Biggest Brazil metro area desperate for water – ‘If deforestation in the Amazon continues, São Paulo will probably dry up’

By Adriana Gomez Licon

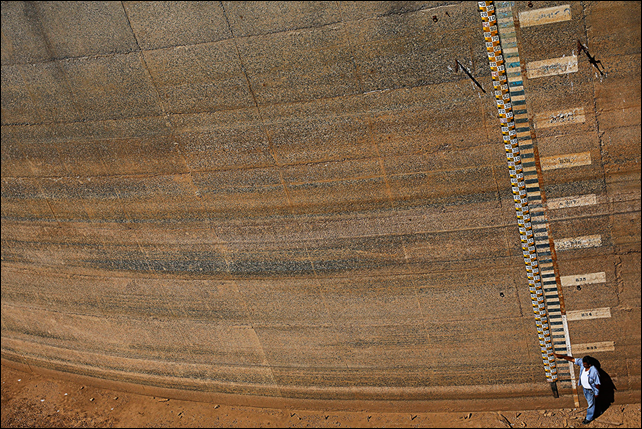

8 November 2014 ITU, Brazil (AP) – It’s been nearly a month since Diomar Pereira has had running water at his home in Itu, a commuter city outside São Paulo that is at the epicenter of the worst drought to hit southeastern Brazil in more than eight decades. Like others in this city whose indigenous name means “big waterfall,” Pereira must scramble to find water for drinking, bathing and cooking. On a recent day when temperatures hit 90 degrees (32 Celsius), he drove to a community kiosk where people with empty soda bottles and jugs lined up to use a water spigot. Pereira filled several 13-gallon containers, which he loaded into his Volkswagen bug. “I have a job and five children to raise and am always in a rush to find water so we can bathe,” said Pereira, a truck driver who makes the trip to get water every couple of days. “It’s very little water for a lot of people.” Brazil is approaching the December start of its summer rainy season with its water supply nearly bare. More than 10 million people across São Paulo state, Brazil’s most populous and the nation’s economic engine, have been forced to cut water use over the past six months. A reservoir used by Itu has fallen to 2 percent of capacity and, because its system relies on rain and groundwater rather than rivers, the city is suffering more than others. In Itu, desperation is taking hold. Police escort water trucks to keep them from being hijacked by armed men. Residents demanding restoration of tap water have staged violent protests. Restaurants and bars are using disposable cups to avoid washing dishes, and agribusinesses are transporting soybeans and other crops by road rather than by boat in areas where rivers have dried up. “We are entering unknown territory,” said Renato Tagnin, an expert in water resources at the environmental group Coletivo Curupira. “If this continues, we will run out of water. We have no more mechanisms and no water stored in the closet.” The Sao Paulo metropolitan area ended its last rainy season in February with just a third of the usual rain total only 9 inches (23 centimeters) over three months. Showers in October totaled just 1 inch (25 millimeters), one-fifth of normal. Only consistent, steady summer rains will bring immediate relief, experts say. […] Authorities forced the city of 160,000 to cut its daily water consumption from 16 million gallons (62 million liters) to 2 million gallons (8 million liters). Dozens of water trucks are deployed to bring in water from far off towns. Huge 5,000-gallon tanks have been set up around the city. [more]

Biggest Brazil metro area desperate for water

By Wyre Davies

7 November 2014 (Rio de Janeiro) – In Brazil’s biggest city, a record dry season and ever-increasing demand for water has led to a punishing drought. It has actually been raining quite heavily over the last few days in and around São Paulo but it has barely made a drop of difference. The main reservoir system that feeds this immense city is still dangerously low, and it would take months of intense, heavy rainfall for water levels to return to anything like normal. So how does a country that produces an estimated 12% of the world’s fresh water end up with a chronic shortage of this most essential resource – in its biggest and most economically important city? It’s interesting to note that both the local state government and the federal government have been slow to acknowledge there is a crisis, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. That might have been a politically expedient position to take during the recent election campaign, when the shortage of water in Sao Paulo was a thorny political issue, but the apparent lack of urgency in the city and wider state now is worrying many. At the main Cantareira reservoir system, which feeds much of this city’s insatiable demand for water, things have almost reached rock bottom. Huge pipes suck out what water remains as the reservoir dips below 10% of its usual capacity. The odd local villager wanders around the dry bed of the lake hoping for a temporary windfall as fish flounder in the few pools that remain. In the town of Itu, not far from the slowly diminishing reservoir, Gilberto Rodriguez and several of his neighbours wait patiently in line. All of them are carrying as many jerry cans, empty plastic drinks bottles or buckets as they can muster. For weeks now they’ve been filling up with water from this emergency well. Twice a day Gilberto heaves the full containers into his car and heads home. Every other house on the short drive seems to have a homemade poster pinned to the gate or doorframe. The same message, or plea, is written on each one: “Itu pede Socorro” – “Itu needs help”. Gilberto and his wife almost break into a laugh when I suggest to them that, according to São Paulo’s state government, the situation is manageable and there’s no need for water rationing. “There’s been no water in our pipes now for a month,” says Soraya. […] Antonio Nobre is one of country’s most respected Earth scientists and climatologists. He argues there is enough evidence to say that continued deforestation in the Amazon and the almost complete disappearance of the Atlantic forest has drastically altered the climate. “There is a hot dry air mass sitting down here [in São Paulo] like an elephant and nothing can move it,” says the eminent scientist, who divides his time between the southern city of São Jose dos Campos and the Amazon city of Manaus. “That’s what we have learned – that the forests have an innate ability to import moisture and to cool down and to favour rain… If deforestation in the Amazon continues, São Paulo will probably dry up. If we don’t act now, we’re lost,” adds Mr Nobre, whose recent report on the plight of the Amazon caused a huge stir in scientific and political circles. [more]

Brazil drought: Sao Paulo sleepwalking into water crisis

By Andrew Maddocks Andrew Maddocks, Tien Shiao, and Sarah Alix Mann

4 November 2014 (WRI) – The worst drought to grip São Paulo, Brazil, and neighboring states in 80 years is wreaking havoc on the local population. As of late October, key reservoirs hold less than two weeks’ worth of drinking water. Schools and health centers are closing early, dishes sit unwashed in sinks, and restaurants are steering customers away from restrooms. Significant crop production declines are of deep concern, and because 50 percent of Brazil’s electrical energy comes from hydropower, possible power cuts loom. The president of Brazil’s Water Regulatory Agency warned that if the drought continues, the state faces “a collapse like we’ve never seen before.” Brazil has more freshwater than any country in the world – 12 percent of the entire planet’s total volume. So how is São Paulo—the richest, largest city in South America—running out of water? Three maps help tell the complicated story. […]3) It’s a Deforestation Problem.

Expert consensus is building around deforestation as a major driver of this year’s drought and other serious dry periods in Brazil. In 2009, Antonio Nobre, a scientist at Brazil’s Center for Earth Systems Science – CCST/INPE, warned that Amazonian deforestation could interfere with the forest’s function as a giant water pump; it lifts vast amounts of moisture up into the air, which then circulate west and south, falling as rain to irrigate Brazil’s central and southern regions. Without these “flying rivers,” Nobre said, the area accounting for 70 percent of South America’s GNP could effectively become desert. In recent years, Brazil has been hailed for its efforts to reduce deforestation—the average rate of clearance decreased 70 percent between 2005 and 2014. However, deforestation in Brazil jumped during the last officially recorded period, between August 2012 and July 2013, marking the first increase since 2008. Satellite analysis from Imazon, a Brazilian NGO, also indicates a 190 percent surge in forest clearing this August and September when compared with last year. See the animation above, showing tree-cover loss equivalent to an area almost five times the size of New York City. In January and February of this year, when rain is usually abundant in central and southern Brazil, the flying rivers failed to flow south, according to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The animation of tree cover loss alerts from Global Forest Watch is meant to be illustrative only. The exact science of how forest clearing affects the performance of the Amazon’s “hydrological pump” is still emerging, and further analysis is needed to determine how the timing and location of forest loss affects precipitation elsewhere. The “Flying Rivers Project,” an effort by Dr. Nobre and other Brazilian scientists to quantify the dynamics of atmospheric water vapor and forests in Brazil, provides some of the most robust data on the subject, including real-time and historic maps of air flows and water vapor in the region. [more]