What happens when the sea swallows a country?

By Rachel Nuwer

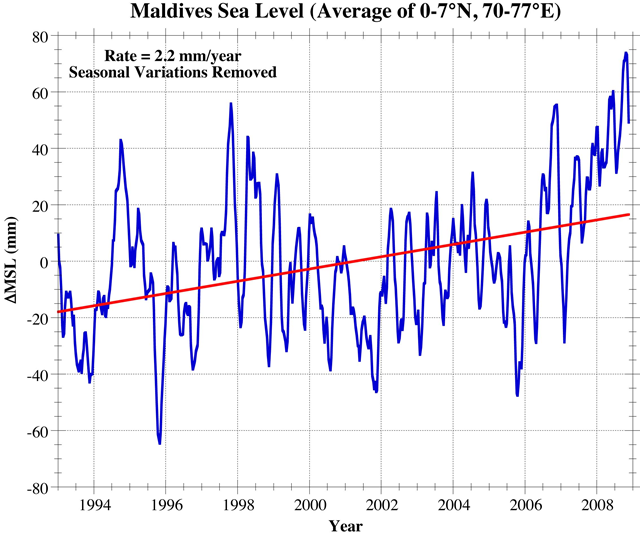

17 June 2015 (BBC) – As the seaplane lifts off the water’s surface and begins to climb, paradise opens up beneath us. The deep blue ocean stretches in every direction, but it is punctuated here and there by aquamarine discs of shallow coral reef that give way to the slightest slivers of white sand. Lavish hotels clinging to those oases sprout tentacles of bungalows, extending their small stake of precious solid ground. People come from all over the world to experience the impeccable luxury of the Maldives, a nation composed of around 1,200 islands, located 370 miles (595km) off the southernmost tip of India. Despite its remoteness, the resorts here – each located on its own private island – are unparalleled. Guests can sip $40 (£25.60) glasses of Champagne at freshwater pools’ swim-up bars, dine on Russian caviar and Wagyu steak, and stream the latest episode of Game of Thrones in their air-conditioned suite. Nothing is lacking, nothing is out of reach. Yet amid all this, a sinking realisation constantly undermines the islands’ carefully manicured perfection. It’s the knowledge that all of this may soon be gone. The nation, with its low-lying islands, has been labelled the most at-risk country in South Asia from the impact of climate change. Even if the swooning honeymooners do not allow this thought to mar their vacation, for the ever-smiling staff members, it’s harder to ignore. “Of course I’m concerned about climate change, about the reef, the environment and pollution,” says Mansoor, a Maldivian who works at one of the resorts. “But what can I do? I don’t know.” Climate change threatens waterfront developments and seaside cities around the world, but for some, the stakes are higher than simply having to move a few miles inland, or even having to relinquish large cities like Miami, Amsterdam and Shanghai. For the citizens of around six to 10 island nations, climate change could rob them of their entire country. While it’s impossible to know precisely what will happen in the future – and it’s worth pointing out that some research suggests a few island states might not be doomed by rising sea levels – many scientists fear that, no matter what mitigations we make, we’ve already condemned some countries to a physical disappearance. Even if we switched off all emissions now, we probably already have enough climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions to result in another foot or two of sea level rise in the coming years. “It might be that no amount of technology will allow us to prevent inundation of some low-lying island nations,” says Michael Mann, a renowned meteorologist at Pennsylvania State University. “That’s a reminder of what I like to call the procrastination penalty, of certain tipping points that we’ve physically and societally crossed.” If we somehow managed to cap our man-made temperature rise at just 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – as island nations have called for – most of them could remain above water. But most other nations, especially more developed ones, seem more comfortable considering a global temperature rise 2C or even 3C above pre-industrial levels. “The Pacific island states have been leading the pack in terms of alerting the planet Earth to the fact that these small islands, which produce almost zero greenhouse gas emissions, are sitting on the frontlines of climate change,” says Jose Riera, a special advisor at the UN. […] There is no legal, cultural or economic precedent for what happens to a group of nationals who no longer have a physical home. “A new concept of citizenship will have to be developed internationally,” says Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School. “I have confidence that island nations will still be states throughout this century, but the next one is another question, with many uncertainties.” [more]

What happens when the sea swallows a country?