India coral reefs experiencing widespread bleaching, scientist says

By Shreya Dasgupta

11 May 2016 (mongabay.com) – Coral reefs around the world are in deep trouble. Last month, scientists reported that Australia’s Great Barrier Reef corals were experiencing “the worst mass bleaching event in its history”. Of the 500 coral reefs they observed while flying over 4,000 kilometers (~2,485 miles) of the Great Barrier Reef, only four reefs did not show any sign of bleaching. Terry Hughes, convenor of Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Taskforce, called it the “saddest research trip” of his life. Other scientists have called the underwater sight of widespread bleaching “catastrophic”. In other parts of the world too, similar “catastrophic” scenes are playing out. Off the south-western coast of India, the lesser-known coral reefs of the Lakshadweep Archipelago in the northern Indian Ocean are struggling to survive. A small team of six field biologists from the Nature Conservation Foundation in India, have observed soaring sea surface temperatures and widespread coral bleaching this year. In every reef that the team has surveyed in 2016 so far, corals are turning white or pale. Moreover, the heat stress has already killed many corals in the region, the team said in a statement. Lakshadweep’s corals are not new to bleaching. In 1998 and 2010, similar El Niño events have had calamitous impacts on the reefs. While the Lakshadweep reefs recovered from the 1998 event, recovery following the 2010 event has been slower. And with the ongoing El Niño event, scientists are seriously concerned. […] Mongabay spoke with Arthur about the state of coral reefs in the Lakshadweep Archipelago and their ability to bounce back.

Mongabay: When did you first observe bleaching in Lakshadweep’s coral reefs this year? Rohan Arthur: Well, we have been expecting unusual sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean since 2015 and have been on bleaching watch ever since last winter. Anticipating that this was going to be a cruel summer, we scrambled together a team of researchers in December to travel the archipelago and assess its reefs before our waters started heating up. Already back then we began noticing corals showing clear signs of heat stress: they were turning strange colors and feeding unusually during the day (most healthy coral feed actively only at night). By April, these stressed corals were everywhere. In our most recent surveys in early May, we have not found a single reef that has been spared the effects of the bleaching. Even at deeper, supposedly cooler, and therefore more protected reefs, corals are quickly giving up the ghost. Mongabay: What environmental conditions result in coral reef bleaching in the Lakshadweep? Rohan Arthur: Corals share a tight symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae that produce most of the nutrition that the corals require to survive. These algae live in the soft tissue of the coral polyp, giving corals their radiant colors. This relationship gets easily strained though, and when corals are stressed they respond by expelling their algal partners. This results in corals changing colors, becoming increasingly pale before bleaching completely white as this stress increases. The mass bleaching of coral currently underway in the Lakshadweep is being caused by unusually high sea surface temperatures as the Indian Ocean swelters under particularly unforgiving El Niño conditions. The El Niño is a warm ocean current that spreads across Pacific and into the Indian Ocean when trade winds fail. The increasing intensity and frequency of these unusual events bears the clear fingerprint of human-caused climate change and this year’s El Niño is leaving behind a wave of untold devastation on the reefs of the world.

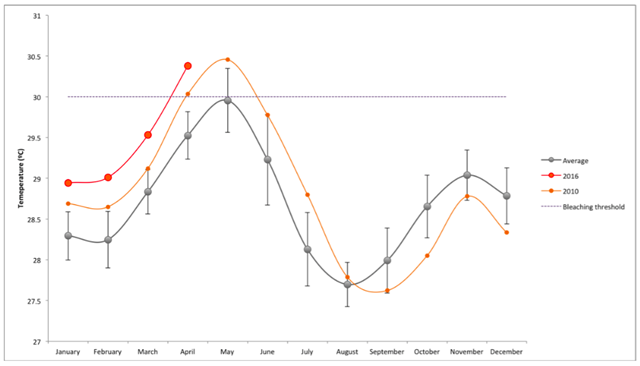

The first few months of 2016 have seen the hottest monthly sea surface temperatures in the Lakshadweep waters since accurate records have been kept. Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) recorded by NOAA’s Virtual Station (based on satellite readings) show average temperatures of around 30 degrees Centigrade (~86 degrees Fahrenheit) for the period between February and May in 2016. This is close to one degree above the average over the last 15 years, which represents a radical increase in SSTs for this year. Individually, we have recorded temperatures as high as 34-35 degrees Centigrade (93-95 degree Fahrenheit) within the first few metres of water — and at these temperatures we have been recording mortalities not merely of coral but of coral reef fish as well. The Lakshadweep is only one of many reef regions that will potentially succumb to this event. It will be several months before we can properly assess the full scale of the damage it has wreaked. [more]

‘Heart wrenching’: India’s coral reefs experiencing widespread bleaching, scientist says