The world has a problem: Too many young people

By Somini Sengupta

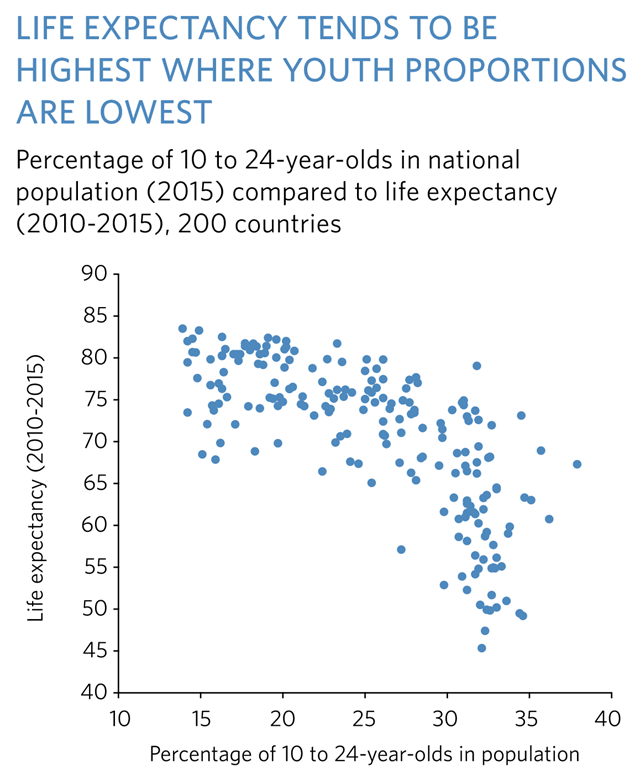

5 March 2016 (The New York Times) – At no point in recorded history has our world been so demographically lopsided, with old people concentrated in rich countries and the young in not-so-rich countries. Much has been made of the challenges of aging societies. But it’s the youth bulge that stands to put greater pressure on the global economy, sow political unrest, spur mass migration and have profound consequences for everything from marriage to Internet access to the growth of cities. The parable of our time might well be: Mind your young, or they will trouble you in your old age. A fourth of humanity is now young (ages 10 to 24). The vast majority live in the developing world, according to the United Nations Population Fund. Nowhere can the pressures of the youth bulge be felt as profoundly as in India. Every month, some one million young Indians turn 18 — coming of age, looking for work, registering to vote and making India home to the largest number of young, working-age people anywhere in the world.

Already, the number of Indians between the ages of 15 and 34 — 422 million — is roughly the same as the combined populations of the United States, Canada and Britain. By and large, today’s global youth are more likely to be in school than their parents were; they are more connected to the world than any generation before them; and they are in turn more ambitious, which also makes them more prone to getting fed up with what their elders have to offer. Many are in no position to land a decent job at home. And millions are moving, from country to city, and to cities in faraway countries, where they are increasingly unwelcome. Democratically elected presidents and potentates are equally aware: Aspirations, when thwarted, can be a potent, spiteful force. No longer can you be sure that a large swell of young working-age people will enrich your country, as they did a generation ago in East Asia. “You can’t just say, ‘Hey look, I’ve got a youth bulge, it’s going to be great,’ ” said Charles J. Kenny, an economist at the Washington-based Center for Global Development. “You’ve got to have an economy ready to respond.” “It is the big development challenge these countries face — more decent jobs,” he added. A case in point are the caste protests that paralyzed a prospering North Indian state in recent weeks. They were driven by a powerful landowning caste whose sons can neither support themselves through farming nor secure the jobs of their choice. So the protesters took to the streets demanding caste-based quotas for government posts. They blocked rail lines and set trucks on fire; the police say 30 people died in the unrest. This is just part of India’s staggering challenge. Every year, the country must create an estimated 12 million to 17 million jobs.

Worldwide, young workers are in precarious straits. Two out of five are either not working or working in such ill-paid jobs that they can’t escape poverty, according to figures recently released by the International Labour Organization. In the developing world, where few can afford to be unemployed, most young workers have jobs that are sporadic, poorly paid and offer no legal protection; women are worse off. Youth unemployment is especially striking in richer countries. Across Europe, youth unemployment is 25 percent, not just because of a sluggish economy but because many young Europeans don’t have the skills for the jobs available, from electricians to home health aides; it explains in part the surge of anti-immigrant sentiment on the Continent. In the United States, nearly 17 percent of those between the ages of 16 and 29 are neither in school nor working. That does not bode well. An increase in youth unemployment is a better predictor of social unrest than virtually any other factor, warned Raymond Torres, the Labour Organization’s research chief. “The social contract is weakened because of unfulfilled promises,” he said. [more]