Direct killing by humans pushing Earth’s biggest animals toward extinction – “70% of megafauna species are decreasing and 59% are threatened with extinction”

By Steve Lundeberg

30 January 2019

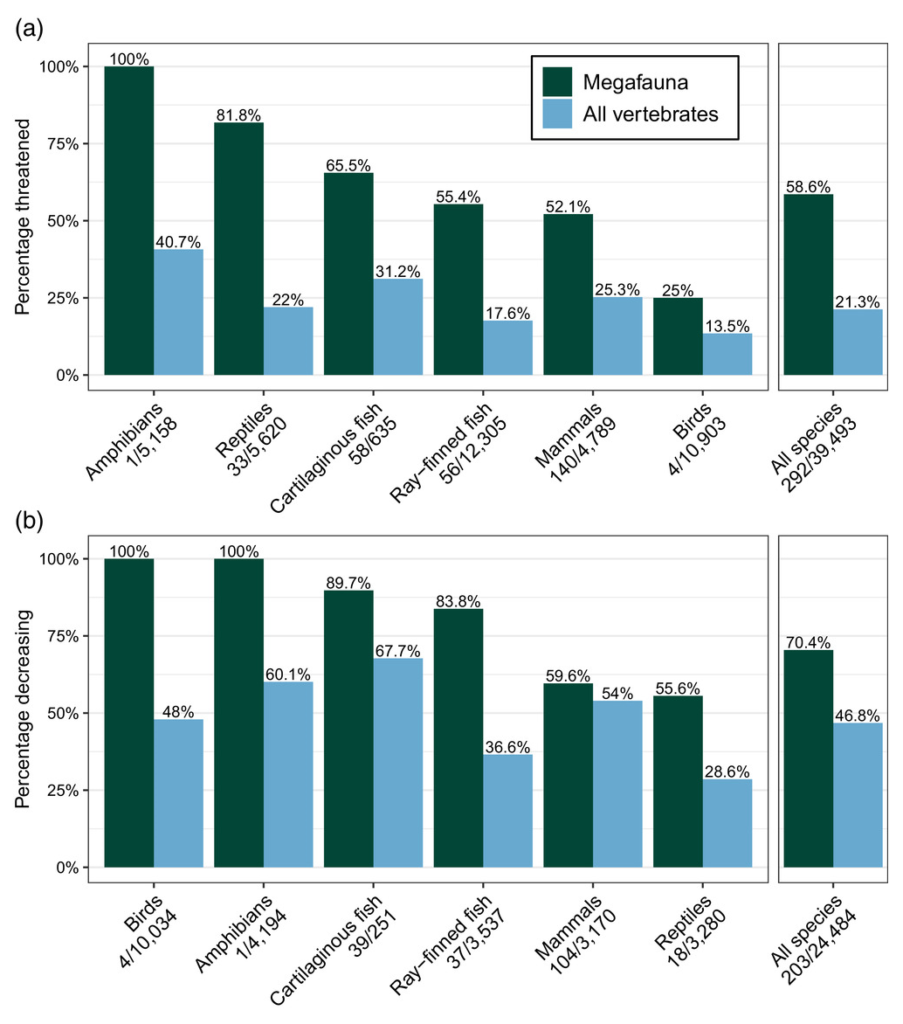

CORVALLIS, Oregon (OSU) – One hundred forty-three species of large animals are decreasing in number and 171 are under threat of extinction, according to new research that suggests humans’ meat consumption habits are primarily to blame.

Findings published today in Conservation Letters involved an analysis of 292 species of “megafauna” – species that are unusually large in comparison to other species in the same class.

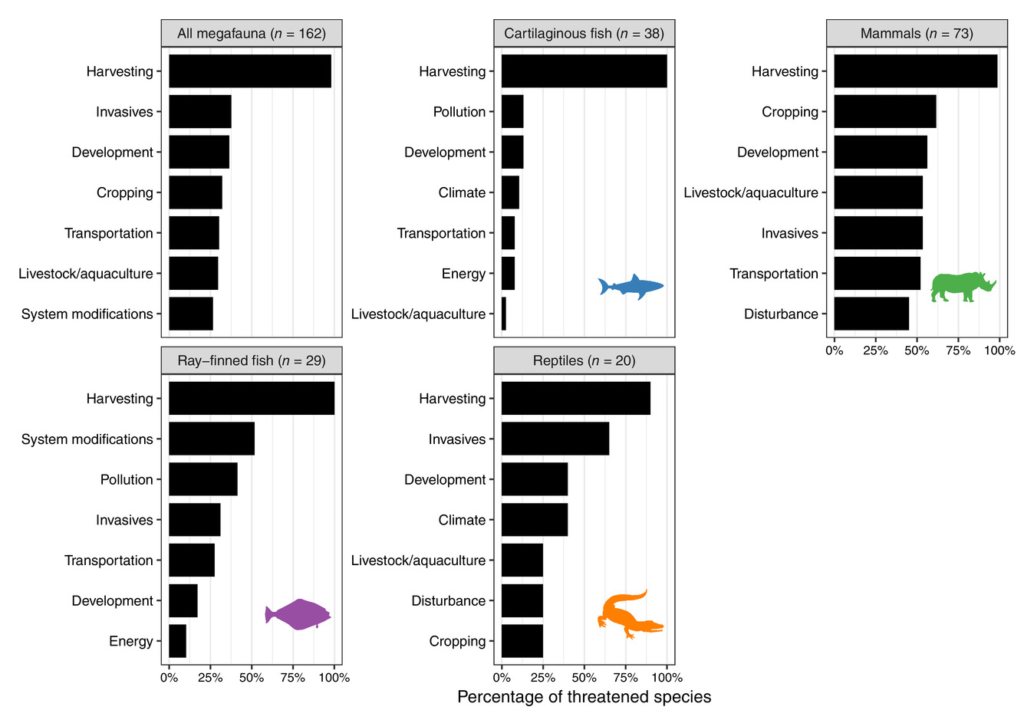

“Direct harvest for human consumption of meat or body parts is the biggest danger to nearly all of the large species with threat data available,” said the study’s corresponding author, William Ripple, distinguished professor of ecology in the Oregon State University College of Forestry. “Thus, minimizing the direct killing of these vertebrate animals is an important conservation tactic that might save many of these iconic species as well as all of the contributions they make to their ecosystems.”

Ripple and colleagues in the College of Forestry were part of an international collaboration that built a list of megafauna based on body size and taxonomy.

The mass thresholds the researchers decided on were 100 kilograms (220 pounds) for mammals, ray-finned fish and cartilaginous fish and 40 kilograms (88 pounds) for amphibians, birds and reptiles since species within these classes are generally smaller.

“Those new thresholds extended the number and diversity of species included as megafauna, allowing for a broader analysis of the status and ecological effects of the world’s largest vertebrate animals,” Ripple said. “Megafauna species are more threatened and have a higher percentage of decreasing populations than all the rest of the vertebrate species together.”

Over the past 500 years, as humans’ ability to kill wildlife at a safe distance has become highly refined, 2 percent of megafauna species have gone extinct. For all sizes of vertebrates, the figure is 0.8 percent.

“Our results suggest we’re in the process of eating megafauna to extinction,” Ripple said. “Through the consumption of various body parts, users of Asian traditional medicine also exert heavy tolls on the largest species. In the future, most megafauna species are likely to experience further population declines and could become extinct or very rare.”

Nine megafauna species have either gone extinct overall, or gone extinct in all wild habitats, in the past 250 years, including two species of giant tortoise, one of which disappeared in 2012, and two species of deer.

“In addition to intentional harvesting, a lot of land animals get accidentally caught in snares and traps, and the same is true of gillnets, trawls and longlines in aquatic systems,” Ripple said. “And there’s also habitat degradation to contend with. When taken together, these threats can have major negative cumulative effects on vertebrate species.”

Among those threatened is the Chinese giant salamander, which can grow up to 6 feet long and is one of only three living species in an amphibian family that traces back 170 million years. Considered a delicacy in Asia, it’s under siege by hunting, development and pollution, and its extinction in the wild is now imminent.

“Preserving the remaining megafauna is going to be difficult and complicated,” Ripple said. “There will be economic arguments against it, as well as cultural and social obstacles. But if we don’t consider, critique and adjust our behaviors, our heightened abilities as hunters may lead us to consume much of the last of the Earth’s megafauna.”

Collaborators included Christopher Wolf, Thomas Newsome and Matthew Betts of the College of Forestry, as well as researchers at the University of California Los Angeles and in Australia, Canada, Mexico and France.

Direct killing by humans pushing Earth’s biggest fauna toward extinction

ABSTRACT: Many of the world’s vertebrates have experienced large population and geographic range declines due to anthropogenic threats that put them at risk of extinction. The largest vertebrates, defined as megafauna, are especially vulnerable. We analyzed how human activities are impacting the conservation status of megafauna within six classes: mammals, ray‐finned fish, cartilaginous fish, amphibians, birds, and reptiles. We identified a total of 362 extant megafauna species. We found that 70% of megafauna species with sufficient information are decreasing and 59% are threatened with extinction. Surprisingly, direct harvesting of megafauna for human consumption of meat or body parts is the largest individual threat to each of the classes examined, and a threat for 98% (159/162) of threatened species with threat data available. Therefore, minimizing the direct killing of the world’s largest vertebrates is a priority conservation strategy that might save many of these iconic species and the functions and services they provide.