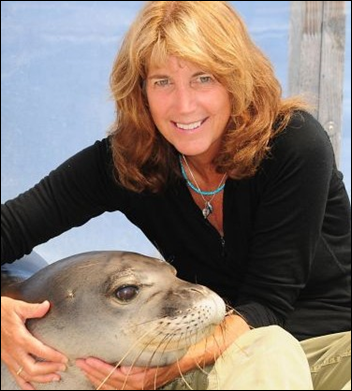

By Terrie M. Williams

By Terrie M. Williams

6 November 2014 (Los Angeles Times) — As I rubbed the frostbite out of my hands on returning from a seal survey on Antarctic ice recently, I was informed that I had the dubious distinction of making the Top 5 in the 2014 list of wasteful scientists compiled by Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.). According to Coburn’s “Wastebook,” I had egregiously squandered $856,000 of taxpayer money on training mountain lions to walk on a treadmill. The project the senator referred to was to design and test a new high-tech wildlife collar that measured the instantaneous energy use, hunting behavior and movement patterns of large carnivores such as mountain lions. Our goal was to provide a new tool for wildlife conservation. The project took four years and involved many biologists, engineers, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, undergraduate students and research technicians. Ultimately, we developed an innovative technology for monitoring wild carnivores. And, yes, the research involved calibrating the specially designed collars on three mountain lions trained to walk on a treadmill; this was followed by tests on free-ranging wild lions in the Santa Cruz Mountains. The wildlife collars we designed can be used to avoid human-animal conflicts by predicting when and where predatory animals hunt. In the process, they will help save human lives, our pets and livestock, as well as the large predatory mammals that represent the “top-of-the-food chain” glue holding our ecosystems together. It is a problem that’s all too familiar in densely populated California, where human-wildlife encounters have increased. The senator’s misrepresentation of our research has the potential to affect wildlife conservation for years to come. The reaction to the mountain-lions-on-treadmill sound bite has been swift, with people in the media and across the Internet calling our project “dubious,” “absurd,” “ridiculous,” “outlandish” and more. They judged without reading the study; they condemned without contacting us. We even made the monologues of late-night comedians. The public was misinformed about science and scientists. How this will reverberate among funding agencies and the next generation of wildlife biologists is unknown. Currently, the funding level for animal biology at the National Science Foundation — the primary agency supporting biological research on marine and terrestrial wildlife — is at an all-time low. Less than 10% of grant proposals submitted to the biological division of the agency get funded. The level is even more dismal for proposals focusing on large animals such as lions, wolves, pandas, dolphins or elephants. The fact is, grant proposals on single-celled organisms are 26 to 44 times more likely to be funded than those studying big wild animals. This lack of funding has created a deficit in knowledge that has left humans in the dark about the basic biology of large wild animals and how to live with them. More than 25% of the world’s mammals are threatened with extinction. More than half of all mammalian species populations are now in decline, with the largest mammals disappearing at exceptionally high rates. River dolphins, African lions, monk seals, cheetahs, mountain gorillas and vaquitas — the rarest porpoise that lives in the northern Gulf of California — are slipping away before our eyes. The cost to our ecosystem from the loss of so many species is unknown. How many cards can you remove before the entire house falls down? [more]

As species decline, so does research funding

By Terrie M. Williams

I realize this blog is not suppose to be funny, but just thinking about it makes me laugh. I guess I am a bit of a nihilist, but the way you guys have repackaged Judeo-Christianity and replaced "god" with the earth is hilarious.