New solutions needed to tackle mounting sovereign debt crisis – UN trade and development agency

26 October 2016 (UN) – Prior to a meeting today at the United Nations on sovereign debt restructuring, the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) announced that in order to deal with sovereign debt crises – which are creating a growing threat to economic stability in many developing countries – the world is in need of new ways to tackle the problem. Such crises are an obstacle to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Countries in Africa and elsewhere have been accruing debt while their ability to repay shrinks. Falling commodity prices, a rising dollar, and the prospect of higher interest payments are making repayment even less likely. “Sovereign nations do not have the protection of bankruptcy laws to restructure or delay their debt repayments in the same way that private debtors do,” said UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi in a news release issued ahead of the meeting. He warned that “while creditors cannot easily seize non-commercial public assets, sovereign debt faults bring major problems in terms of reputation and access to further loans.” In the past, debt crises have led to highly speculative funds run by non-cooperative or hold-out bankers, including by “vulture funds,” which aggressively pursue debt repayments, rendering them expensive and potentially disruptive. Since 2000, hedge funds have been the primary plaintiffs in 75 per cent of all litigation cases against sovereign debts. New research will be published next month in a report, indicating that the latest round of borrowing dates to 2006, when the Seychelles issued a sovereign bond, making it the first sub-Saharan African country to do so in the past 30 years, with the exception of South Africa. In the subsequent decade, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, and Zambia have accrued more than $25 billion in bonds, with a principal amount of more than $35 billion. The report’s researchers, Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven and Aleksandr V. Gevorkyan, say that many African countries are now facing repayment difficulties, pointing to Ghana as an example. “Ghana is in a difficult, yet unfortunately common position, as it depends on commodity exports such as gold, oil and cocoa,” they said. “With falling commodity prices, the country faces a decline in revenue and a growing current account deficit,” they added, pointing out that Ghana’s total debt, both external and domestic, is more than 55 per cent of its gross domestic product. Last year, after research contributed by UNCTAD, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution stating that sovereign debt restructuring processes should be guided by basic international principles of law such as sovereignty, good faith, transparency, legitimacy, equitable treatment and sustainability. The resolution reflected a growing concern about renewed sovereign debt crises and long-term debt sustainability in the context of continued global economic fragility.

New solutions needed to tackle mounting sovereign debt crisis – UN trade and development agency

By Aleksandr Gevorkyan and Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven

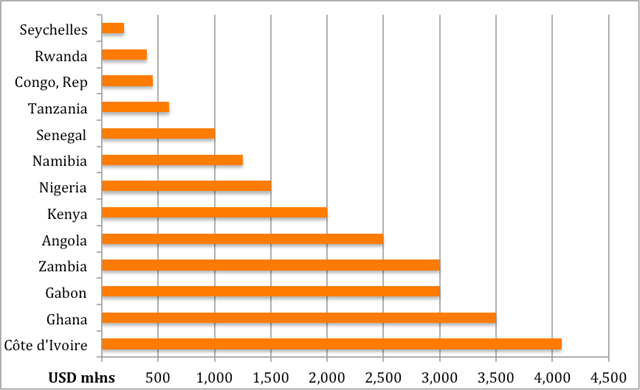

10 October 2016 (Interfima) – In the mid-2000s, 30 African countries received substantial debt reduction through the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Heavily-Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative. Only a decade later, many of the same countries are again facing debt distress. The African Development Bank recently warned its members of the dangers of rising debt obligations, while the IMF has called for an “urgent need to reset” the region’s growth policies. In our new paper titled “Assessing Recent Determinants of Borrowing Costs in Sub-Saharan Africa” in the November 2016 issue of the Review of Development Economics, we trace the latest round of borrowing back to 2006 with Seychelles as the first sub-Saharan African (SSA) country to issue a sovereign bond, with the exception of South Africa, in 30 years. Since then, DR Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Angola, Nigeria, Tanzania, Namibia, Rwanda, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Zambia have all followed suit, accumulating over $25 billion worth of bonds, with a principal amount of more than $35 billion (see Figure 1 for totals by country). As global investors search for yield, they are increasingly looking into emerging markets that borrow in foreign currencies (though few have been able to issue local currency denominated bonds). Barry Eichengreen has long argued, that the extent to which debt is foreign currency denominated, eventually becomes a key determinant of stability in output, capital flows, and exchange rate. For emerging markets such dynamic further exacerbates typical underdevelopment scenarios. Similarly, Michael Pettis argues that the flow of international loans has been driven primarily by external events and not by domestic politics in developing countries since the 1820s. In that analysis, the flows of capital between rich and poor countries are generally determined by domestic conditions in rich countries, rather than the quality of investment opportunities in poor ones. Recently, Gevorkyan, and Canuto (here and here) have called attention to massive capital movements in and out of emerging markets and subsequent effects on macroeconomic development. The contradicting scenarios of financial deepening versus severe macroeconomic destabilization across smaller emerging economies are all too real. The new norm is about low growth rates, continuous leveraging of global liquidity aided by low interest rates, and propensity to volatility in global markets. […] As our paper predicts, many African countries are now facing repayment difficulties. Just two years after the Republic of Congo’s first bond issuance in 2007, Congolese bonds were trading for 20 cents on the dollar, pushing the yield to a record high. Seychelles received an IMF bailout at the height of the financial crisis in late 2008, and still has a soaring debt-to-GDP ratio. Last year, Ghana had to enter an IMF bailout program with a range of austerity conditions. Ghana is in a difficult, yet unfortunately common, position as it depends on commodity exports such as gold, oil and cocoa, so with falling commodity prices, the country faces a decline in revenue and a growing current account deficit. Ghana’s total debt, both external and domestic, is not at more than 55% of its GDP. [more]

The Trouble with Sub-Saharan African Debt

ABSTRACT: This study explores macroeconomic implications of the sovereign bond rush that has been taking place in sub-Saharan Africa since 2006. The focus is on the sub-Saharan sovereign bond yields as proxies for the region’s ability to raise new funds on international markets. Despite the subcontinent’s tour-de-force entrance to the international bond market, this paper reveals that recent (since early 2000s) borrowing in foreign currency is not without macroeconomic risk. Empirically this paper finds that sovereign bond yields are significantly influenced by global volatility, commodity prices and global liquidity—all factors that are out of the control of the sub-Saharan economies in question. These findings suggest that portfolio repositioning by institutional investors prompted by improved growth prospects and implicit monetary policy tightening in the advanced economies or heightened risk perceptions, are likely to result in increased borrowing costs for the sub-Saharan bond issuers and affect their ability to raise funds in international markets. Furthermore, a change in borrowing costs might lead to higher debt-service costs and policy uncertainty, which in turn could lead to suboptimal investment levels and, ultimately, hinder economic development.

Assessing Recent Determinants of Borrowing Costs in Sub-Saharan Africa