see the kelp and seagrasses dying in front of you. Within weeks or months they are just gone, along hundreds of kilometres of coastline.”

By Damian Carrington

4 March 2019

(The Guardian) – The number of heatwaves affecting the planet’s oceans has increased sharply, scientists have revealed, killing swathes of sea-life like “wildfires that take out huge areas of forest”.

The damage caused in these hotspots is also harmful for humanity, which relies on the oceans for oxygen, food, storm protection and the removal of climate-warming carbon dioxide the atmosphere, they say.

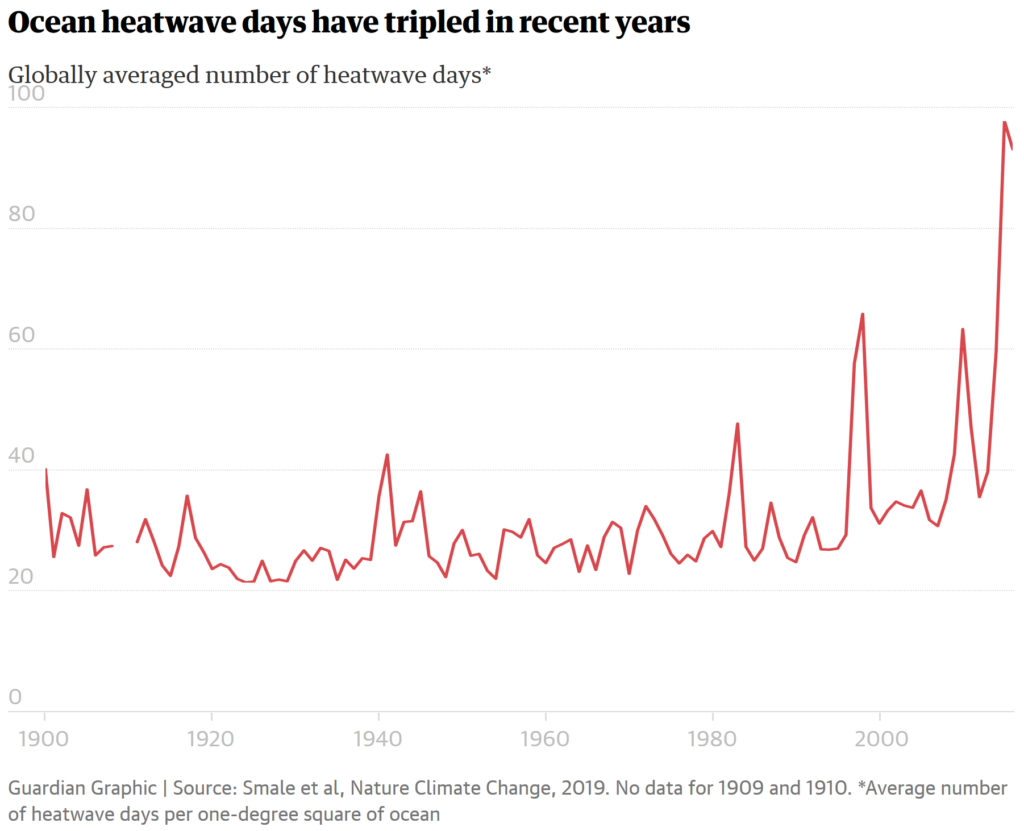

Global warming is gradually increasing the average temperature of the oceans, but the new research is the first systematic global analysis of ocean heatwaves, when temperatures reach extremes for five days or more.

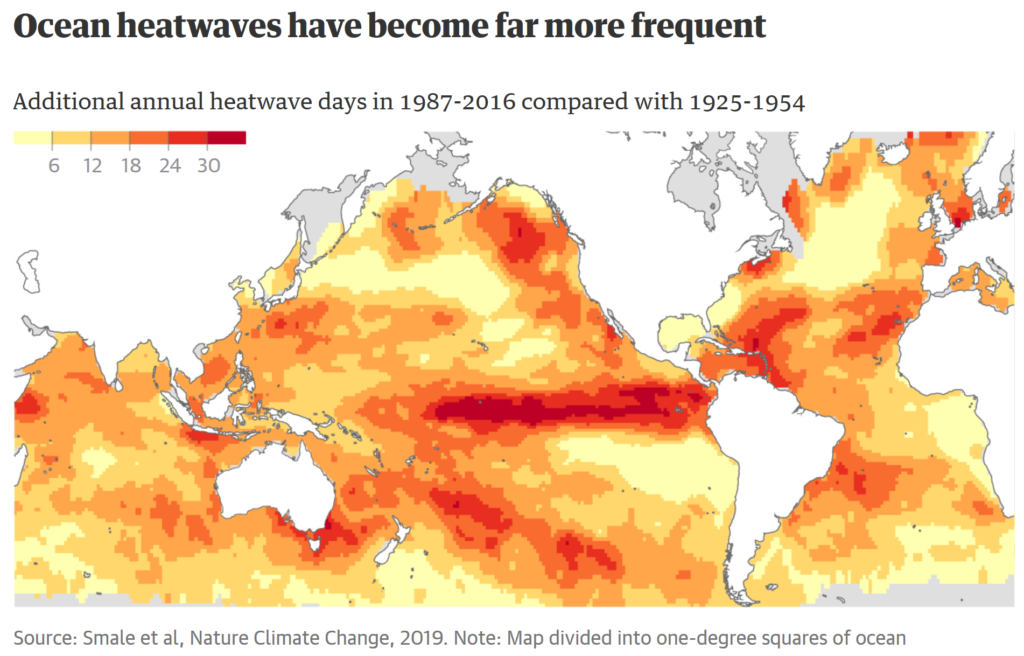

The research found heatwaves are becoming more frequent, prolonged and severe, with the number of heatwave days tripling in the last couple of years studied. In the longer term, the number of heatwave days jumped by more than 50% in the 30 years to 2016, compared with the period of 1925 to 1954.

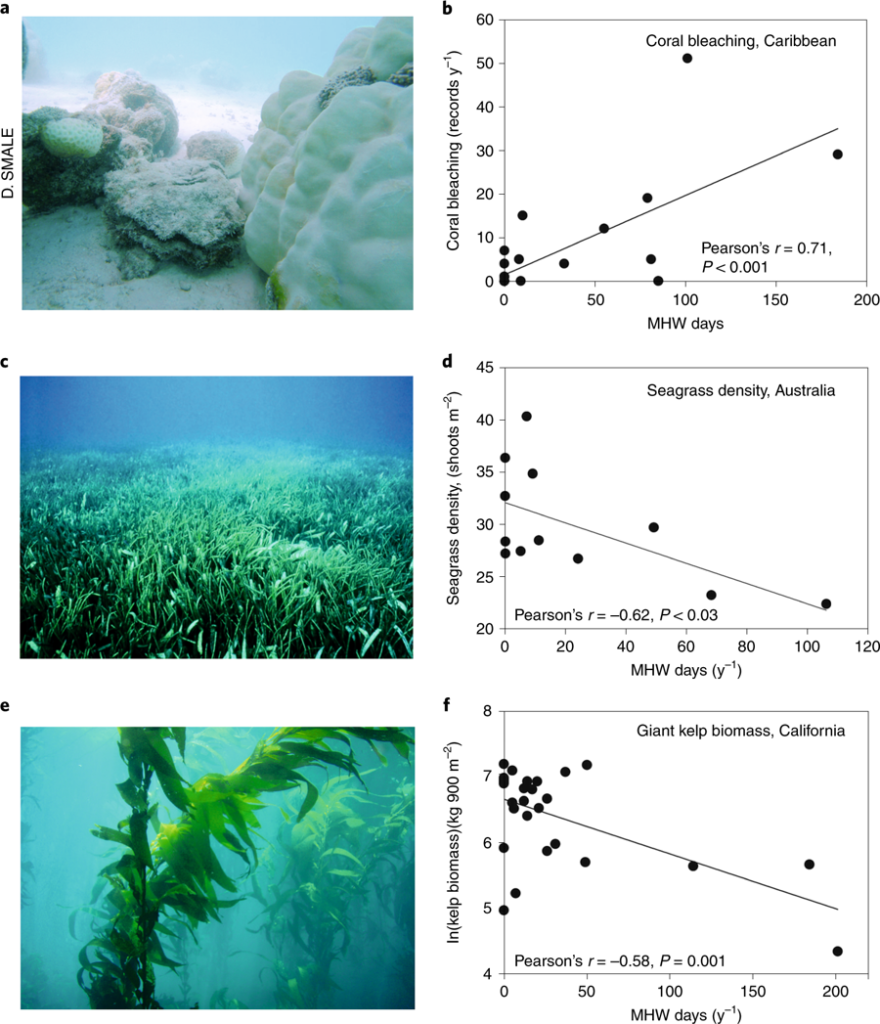

As heatwaves have increased, kelp forests, seagrass meadows and coral reefs have been lost. These foundation species are critical to life in the ocean. They provide shelter and food to many others, but have been hit on coasts from California to Australia to Spain.

“You have heatwave-induced wildfires that take out huge areas of forest, but this is happening underwater as well,” said Dan Smale at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, UK, who led the research published in Nature Climate Change. “You see the kelp and seagrasses dying in front of you. Within weeks or months they are just gone, along hundreds of kilometres of coastline.” [more]

Heatwaves sweeping oceans ‘like wildfires’, scientists reveal

4 March 2019 (Aberystwyth University) — As the UK reflects on record February temperatures, scientists at Aberystwyth University are reporting a significant increase in heatwaves at sea – with potentially detrimental consequences for marine life.

Writing in the journal Nature Climate Change, Dr Pippa Moore from the Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences and colleagues from seven different countries report a 54% increase in ‘Marine Heatwaves’ between 1987 and 2016 compared with the period 1925 to 1954.

Similar to heatwaves on land, marine heatwaves occur when unusually warm weather persists for prolonged periods of time at sea, but their impacts on marine species and ecosystems are poorly understood.

Led by Dr Dan Smale of the Marine Biological Association (UK), this is the first study to assess the biological impacts of several prominent global marine heatwaves.

While they vary in their intensity, size and duration, they all affect critical animal and plant species including corals, seagrasses and kelps.

Marine heatwaves also alter the structure and function of marine communities and have had major implications for human livelihoods through impacts on fisheries.

The study reports some regions to be particularly vulnerable to marine heatwave intensification.

These include the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans due to the co-existence of high levels of biodiversity, a prevalence of species found at their warm water range limits, and/or being subject to additional non-climate human impacts.

Lead author Dr Dan Smale said: “Marine ecosystems currently face a number of threats, including overfishing, ocean acidification and plastic pollution, but periods of extreme temperatures can cause rapid and profound ecological changes, leading to loss of habitat, local extinctions, reduced fisheries catches and altered food webs.”

Dr Pippa Moore from Aberystwyth University and a co-author on the paper said: “Marine heatwaves have for a long time been hidden in comparison to heatwaves on land. The recent terrestrial heatwave in the UK, with the hottest ever recorded winter temperatures, has resulted in many plants and animals becoming active months ahead of normal. When the heatwave ends and normal February/March weather conditions return, it is likely that these early arrivals will be negatively impacted and many might die. The same happens in the sea with marine heatwaves causing widespread mortalities.”

The authors conclude that climate change will continue to increase the frequency of marine heatwaves and the associated impacts on marine biology could have broad reaching effects on ecosystems and the services they provide.

Contact

- Dr Pippa Moore, IBERS, Aberystwyth University, 01970 622293, pim2@aber.ac.uk

- Arthur Dafis, Communications and Public Affairs, Aberystwyth University, 01970 621763, 07841979452, aid@aber.ac.uk

Heatwaves at sea are more frequent and threaten biodiversity, study suggests

ABSTRACT: The global ocean has warmed substantially over the past century, with far-reaching implications for marine ecosystems1. Concurrent with long-term persistent warming, discrete periods of extreme regional ocean warming (marine heatwaves, MHWs) have increased in frequency2. Here we quantify trends and attributes of MHWs across all ocean basins and examine their biological impacts from species to ecosystems. Multiple regions in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans are particularly vulnerable to MHW intensification, due to the co-existence of high levels of biodiversity, a prevalence of species found at their warm range edges or concurrent non-climatic human impacts. The physical attributes of prominent MHWs varied considerably, but all had deleterious impacts across a range of biological processes and taxa, including critical foundation species (corals, seagrasses, and kelps). MHWs, which will probably intensify with anthropogenic climate change3, are rapidly emerging as forceful agents of disturbance with the capacity to restructure entire ecosystems and disrupt the provision of ecological goods and services in coming decades.

Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services