Dirty air sends millions to early grave: study – Without regulation, yearly deaths will increase to 6.6 million by 2050

By Noah Seelam

17 September 2015 (AFP) – Outdoor air pollution from sources as varied as cooking fires in India, traffic in the United States and fertiliser use in Russia, claim some 3.3 million lives globally every year, researchers said Wednesday. The vast majority of victims — nearly 75 percent — died from strokes and heart attacks triggered mainly by long-term inhalation of dust-like particles floating in the air. The remainder succumbed due to respiratory diseases and lung cancer, according to a study in the journal Nature. Smouldering cooking and heating fires in India and China were the single biggest danger — accounting for a third of deaths attributed to outdoor pollution, said study co-author Jos Lelieveld of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany. The new numbers support a 2014 World Health Organization report that blamed a similar number of deaths on outdoor pollution, and another 4.3 million per year on pollution within the home or other buildings. Unless stricter regulations are adopted, the number of deaths from outdoor pollution would double to 6.6 million by 2050, the team of international researchers forecast. “If this growing premature mortality by air pollution is to be avoided, intensive control measures will be needed especially in south and east Asia,” Lelieveld told journalists via conference call. He highlighted the “interesting” role of farm fertiliser. In Russia, the eastern United States and east Asia, agriculture was responsible for the bulk of pollution with fine particles under 2.5 microns in size — small enough to easily penetrate the lungs. A micron is a millionth of a metre. Ammonia released by fertiliser combines with the dangerous sulfates and nitrates in car exhaust fumes, to make the tiny particles. The combination is deadly in the Western world, said the team. Their calculations suggested car exhaust caused about 20 percent of pollution-related deaths in Britain, Germany, and the US — while the global average is about five percent. [more]

Dirty air sends millions to early grave: study

ABSTRACT: Assessment of the global burden of disease is based on epidemiological cohort studies that connect premature mortality to a wide range of causes1, 2, 3, 4, 5, including the long-term health impacts of ozone and fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 micrometres (PM2.5)3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. It has proved difficult to quantify premature mortality related to air pollution, notably in regions where air quality is not monitored, and also because the toxicity of particles from various sources may vary10. Here we use a global atmospheric chemistry model to investigate the link between premature mortality and seven emission source categories in urban and rural environments. In accord with the global burden of disease for 2010 (ref. 5), we calculate that outdoor air pollution, mostly by PM2.5, leads to 3.3 (95 per cent confidence interval 1.61–4.81) million premature deaths per year worldwide, predominantly in Asia. We primarily assume that all particles are equally toxic5, but also include a sensitivity study that accounts for differential toxicity. We find that emissions from residential energy use such as heating and cooking, prevalent in India and China, have the largest impact on premature mortality globally, being even more dominant if carbonaceous particles are assumed to be most toxic. Whereas in much of the USA and in a few other countries emissions from traffic and power generation are important, in eastern USA, Europe, Russia and East Asia agricultural emissions make the largest relative contribution to PM2.5, with the estimate of overall health impact depending on assumptions regarding particle toxicity. Model projections based on a business-as-usual emission scenario indicate that the contribution of outdoor air pollution to premature mortality could double by 2050.

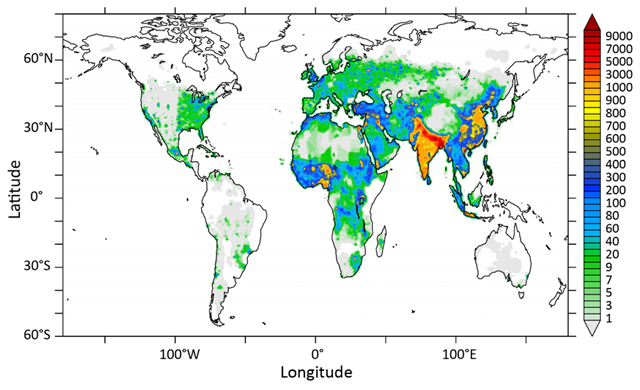

The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale