Lake Urmia: How Iran’s most famous lake is disappearing

By Ali Mirchi, Kaveh Madani, and Amir AghaKouchak for Tehran Bureau

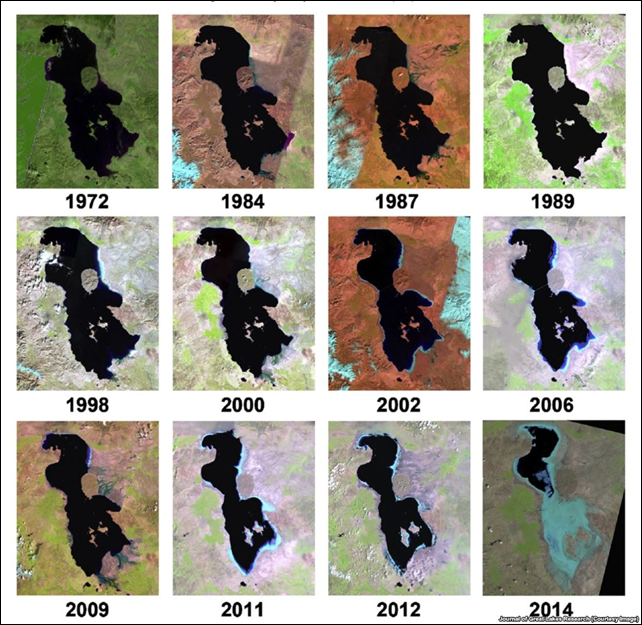

23 January 2015 (The Guardian) – In the late 1990s, Lake Urmia, in north-western Iran, was twice as large as Luxembourg and the largest salt-water lake in the Middle East. Since then it has shrunk substantially, and was sliced in half in 2008, with consequences uncertain to this day, by a 15-km causeway designed to shorten the travel time between the cities of Urmia and Tabriz. Historically, the lake attracted migratory birds including flamingos, pelicans, ducks, and egrets. Its drying up, or desiccation, is undermining the local food web, especially by destroying one of the world’s largest natural habitats of the brine shrimp Artemia, a hardy species that can tolerate salinity levels of 340 grams per litre, more than eight times saltier than ocean water. Effects on humans are perhaps even more complicated. The tourism sector has clearly lost out. While the lake once attracted visitors from near and far, some believing in its therapeutic properties, Urmia has turned into a vast salt-white barren land with beached boats serving as a striking image of what the future may hold. Desiccation will increase the frequency of salt storms that sweep across the exposed lakebed, diminishing the productivity of surrounding agricultural lands and encouraging farmers to move away. Poor air, land, and water quality all have serious health effects including respiratory and eye diseases. The people of the north west – mainly Azeris and Kurds – are raising their voices. The Azeris, one of Iran’s most influential ethnic groups and about a third of the country’s population, venerate Urmia as a symbol of Azeri identity, dubbing it “the turquoise solitaire of Azerbaijan”. The region is also home to many Kurds, who are demanding a bigger say in the management of the lake to improve the livelihood of Kurdish communities. President Hassan Rouhani has shown he is listening, referring to Urmia during his election campaign, and subsequently promising the equivalent of $5 billion to help revive the lake over ten years. Solutions, however, require agreement on the main causes of the problem, and this motivated a group of concerned Iranian researchers in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom to carry out an independent, first-hand assessment beginning in 2013. Because of the unavailability of reliable and consistent ground-truth data, the team used high-resolution satellite observations over the past four decades to estimate the lake’s physiographic changes. The results of this investigation, which recently appeared in the Journal of Great Lakes Research, revealed that in September 2014 the lake’s surface area was about 12% of its average size in the 1970s, a far bigger fall than previously realised. The research undermines any notion of a crisis caused primarily by climate changes. It shows that the pattern of droughts in the region has not changed significantly, and that Lake Urmia survived more severe droughts in the past. [more]

Lake Urmia: how Iran’s most famous lake is disappearing

ABSTRACT: Lake Urmia, one of the largest saltwater lakes on earth and a highly endangered ecosystem, is on the brink of a major environmental disaster similar to the catastrophic death of the Aral Sea. With a new composite of multi-spectral high resolution satellite observations, we show that the area of this Iranian lake has decreased by around 88% in the past decades, far more than previously reported (~25% to 50%). The lake’s shoreline has been receding severely with no sign of recovery, which has been partly blamed on prolonged droughts. We use the lake basin’s satellite-based gauge-adjusted climate record of the Standardized Precipitation Index data to demonstrate that the on-going shoreline retreat is not solely an artifact of prolonged droughts alone. Drastic changes to lake health are primarily consequences of aggressive regional water resources development plans, intensive agricultural activities, anthropogenic changes to the system, and upstream competition over water. This commentary is a call for action to both develop sustainable restoration ideas and to put new visions and strategies into practice before Lake Urmia falls victim to the Aral Sea syndrome.