EPA concludes fracking can threaten water supplies

[Expect these sorts of studies to stop when Scott Pruitt, longtime enemy of the EPA and Trump’s selection to head the EPA, takes control. –Des] By Patrick G. Lee

14 December 2016 (ProPublica) – Starting in 2008, ProPublica published stories that found hydraulic fracking had damaged drinking water supplies across the country. The reporting examined how fracking in some cases had dislodged methane, which then seeped into water supplies. In other instances, the reporting showed that chemicals related to oil and gas production through fracking were winding up in drinking water, and that waste water resulting from fracking operations was contaminating water sources. Many environmentalists hailed the reporting. The gas drilling industry, for its part, pushed back, initially dismissing the accounts as anecdotal at best. This week, the Environmental Protection Agency issued its latest and most thorough report on fracking’s threat to drinking water, and its findings support ProPublica’s reporting. The EPA report found evidence that fracking has contributed to drinking water contamination — “cases of impact” — in all stages of the process: water withdrawals for hydraulic fracturing; spills during the management of hydraulic fracturing fluids and chemicals; injection of hydraulic fracturing fluids directly into groundwater resources; discharge of inadequately treated hydraulic fracturing wastewater to surface water resources; and disposal or storage of hydraulic fracturing wastewater in unlined pits, resulting in contamination of groundwater resources. In an interview, Amy Mall, a senior policy analyst at the National Resources Defense Council, said the EPA’s report was welcome. “Many of us have been working on this issue for many years, and industry has repeatedly said that there is no evidence that fracking has contaminated drinking water,” Mall said. The EPA report comes a year after its initial set of findings set off fierce criticism by environmental advocates and health professionals. That report, issued in 2015, said the agency had found no evidence that fracking had “led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources.” Many accused the agency of pulling its punches and adding to confusion among the public. News organizations throughout the U.S. interpreted the EPA’s language to mean it had concluded fracking did not pose a threat to water supplies and public health. The EPA said in its report this week that the sentence about the lack of evidence of systemic issues had been intentionally removed because the agency’s scientists had “concluded it could not be quantitatively supported.” “I think one of the concerns about the original document was that the EPA seemed to say that everything was fine,” said Rob Jackson, a professor of earth-system science at Stanford University. “It’s important that we understand the ways and the cases where things have gone wrong, to keep them from happening elsewhere.” The EPA’s latest declaration comes as a Trump administration apparently hostile to almost any kind of regulation of fracking prepares to assume office. But those worried about fracking’s implications for the environment have long been discouraged by the lack of consistent and stringent state or federal regulation. “Because state regulators have not fully investigated cases of drinking water contamination, and because federal regulators have been handcuffed by Congress into how much they can regulate, the science wasn’t as robust as it should have been,” said Mall, the analyst at NRDC. “It’s a pattern of, the rules are too weak, and the ones that are on the books aren’t enforced enough.” The more significant impact of a Trump administration, however, may be in limiting the EPA’s appetite for aggressive and continued study. The report issued this week was six years in the making, but made clear there was still much work to be done to better and more comprehensively determine fracking’s impact on the environment, chiefly water supplies. “It was not possible to calculate or estimate the national frequency of impacts on drinking water resources from activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle or fully characterize the severity of impacts,” the report said. The Trump administration’s transition team did not immediately respond to an e-mailed request for comment about its position on fracking and the EPA’s final report. Trump’s transition website promises to “unleash an energy revolution” and “streamline the permitting process for all energy projects.” It also says it will “refocus the EPA on its core mission of ensuring clean air, and clean, safe drinking water for all Americans.” Advocates for hydraulic fracturing argue that the final EPA report is not vastly different from the draft version. “Anecdotal evidence about localized impacts does not disprove the central thesis, which is that there is no evidence of widespread or systemic impacts,” said Scott Segal, a partner at Bracewell LLP who represents oil and gas developers. “There’s a lot of exaggeration. There’s a lot of mischaracterization of the extent of contamination that’s based on a desire to enhance recovery in tort liability lawsuits.” [more]

EPA Concludes Fracking a Threat to U.S. Water Supplies

Executive Summary

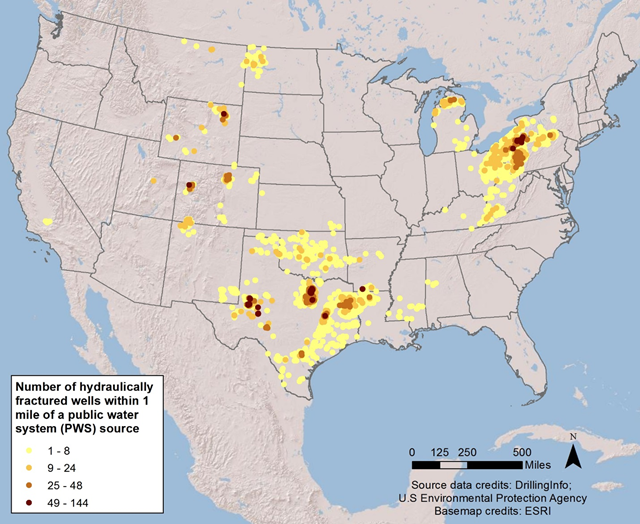

People rely on clean and plentiful water resources to meet their basic needs, including drinking, bathing, and cooking. In the early 2000s, members of the public began to raise concerns about potential impacts on their drinking water from hydraulic fracturing at nearby oil and gas production wells. In response to these concerns, Congress urged the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to study the relationship between hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas and drinking water in the United States. The goals of the study were to assess the potential for activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle to impact the quality or quantity of drinking water resources and to identify factors that affect the frequency or severity of those impacts. To achieve these goals, the EPA conducted independent research, engaged stakeholders through technical workshops and roundtables, and reviewed approximately 1,200 cited sources of data and information. The data and information gathered through these efforts served as the basis for this report, which represents the culmination of the EPA’s study of the potential impacts of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas on drinking water resources. The hydraulic fracturing water cycle describes the use of water in hydraulic fracturing, from water withdrawals to make hydraulic fracturing fluids, through the mixing and injection of hydraulic fracturing fluids in oil and gas production wells, to the collection and disposal or reuse of produced water. These activities can impact drinking water resources under some circumstances. Impacts can range in frequency and severity, depending on the combination of hydraulic fracturing water cycle activities and local- or regional-scale factors. The following combinations of activities and factors are more likely than others to result in more frequent or more severe impacts:

- Water withdrawals for hydraulic fracturing in times or areas of low water availability, particularly in areas with limited or declining groundwater resources;

- Spills during the management of hydraulic fracturing fluids and chemicals or produced water that result in large volumes or high concentrations of chemicals reaching groundwater resources;

- Injection of hydraulic fracturing fluids into wells with inadequate mechanical integrity,

allowing gases or liquids to move to groundwater resources;- Injection of hydraulic fracturing fluids directly into groundwater resources;

- Discharge of inadequately treated hydraulic fracturing wastewater to surface water resources; and

- Disposal or storage of hydraulic fracturing wastewater in unlined pits, resulting in contamination of groundwater resources.

The above conclusions are based on cases of identified impacts and other data, information, and analyses presented in this report. Cases of impacts were identified for all stages of the hydraulic fracturing water cycle. Identified impacts generally occurred near hydraulically fractured oil and gas production wells and ranged in severity, from temporary changes in water quality to contamination that made private drinking water wells unusable. The available data and information allowed us to qualitatively describe factors that affect the frequency or severity of impacts at the local level. However, significant data gaps and uncertainties in the available data prevented us from calculating or estimating the national frequency of impacts on drinking water resources from activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle. The data gaps and uncertainties described in this report also precluded a full characterization of the severity of impacts. The scientific information in this report can help inform decisions by federal, state, tribal, and local officials; industry; and communities. In the short-term, attention could be focused on the combinations of activities and factors outlined above. In the longer-term, attention could be focused on reducing the data gaps and uncertainties identified in this report. Through these efforts, current and future drinking water resources can be better protected in areas where hydraulic fracturing is occurring or being considered.