Derelict fishing nets have turned the bottom of the sea into a death trap

By Gwynn Guilford

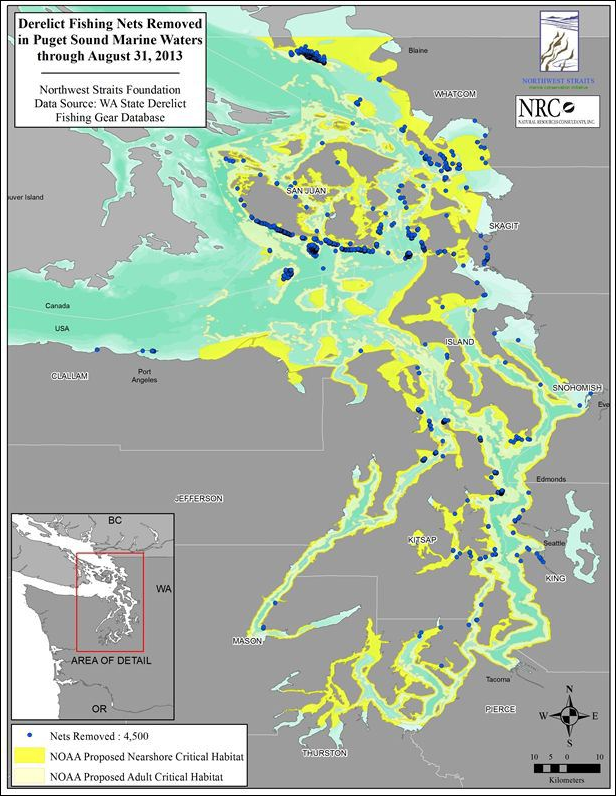

13 August 2014 (Quartz) – Each year, at least 640,000 tonnes of nets and other fishing gear goes overboard and never comes back. But just because it’s lost to the sea doesn’t mean that derelict gear stops doing its jobs. The lobster pots, crab traps and dense thickets of nets that litter the sea bottom keep snaring fish and other animals for years or even decades after they go missing. It’s impossible to estimate how many marine animals are killed each year by “ghost fishing,” as the problem is known. However, the mosaic of local reports suggests staggering numbers—many of them of commercially valuable or endangered species. In Puget Sound, ghost gear is thought to kill more 3.5 million animals a year, including nearly 25 seals, porpoises and other marine mammals a week. This is obviously bad for fishermen. In the case of Puget Sound, around $335,000 worth of Dungeness crabs (pdf, p.13) are killed annually. However, because ghost fishing is largely an unseen phenomenon, only a dozen or so local governments around the world have implemented measures to stop this. To date, much of the more daring cleanup efforts have been spearheaded by teams of volunteer divers in 15 countries around the world that have formed a group called Ghost Fishing, which often works in partnership with governments.

Launched in 2009, Ghost Fishing grew out of a group of recreational shipwreck divers in the Netherlands that began collecting derelict fishing gear during dives in the North Sea. Shipwrecks, it turns out, are often ghost fishing hubs, says Chuck Kopczak, a diver with Ghost Fishing’s crew in California. “The perversity of the whole thing is that fish and other marine life tend to be attracted to structure on the bottom—whether it’s a rocky reef or coral reef or a shipwreck. So fishermen will set their nets above the wrecks,” says Kopczak. When a net becomes untethered, it’s easy for it to snag on one of the wreck’s many jagged edges. “These manmade structures are almost like magnets for these things.” Because more recent generation of nets are designed to be hard for fish to see, fish and other animals are easily entangled. Sharks and other predators that approach the entangled fish as bait often become ensnared themselves. Depending on the species, and the type of net, ghost nets catch anywhere from 5% to 30% of the number of target species caught by fishermen’s nets. All told, a single net can kill hundreds of pounds of commercial species per day, along with a slew of other animals. [more]

Derelict fishing nets have turned the bottom of the sea into a death trap