A third of cacti facing extinction due to human encroachment, study finds – ‘The scale of the illegal wildlife trade, including trade in plants, is much greater than we previously thought’

5 October 2015 (AFP) – Thirty-one percent of cacti, some 500 species, face extinction due to human encroachment, according to the first global assessment of the prickly plants, published Monday. The finding places the cactus among the most threatened taxonomic groups on Earth, ahead of mammals and birds and just behind corals, according to the inter-government group International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). “The results of this assessment come as a shock to us,” lead researcher Barbara Goettsch, co-chair of the IUCN’s Cactus and Succulent Plant Specialist Group, said in a statement. “We did not expect cacti to be so highly threatened.” The IUCN Red List is widely recognized as the gold standard for measuring extinction risk for animals and plants. Cacti — native to the Americas, but introduced over centuries to Africa, Australia and Europe — are crucial links in the food chains of many animals, including humans. They are an essential sources of sustenance and water for deer, woodrats, rabbits, coyotes, lizards, and tortoises which, in return, help spread cacti seeds. […] Depending on the species and the region, different forces have driven the decline in cacti, found the study, published in Nature Plants. The top threat to cacti is expanding agriculture, especially in northern Mexico and the southern part of South America. Species native to coastal areas are being decimated by residential and commercial development, while in southern Brazil conversion of land for eucalyptus plantations is harming at least 27 species, some of them already on the endangered list. “Their loss could have far-reaching consequences for the biodiversity and ecology of arid lands and for local communities dependent on wild-harvested fruits and stems,” Goettsch said. Researchers were also surprised to find that illegal trade in highly-prized plants is also a key factor in their disappearance. “The scale of the illegal wildlife trade — including trade in plants — is much greater than we previously thought,” said Inger Andersen, IUCN director general. [more]

A third of cacti facing extinction due to human encroachment, study finds

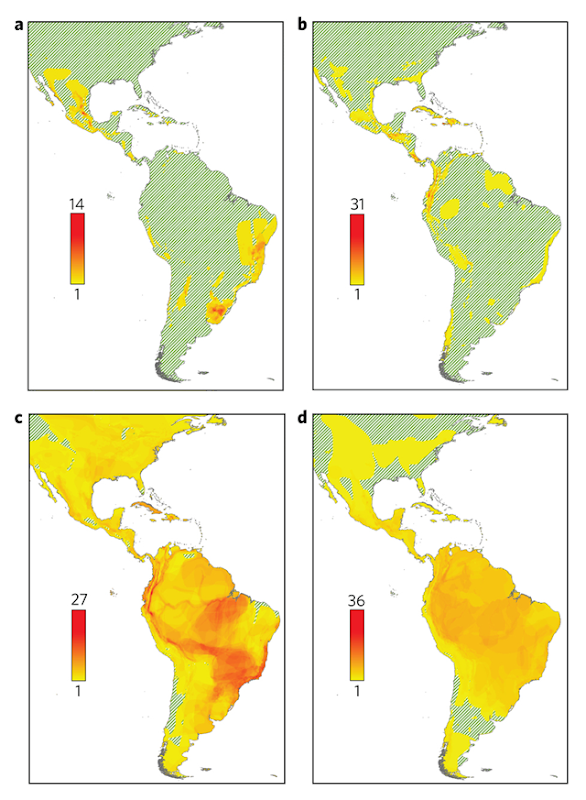

ABSTRACT: A high proportion of plant species is predicted to be threatened with extinction in the near future. However, the threat status of only a small number has been evaluated compared with key animal groups, rendering the magnitude and nature of the risks plants face unclear. Here we report the results of a global species assessment for the largest plant taxon evaluated to date under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Categories and Criteria, the iconic Cactaceae (cacti). We show that cacti are among the most threatened taxonomic groups assessed to date, with 31% of the 1,478 evaluated species threatened, demonstrating the high anthropogenic pressures on biodiversity in arid lands. The distribution of threatened species and the predominant threatening processes and drivers are different to those described for other taxa. The most significant threat processes comprise land conversion to agriculture and aquaculture, collection as biological resources, and residential and commercial development. The dominant drivers of extinction risk are the unscrupulous collection of live plants and seeds for horticultural trade and private ornamental collections, smallholder livestock ranching and smallholder annual agriculture. Our findings demonstrate that global species assessments are readily achievable for major groups of plants with relatively moderate resources, and highlight different conservation priorities and actions to those derived from species assessments of key animal groups. Plants are of fundamental importance to much of the rest of biodiversity and to many ecosystem functions, processes and services. However, the global status of plant species, that is their likelihood of extinction in the near future, remains poorly understood. Only 19,374 (6%) of an estimated ∼300,000 species1 have been evaluated against the current IUCN Red List Criteria2. Moreover, global species assessments, in which the extinction risk of every extant species in a taxonomic group is systematically assessed, have been conducted only for very few plant groups (such as cycads, conifers, mangroves, sea grasses3,4,5) of which most are not especially diverse. This situation is troublesome because there is evidence suggesting that the conservation status of plant species is of particular concern. Despite the small proportion of plants whose threat status has been evaluated, they nonetheless constitute a high proportion (47%) of all threatened species (across all kingdoms) currently on the IUCN Red List5. In addition, plant species are known to have geographic range sizes, a key correlate of extinction risk, that are on average smaller than those of many other groups; the smallest ranges are typically also much smaller than their equivalents among vertebrate groups6. Estimates of likely levels of recent and future plant extinction also indicate that these may be high7,8. Responding to this concern, determining the threat status of all known plant species, as far as is possible, has been identified as a key target for the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation 2011–2020 (ref. 9). This follows the global failure to meet the previous incarnation of this target as of 2010 (ref. 10). It is difficult to determine why, in contrast to vertebrates5,11,12, progress has been so slow, and comprehensive assessments of plant groups are so scarce. Likely reasons include the assumption that there is insufficient information available to assess most plant species against the IUCN Red List Criteria, including data on species’ geographic distributions (although much valuable distributional data undoubtedly reside, unsynthesized, in herbaria and botanical collections). In addition, plants lack the popular appeal of some animal groups, making it difficult to attract the funding to support global species assessments. And the costs of such assessments are thought to be restrictively high13,14,15,16,17,18. Here we challenge these assumptions, presenting the results of the largest comprehensive assessment to date of an entire plant taxon, the cacti, against the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (1,480 extant species of which 1,478 were evaluated, with two species for which no information could be obtained). We focus on the levels of threat to species, how species at different levels of threat are distributed, the nature of the threats and the practicality of such global species assessments for plants. The cacti are a culturally significant group, perceived as amongst the more charismatic of plant taxa. This has led to a long history of human use, including for private and public ornamental plant collections, leading to major conservation concerns. Surprisingly, only 11% of cactus species had been evaluated for the Red List before 2013. Cacti are distributed predominantly in, and are somewhat emblematic of, New World arid lands (only one species naturally occurs in Africa and Asia; Supplementary Table 1). Despite huge anthropogenic pressures, these regions have not attracted the conservation attention associated with other biomes, particularly tropical forests19,20.

In other news: http://www.forestethics.org/blog/oil-by-rail

It's quite tragic that the species loss is always far higher then being reported or recognized.

By my account, measurements (and then the published reports) appear to be off by at least 35%.

To determine this, go back and look at previous published estimates. Measure the escalation between the two to obtain the 35% error.

What this also means is current estimates are only accurate for events 2 – 3 year years ago or even longer. Actual species loss events now are at least 35% higher then being reported.

Within just a few years we're going to start seeing a terrifying rate of species extinctions as additional holes in the biosphere appear. It's probably likely that this won't be accurately reported until several years have passed.

Most published science is years behind the actual events being measured within the environment. If things were static, this wouldn't matter, but environmental changes are rapidly accelerating.

Policy makers and enforcement managers are unable to keep up with the accelerating losses. They're not even able to communicate how severe and fast and how widespread they're really are.

Humans are really out of touch with what is happening.