Antarctic coastline images reveal four decades of ice loss to ocean – ‘Now we know this has been occurring pervasively along the coastline for almost half a century’

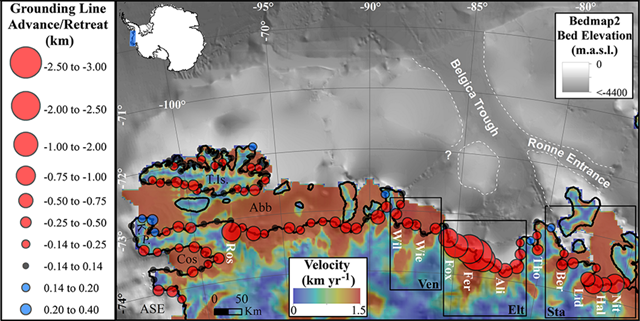

WASHINGTON, DC, 1 June 2016 (AGU) – Part of Antarctica has been losing ice to the ocean for far longer than had been expected, satellite pictures reveal. A study of images along 2000 kilometers (1,240 miles) of West Antarctica’s coastline has shown the loss of about 1000 square kilometers (about 390 square miles) of ice – an area equivalent to the city of Berlin – over the past 40 years. Researchers were surprised to find that the region has been losing ice for such a length of time. Their findings will help improve estimates of global sea level rise caused by ice melt, they said. A research team from the University of Edinburgh analyzed hundreds of satellite photographs of the ice margin captured by NASA, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the European Space Agency (ESA). The study has been accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union. They found that ice has been retreating consistently along almost the entire coastline of Antarctica’s Bellingshausen Sea since satellite records began. “We knew that ice had been retreating from this region recently but now, thanks to a wealth of freely available satellite data, we know this has been occurring pervasively along the coastline for almost half a century,” said Frazer Christie, a PhD student in the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, who co-led the study. The team also monitored ice thickness and thinning rates using data taken from satellites and the air. This showed that some of the largest changes, where ice has rapidly thinned and retreated several miles since 1975, correspond to where the ice front is deepest. Scientists suggest the loss of ice is probably caused by warmer ocean waters reaching Antarctica’s coast, rather than rising air temperatures. They say further satellite monitoring is needed to enable scientists to track progress of the ice sheet. “This study provides important context for our understanding of what is causing ice to retreat around the continent,” said Robert Bingham, reader in Glaciology and Geophysics and a chancellor’s fellow at the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences and a co-author of the study. “We now know change to West Antarctica has been longstanding, and the challenge ahead is to determine what has been causing these ice losses for so long.” Their study was carried out in collaboration with Temple University in Philadelphia. It was supported by the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, the Natural Environment Research Council and the ESA.

Antarctic coastline images reveal four decades of ice loss to ocean

ABSTRACT: Changes to the grounding line, where grounded ice starts to float, can be used as a remotely sensed measure of ice-sheet susceptibility to ocean-forced dynamic thinning. Constraining this susceptibility is vital for predicting Antarctica’s contribution to rising sea levels. We use Landsat imagery to monitor grounding line movement over four decades along the Bellingshausen margin of West Antarctica, an area little monitored despite potential for future ice losses. We show that ~65% of the grounding line retreated from 1990 to 2015, with pervasive and accelerating retreat in regions of fast ice flow and/or thinning ice shelves. Venable Ice Shelf confounds expectations in that, despite extensive thinning, its grounding line has undergone negligible retreat. We present evidence that the ice shelf is currently pinned to a sub-ice topographic high which, if breached, could facilitate ice retreat into a significant inland basin, analogous to nearby Pine Island Glacier.