Vanishing Act: Why insects are declining and why it matters – ‘The decline is dramatic and depressing and it affects all kinds of insects, including butterflies, wild bees, and hoverflies’

By Christian Schwägerl

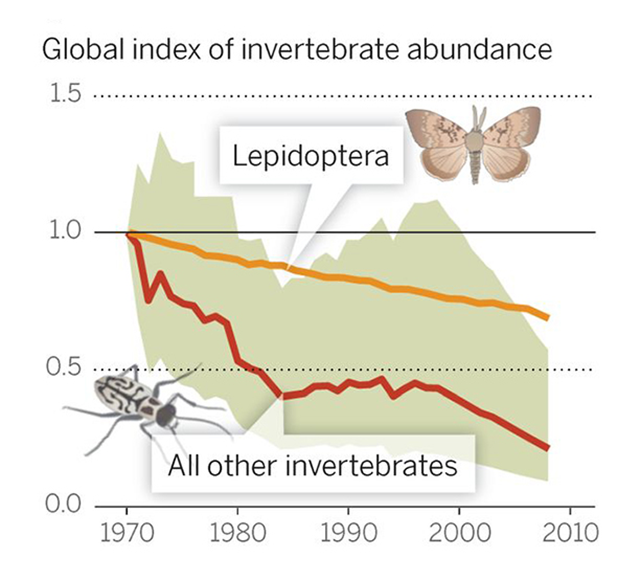

6 July 2016 (e360) – Every spring since 1989, entomologists have set up tents in the meadows and woodlands of the Orbroicher Bruch nature reserve and 87 other areas in the western German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The tents act as insect traps and enable the scientists to calculate how many bugs live in an area over a full summer period. Recently, researchers presented the results of their work to parliamentarians from the German Bundestag, and the findings were alarming: The average biomass of insects caught between May and October has steadily decreased from 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds) per trap in 1989 to just 300 grams (10.6 ounces) in 2014. “The decline is dramatic and depressing and it affects all kinds of insects, including butterflies, wild bees, and hoverflies,” says Martin Sorg, an entomologist from the Krefeld Entomological Association involved in running the monitoring project. Another recent study has added to this concern. Scientists from the Technical University of Munich and the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt have determined that in a nature reserve near the Bavarian city of Regensburg, the number of recorded butterfly and Burnet moth species has declined from 117 in 1840 to 71 in 2013. “Our study reveals, through one detailed example, that even official protection status can’t really prevent dramatic species loss,” says Thomas Schmitt, director of the Senckenberg Entomological Institute. Declines in insect populations are hardly limited to Germany. A 2014 study in Science documented a steep drop in insect and invertebrate populations worldwide. By combining data from the few comprehensive studies that exist, lead author Rodolfo Dirzo, an ecologist at Stanford University, developed a global index for invertebrate abundance that showed a 45 percent decline over the last four decades. Dirzo points out that out of 3,623 terrestrial invertebrate species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature [IUCN] Red List, 42 percent are classified as threatened with extinction. “Although invertebrates are the least well-evaluated faunal groups within the IUCN database, the available information suggests a dire situation in many parts of the world,” says Dirzo. A major survey of threats to insect life by the Zoological Society of London, published in 2012, concluded that many insect populations worldwide are in severe decline, limiting food supplies for larger animals and affecting ecosystem services like pollination. In Europe and the United States, researchers have documented declines in wild and managed bee populations of 30 to 40 percent and more due to so-called colony collapse disorder. Other insect species, such as the monarch butterfly, also have experienced sharp declines. Jürgen Deckert, insect custodian at the Berlin Natural History Museum, says he is worried that “the decline in insect populations is gradual and that there’s a risk we will only really take notice once it is too late.” Scientists cite many factors in the fall-off of the world’s insect populations, but chief among them are the ubiquitous use of pesticides, the spread of monoculture crops such as corn and soybeans, urbanization, and habitat destruction. [more]

Vanishing Act: Why Insects Are Declining and Why It Matters

ABSTRACT: Environmental changes strongly impact the distribution of species and subsequently the composition of species assemblages. Although most community ecology studies represent temporal snap shots, long-term observations are rather rare. However, only such time series allow the identification of species composition shifts over several decades or even centuries. We analyzed changes in the species composition of a southeastern German butterfly and burnet moth community over nearly 2 centuries (1840–2013). We classified all species observed over this period according to their ecological tolerance, thereby assessing their degree of habitat specialisation. This classification was based on traits of the butterfly and burnet moth species and on their larval host plants. We collected data on temperature and precipitation for our study area over the same period. The number of species declined substantially from 1840 (117 species) to 2013 (71 species). The proportion of habitat specialists decreased, and most of these are currently endangered. In contrast, the proportion of habitat generalists increased. Species with restricted dispersal behavior and species in need of areas poor in soil nutrients had severe losses. Furthermore, our data indicated a decrease in species composition similarity between different decades over time. These data on species composition changes and the general trends of modifications may reflect effects from climate change and atmospheric nitrogen loads, as indicated by the ecological characteristics of host plant species and local changes in habitat configuration with increasing fragmentation. Our observation of major declines over time of currently threatened and protected species shows the importance of efficient conservation strategies.

"Our study reveals, through one detailed example, that even official protection status can't really prevent dramatic species loss,"

Well, of course not. Laws don't change behavior. In this case, civilization and it's effects. Constant growth means destruction of habitat, greenhouse gasses and always too many people placing too many demands on too few remaining resources. Bugs just don't factor in to this paradigm in the slightest. Yet they are absolutely critical for other species, even us. Without them, we won't survive either.

I'll say it again – POPULATION is a HUGE problem and it's usually just assumed that we can address everything else and this particular problem will resolve itself. Uh no, that isn't how it will work and why it hasn't worked.

Every single human and particularly those in developed countries represents an inordinately large ecological footprint on the biology of this planet. The footprint is the lifestyle, living habits and resource demands and pollution caused. Both population and the demands of the population must go DOWN.

The incessant growth paradigm is considered absolutely sacred, but it is the life of the planet that pays the real price. Extinction is as they say, forever and we simply don't "see it" because we are removed from the living biology that once existed. If a fish goes extinct, a bird, bug, reptile or amphibian – what do we care? Our concerns are only upon ourselves, our wealth and our so-called "future" we envision for ourselves. What is unfolding upon the environment and all the life within it is really of no real concern.

Until it all fails. When critical species are so depleted or driven into extinction that it threatens us too and then FINALLY we gain a tiny bit of awareness but it is much too late. The juggernaut of civilization remains unresolved — and we remain caught in the web of lies and deceits and dependencies, having utterly forgotten what it really means to live on this planet or having the skills to do so.

There can be no doubt whatsoever what this means and where it is all headed. At best, we can report on the demise of species, the impacts of civilization and depredation of the environment, but we can nothing to truly resolve it. Oh, we're trying, but we're failing so incredibly badly that it boggles the mind. We edge ever closer to our own collapse after having destroyed the living biosphere that sustained us for millions of years. The outcome is determined as much as our unwillingness to change is. Either we address civilization itself, population and lifestyles or accept extinction (ours) relatively soon (estimates are as short as a single generation now).

One more time — we cannot live here if they cannot live here. Species extinctions have stupendous impacts upon the entire biosphere and are now occurring at such a break-neck rate that our future survival on this planets is very questionable.

I am closing down everything to get ready to go to bed and i decide to check Desdemona D. before shutting down the computer and what do i see but this very timely subject. I have noticed a decline in the bug population (for one thing, a lot less bugs hitting my car windshield when i had a car). I have noticed this decline, but never heard anyone mention it before. But, i think it is some kind of weird unexplained thing that is wiping them out – very likely having to do with global warming. One example i noticed when i was living in the California high desert at first arrival there were these flying insects that were harmless, but after a few years they all disappeared – didn't even see one of them. I remember insects were quite plentiful, but i have had experience now where i will hardly see any flying around or anywhere. And i noticed a long time ago the decline of insects, but never said anything to anyone and so i am glad to see this article because it helps to confirm my suspicions that something is happening to their population. This is a good article.