Video: Decline of Arctic sea ice, 1987-2014

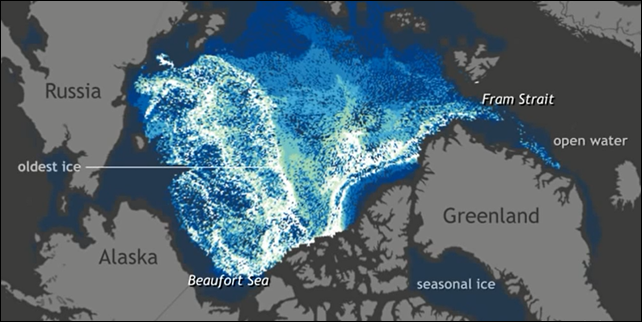

20 January 2015 (NOAA) – Each winter, sea ice expands to fill nearly the entire Arctic Ocean basin, reaching its maximum extent in March. Each summer, the ice pack shrinks, reaching its smallest extent in September. The ice that survives at least one summer melt season tends to be thicker and more likely to survive future summers. Since the 1980s, the amount of this perennial ice (sometimes called multiyear) has declined. This animation tracks the relative amount of ice of different ages from 1987 through early November 2014. The first age class on the scale (1, darkest blue) means “first-year ice,” which formed in the most recent winter. (In other words, it’s in its first year of growth.) The oldest ice (>9, white) is ice that is more than nine years old. Dark gray areas indicate open water or coastal regions where the spatial resolution of the data is coarser than the land map. As the animation shows, Arctic sea ice doesn’t hold still; it moves continually. East of Greenland, the Fram Strait is an exit ramp for ice out of the Arctic Ocean. Ice loss through the Fram Strait used to be offset by ice growth in the Beaufort Gyre, northeast of Alaska. There, perennial ice could persist for years, drifting around and around the basin’s large, looping current. Around the start of the 21st century, however, the Beaufort Gyre became less friendly to perennial ice. Warmer waters made it less likely that ice would survive its passage through the southernmost part of the gyre. Starting around 2008, the very oldest ice shrank to a narrow band along the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

Recent Conditions

In September 2012, Arctic sea ice melt broke all previous records. Melt was less severe in 2013 and 2014. According to the 2014 Arctic Report Card, the less extreme melting provided an opportunity for a bit more first-year ice to become perennial ice. Between March 2013 and March 2014…

- first-year ice decreased from 78 percent to 69 percent, suggesting that a substantial portion of Arctic sea ice survived the 2013 summer melt;

- second-year ice increased from 8 to 14 percent;

- fourth-year and older ice rose from 7.2 to 10.1 percent.

Overall, the amount of perennial sea ice in March 2014 rose enough to approximate the 1981-2010 median. (Median means “middle,” as in half of the years in the record had a larger extent of perennial ice, and half had a smaller extent.) While perennial ice increased between 2013 and 2014, the long-term trend continues to be downward, the Report Card authors stated. In 1980s, the oldest ice (fourth-year ice and older) comprised 26 percent of the ice pack; as of March 2014, it was 10%. And as the animation above shows, very old ice (say, 7-8 years or older) has become even more rare. Animation by NOAA Climate.gov team, based on research data provided by Mark Tschudi, CCAR, University of Colorado. Sea ice age is estimated by tracking of ice parcels using satellite imagery and drifting ocean buoys.

References

Charctic Interactive Sea Ice Graph. National Snow and Ice Data Center. Accessed November 25, 2014. Perovich, D., Gerland, S., Hendricks, S., Meier, W., Nicolaus, M., Tschudi, M. (2014) Sea Ice. In Jeffries, M.O., Richter-Menge, J., Overland, J.E. (Eds.), Arctic Report Card: Update for 2014.