Heat waves, productivity, and the urban economy: What are the costs?

29 July 2016 (LSE) – Increasingly hot summers can have devastating effects on worker productivity. As temperatures increase, workers feel decreased energy, loss of concentration, muscle cramps, heat rash, and in extreme cases heat exhaustion or heatstroke. Cities are especially prone to such productivity loses. First, cities tend to be warmer than surrounding areas. This is due to factors like the extensive use of concrete and asphalt, use of equipment such as air conditioning, and lack of shade-bearing vegetation. Second, cities concentrate people, infrastructure, and productive activity. So disruptions to the regular working of the economy have large effects. Productivity losses already occur to different degrees across the world, but this is likely to be exacerbated by climate change. In the absence of measures for climate adaptation, productivity losses will have major impacts upon urban economies. If city policy makers are to implement measures to adapt to heat waves and other climate-related hazards, a better understanding of the scale of damages and the usefulness of different adaptation strategies is required.

Measuring the productivity costs of heat

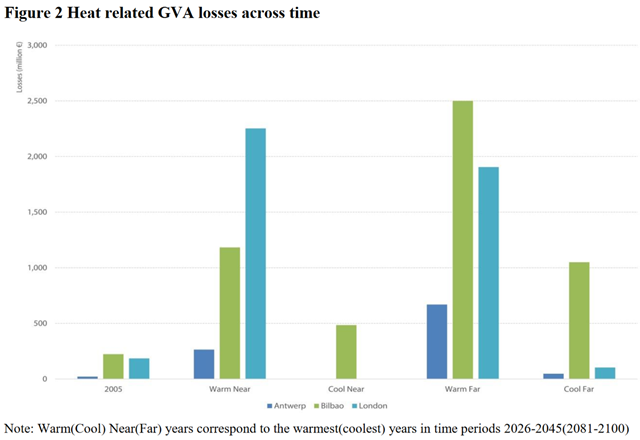

In our recent study, developed as part of the RAMSES (PDF) project, we work to bridge this gap in understanding. We develop a cost methodology that allows researchers and policy makers to assess the costs of heat stress for an urban economy through reduced labour productivity. We also examine the effectiveness of several adaptation measures. In order to measure physiological heat stress, we use Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), which accounts for temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation. We estimate outdoor and indoor WBGT in three case study cities: Antwerp, Bilbao, and London, based on the RPC8.5 scenario for the reference year 2005 and the periods 2026-2045 and 2081-2100. Depending on the energy intensity necessary for different activities, we estimate hourly productivity loss functions for individual workers based on ISO (International Organization for Standardization) standards for recommended hourly work rates at different levels WBGT. These functions are then attributed to different sectors of the metropolitan economy depending on the energy levels needed by workers to perform different activities. Sectoral production functions that embed these productivity losses are then aggregated to annual Gross Value Added (GVA) – a commonly used measure of the value of goods and services produced in an economy. Precisely how the value of production varies with WBGT depends both on the weight of each sector within the city economy and on the exposure of each sector to heat stress. We find that, in the future, costs to London’s economy in warm years could amount to between 1.9 billion euros and 2.3 billion euros, which represents over 0.4% of 2005 city GVA. This suggests costs could rise to a similar level to those currently occurring in Australia. We estimate losses in the reference year 2005 of around 185 million euros. This means that current temperature costs of heat stress to the urban economy are already substantial.

What adaptation? The London “siesta”

We use the same method to estimate how effective alternative adaptation measures are at averting these losses. Our analysis suggests a change in working hours is a potentially important adaptation measure for the case of London. In particular, working schedules that avoid early afternoon work, such as working from 07:00-11:00 and 17:00-20:00 instead of 09:00-13:00 and 14:00-17:00 – the equivalent to the Spanish “siesta” – could save the London economy over 700 million euros by the end of the century. Air conditioning, increased ventilation and solar blinds all have large cost-saving potential. But unlike air conditioning, changing working hours does not compromise efforts to reduce emissions. It additionally protects both indoor and outdoor work, providing benefits for cities with large construction sectors, like London.

A call for adaptation

19th July 2016 was the hottest day of the year so far in London, with temperatures over 30oC. This sparked a wave of immediate health problems and transport disruptions, as speed limits were introduced to prevent rail buckling. There were also media reports of increased violence. Our study suggests additional costs due to productivity losses may also be substantial. This is all the more troubling when we consider that climate change means temperatures like the ones of 19th July will become more and more common. It is therefore vital that policy makers understand how heat affects productivity in different urban contexts and what adaptation measures work better.

Heat waves, productivity, and the urban economy: What are the costs?