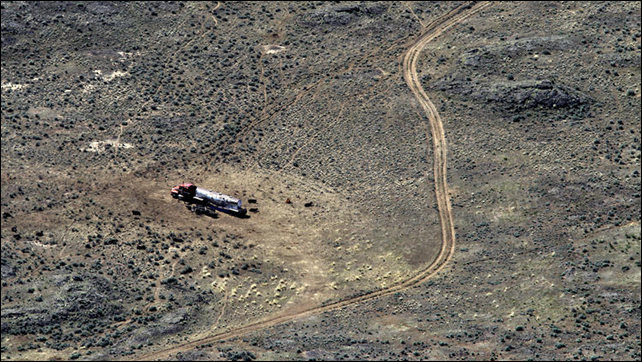

Drought threatens grazing on U.S. land – Federal land can’t continue to support livestock and wildlife – ‘To be honest with you, I think our way of life is pretty much going to be over in 10 years’

By Julie Cart

15 June 2014 Snake River Plain, Idaho (Los Angeles Times) – There’s not much anyone can tell Barry Sorensen about Idaho’s Big Desert that he doesn’t know. Sorensen, 72, and his brother have been running cattle in this sere landscape all their lives, and they’ve weathered every calamity man and nature have thrown at them — until this drought came along. Sitting recently in a rustic cabin where he spends many months looking after his cattle, Sorensen’s voice was tinged with defeat. “To be honest with you,” he said, “I think our way of life is pretty much going to be over in 10 years.” Years-long drought has pummeled millions of acres of federal rangeland in the West into dust, leaving a devastating swath from the Rockies to the Pacific. Add to that climate change, invasive plants and wildfire seasons that are longer and more severe, and conditions have reached a breaking point in many Western regions. The land can no longer support both livestock and wildlife. “All these issues — it’s changing the landscape of the West, dramatically,” said Ken Wixom, who grazes 4,000 ewes and lambs on BLM land in the Snake River Plain. For public lands ranchers like him who depend on federal acreage to sustain their animals, the mood ranges from brooding to surrender. The situation was spelled out in stark terms in two recent letters from the federal Bureau of Land Management. They told the ranchers what they already knew: Unless something changes, the days of business as usual on the 154 million acres of federal grazing land are over. This drought-stressed range in Idaho can no longer sustain livestock, the letter warned. Better plan to reduce herd numbers by at least 30% for the spring turnout. “I knew it was coming,” said Sorensen, squinting as the afternoon sun poured through a window. […] Livestock shares the range with wildlife, including the greater sage grouse, a species dependent on sagebrush and native grasslands to survive. The grouse population has plummeted by 93% in the last 50 years, and its habitat has shrunk to one-quarter of its former 240,000-square-mile range. If the federal government grants endangered species protection to the grouse sometime next year, ranching on federal land will be cut back even more, federal officials say. In some regions, public lands ranching might end altogether. The problem for livestock and wildlife alike is that the drought has been merciless on all plants in the West. Last week 60% of the 11 Western states were experiencing some degree of serious drought. Climate change has altered weather patterns so much that vegetation in some regions is transforming from abundant sagebrush, grass and forbs to a new landscape of weeds and cheat grass — fast-burning fuels that propel wildfire and destroy rangeland. In southern New Mexico, the transformation has gone one step further — from sagebrush to weeds to sand-blown desert — and biologists say the pattern is likely to be repeated across the West. If that happens, the economics of cattle ranching will unravel. Public lands grazing is a remnant of Washington’s interest in settling the West by providing a financial leg up to covered-wagon pioneers and private interests alike. Ranchers pay a fee, far below market rate, for each mother cow and calf they turn out to graze on BLM acreage. [more]