Why we’ve been hugely underestimating the overfishing of the oceans

By Chelsea Harvey

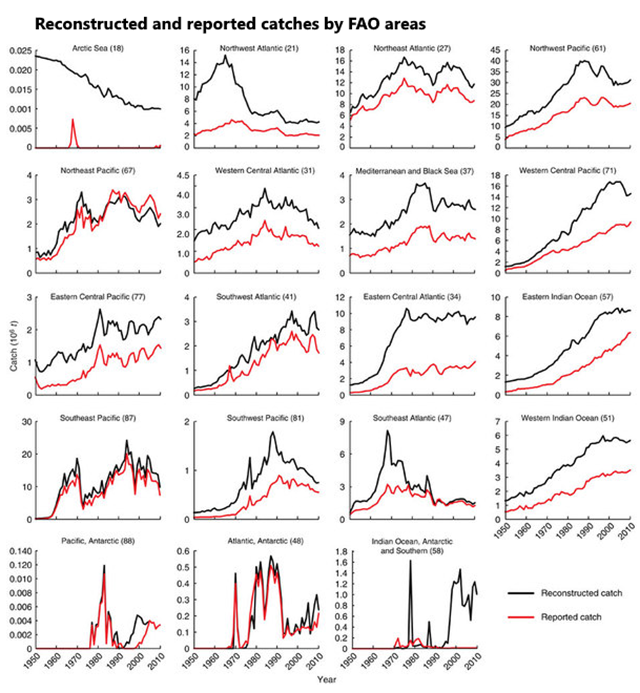

19 January 2016 (Washington Post) – The state of the world’s fish stocks may be in worse shape than official reports indicate, according to new data — a possibility with worrying consequences for both international food security and marine ecosystems. A study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications suggests that the national data many countries have submitted to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has not always accurately reflected the amount of fish actually caught over the past six decades. And the paper indicates that global fishing practices may have been even less sustainable over the past few decades than scientists previously thought. The FAO’s official data report that global marine fisheries catches peaked in 1996 at 86 million metric tons and have since slightly declined. But a collaborative effort from more than 50 institutions around the world has produced data that tell a different story altogether. The new data suggest that global catches actually peaked at 130 metric tons in 1996 and have declined sharply — on average, by about 1.2 million metric tons every year — ever since. The effort was led by researchers Daniel Pauly and Dirk Zeller of the University of British Columbia’s Sea Around Us project. The two were interested investigating the extent to which data submitted to the FAO was misrepresented or underreported. Scientists had previously noticed, for instance, that when nations recorded “no data” for a given region or fishing sector, that value would be translated into a zero in FAO records — not always an accurate reflection of the actual catches that were made. Additionally, recreational fishing, discarded bycatch (that is, fish that are caught and then thrown away for various reasons) and illegal fishing have often gone unreported by various nations, said Pauly during a Monday teleconference. “The result of this is that the catch is underestimated,” he said. So the researchers teamed up with partners all over the world to help them examine the official FAO data, identify areas where data might be missing or misrepresented and consult both existing literature and local experts and agencies to compile more accurate data. This is a method known as “catch reconstruction,” and the researchers used it to examine all catches between 1950 and 2010. Ultimately, they estimated that global catches during this time period were 50 percent higher than the FAO reported, peaking in the mid-1990s at 130 million metric tons, rather than the officially reported 86 million. As of 2010, the reconstructed data suggest that global catches amount to nearly 109 million metric tons, while the official data only report 77 million metric tons. […] The higher catch numbers suggest that fishing has been even more unsustainable in the past than scientists thought. And the world is now suffering the consequences, as the authors point out. Their second major finding was that fish catches have been sharply declining from the 1990s up through 2010 — much more severely than the FAO has reported. At first, the authors thought that these declines might be due to increased restrictions by certain countries on fishing quotas in recent years. But when the researchers removed those countries from their calculations, they found that the catch data was still caught up in a downward trend. “Our results indicate that the declining is very strong and the declining is not due to countries fishing less,” Pauly said during the teleconference. “It is due to the countries fishing too much and having exhausted one fish after the other.” The data indicate that the largest of these declines come from the industrial fishing sector. [more]

Why we’ve been hugely underestimating the overfishing of the oceans

ABSTRACT: Fisheries data assembled by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggest that global marine fisheries catches increased to 86 million tonnes in 1996, then slightly declined. Here, using a decade-long multinational ‘catch reconstruction’ project covering the Exclusive Economic Zones of the world’s maritime countries and the High Seas from 1950 to 2010, and accounting for all fisheries, we identify catch trajectories differing considerably from the national data submitted to the FAO. We suggest that catch actually peaked at 130 million tonnes, and has been declining much more strongly since. This decline in reconstructed catches reflects declines in industrial catches and to a smaller extent declining discards, despite industrial fishing having expanded from industrialized countries to the waters of developing countries. The differing trajectories documented here suggest a need for improved monitoring of all fisheries, including often neglected small-scale fisheries, and illegal and other problematic fisheries, as well as discarded bycatch.