Unrestrained rubber expansion wreaking havoc on forests – ‘I’ve personally seen vast swaths of native forest being converted into rubber plantations in southern China, Malaysia, and Cambodia’

By Shreya Dasgupta

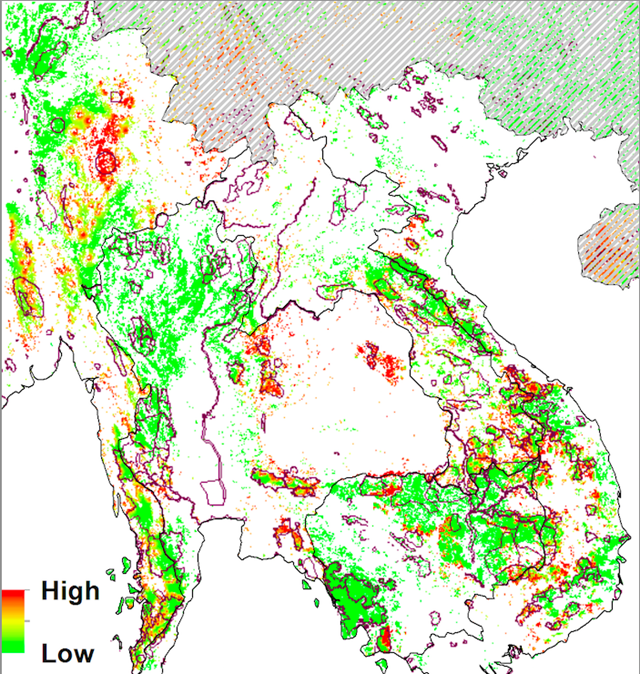

20 July 2015 (mongabay.com) – Your car tires may be treading over forests and wildlife in Southeast Asia. As the global demand for tires soars, so does the demand for natural rubber sourced from Hevea brasiliensis, the para-rubber tree. This rising demand is driving a rapid expansion of rubber plantations into biodiversity-rich forests and croplands of Southeast Asia, according to a new study published in Global Environmental Change. Between 2005 and 2010, for instance, rubber plantations replaced over 110,000 hectares of forests identified as key biodiversity areas and protected areas, the authors write. “I think it’s very alarming,” William Laurance, a professor and conservationist at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, who was not involved in the study, told mongabay.com. “Rubber is spreading rampantly in Southeast Asia-sort of a ‘second tsunami,’ following the explosive expansion of oil palm plantations in the region. I’ve personally seen vast swaths of native forest being converted into rubber plantations in southern China, Malaysia, and Cambodia.” Researchers from China, Singapore, UK and the U.S. evaluated where rubber occurs naturally, and examined the extent to which rubber plantations have spread in Southeast Asia – where nearly 97 percent of the world’s rubber is grown. This includes non-traditional areas where rubber was not historically grown, and where environmental conditions are not suitable for cultivation of rubber. “To our knowledge, this is the first study that provides a quantitative region-wide overview of the extent and trends of rubber plantation expansion into biophysically marginal environments,” said Antje Ahrends, a researcher at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and the World Agroforestry Centre, and lead author of the study. Rubber production in Southeast Asia increased from 300,000 metric tons in 1961 to over 5 million metric tons in 2011, a jump of more than 1,500 percent, the authors write. Most of this rubber production today is through monocultures. Traditionally, this was not the case. Rubber would usually be grown with timber trees, fruit trees, and other crops, Ahrends explained. “These rubber agroforests structurally resemble secondary forests.” On the other hand, rubber monocultures are structurally uniform and there is generally heavy application of fertilizers and pesticides, she added. “Research has shown that mixed rubber agroforests are of higher value for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem functioning than rubber mono-cultures, and of course they broaden income sources for farmers,” Ahrends said. “However, they are unfortunately also less productive.” Predictably, rubber agroforests are being increasingly replaced by rubber monocultures to increase productivity and, in turn, profit. And as monocultures expand, they eat into areas that are not conducive for rubber cultivation. [more]

Unrestrained rubber expansion wreaking havoc on forests

ABSTRACT: The first decade of the new millennium saw a boom in rubber prices. This led to rapid and widespread land conversion to monoculture rubber plantations in continental SE Asia, where natural rubber production has increased >50% since 2000. Here, we analyze the subsequent spread of rubber between 2005 and 2010 in combination with environmental data and reports on rubber plantation performance. We show that rubber has been planted into increasingly sub-optimal environments. Currently, 72% of plantation area is in environmentally marginal zones where reduced yields are likely. An estimated 57% of the area is susceptible to insufficient water availability, erosion, frost, or wind damage, all of which may make long-term rubber production unsustainable. In 2013 typhoons destroyed plantations worth US$ >250 million in Vietnam alone, and future climate change is likely to lead to a net exacerbation of environmental marginality for both current and predicted future rubber plantation area. New rubber plantations are also frequently placed on lands that are important for biodiversity conservation and ecological functions. For example, between 2005 and 2010 >2500 km2 of natural tree cover and 610 km2 of protected areas were converted to plantations. Overall, expansion into marginal areas creates potential for loss-loss scenarios: clearing of high-biodiversity value land for economically unsustainable plantations that are poorly adapted to local conditions and alter landscape functions (e.g., hydrology, erosion) – ultimately compromising livelihoods, particularly when rubber prices fall.

Current trends of rubber plantation expansion may threaten biodiversity and livelihoods