Hunting accounts for massive declines in tropical animal populations

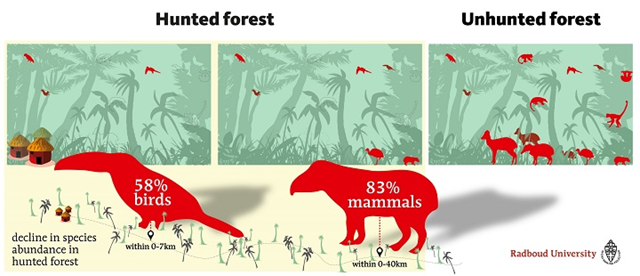

13 April 2017 (Radboud University) – Hunting is a major threat to wildlife particularly in tropical regions, but a systematic large-scale estimate of hunting-induced declines of animal numbers was lacking so far. A study published in Science on April 14 fills this gap. An international team of ecologists and environmental scientists found that bird populations declined on average by 58 percent and mammal populations by 83 within 7 and 40 km of hunters’ access points, such as roads and settlements. Additionally, the team found that commercial hunting had a higher impact than hunting for family food, and that hunting pressure was higher in areas with better accessibility to major towns where wild meat could be traded. The impact of hunting was found to be larger than the team expected. “Thanks to this study, we know that only 17 percent of the original mammal abundance and 42 percent of the birds remain in hunted areas.” The researchers synthesised 176 studies to quantify hunting-induced declines of mammal and bird populations across the tropics of Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. The study was led by Ana Benítez-López, who works at the department of Environmental Science at Radboud University in Nijmegen. She cooperated with researchers from the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL), the universities of Wageningen and Utrecht in the Netherlands and a colleague from the School of Life Sciences, University of Sussex.

Higher hunting pressure around villages and roads

“There are several drivers of animal decline in tropical landscapes: habitat destruction, overhunting, fragmentation, et cetera. While deforestation and habitat loss can be monitored using remote sensing, hunting can only be tracked on the ground. We wanted to find a systematic and consistent way to estimate the impact of hunting across the tropics. As a starting point, we used the hypothesis that humans gather resources in a circle around their village and in the proximity of roads. As such, hunting pressure is higher in the proximity of villages and other access points. From there the densities of species increase up to a distance where no effect of hunting is observed. We called this species depletion distances which we quantified in our analysis. This will allow us to map hunting-induced declines across the tropics for the first time,” Benítez-López explains.

Not only the big cuddly species

The main novelty of the current study is that it combined the evidence across many local studies, thus for the first time providing an overarching picture of the magnitude of the impact across a large number of species. The study takes all animals into account – not only the big cuddly species, but birds and rodents as well. Benítez-López explains the difference in impact between birds and mammals: “Mammals are more sought after because they’re bigger and provide more food. They are worth a longer trip. The bigger the mammal, the further a hunter would walk to catch it.” With increasing wild meat demand for rural and urban supply, hunters have harvested the larger species almost to extinction in the proximity of the villages and they must travel further distances to hunt. Besides, for commercially interesting species such as elephants and gorillas, hunting distances are much larger because the returns are higher.

Protected areas are no safe haven

Another interesting finding of this study is that mammal populations have also been reduced by hunting even within protected areas. “Strategies to sustainably manage wild meat hunting in both protected and unprotected tropical ecosystems are urgently needed to avoid further defaunation,” she says. “This includes monitoring hunting activities by increasing anti-poaching patrols and controlling overexploitation via law enforcement.” Benítez-López e.a. The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science, April 14 2017 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaj1891

Contact

- Ana Benítez López; Environmental Science

- a.benitez@science.ru.nl; + 31 24-3653291; +31 626637709

- Dr A. Benítez-López speaks English and Spanish. Prof. Mark Huijbregts is available for Dutch interviews. m.huijbregts@science.ru.nl; +31 24-3652835

- Highres version of infografic

Hunting accounts for massive declines in tropical animal populations

ABSTRACT: Hunting is a major driver of biodiversity loss, but a systematic large-scale estimate of hunting-induced defaunation is lacking. We synthesized 176 studies to quantify hunting-induced declines of mammal and bird populations across the tropics. Bird and mammal abundances declined by 58% (25 to 76%) and by 83% (72 to 90%) in hunted compared with unhunted areas. Bird and mammal populations were depleted within 7 and 40 kilometers from hunters’ access points (roads and settlements). Additionally, hunting pressure was higher in areas with better accessibility to major towns where wild meat could be traded. Mammal population densities were lower outside protected areas, particularly because of commercial hunting. Strategies to sustainably manage wild meat hunting in both protected and unprotected tropical ecosystems are urgently needed to avoid further defaunation.

The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations