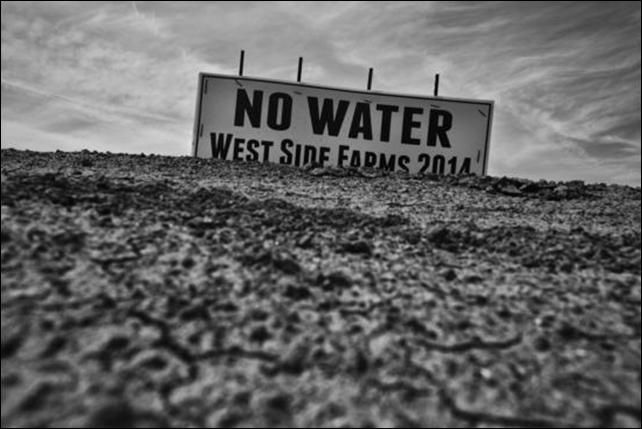

California drought yields only desperation – ‘It’s going to get worse. They’re not planting. Think what it will be like at harvest.’

By Diana Marcum

30 May 2014 HURON, California (Los Angeles Times) – The two fieldworkers scraped hoes over weeds that weren’t there. “Let us pretend we see many weeds,” Francisco Galvez told his friend Rafael. That way, maybe they’d get a full week’s work. They always tried to get jobs together. Rafael, the older man, had a truck. Galvez spoke English. And they liked each other’s jokes. But this was the first time in a month, together or alone, that they’d found work. They were two men in a field where there should have been two crews of 20. A farmer had gambled on planting drought-resistant garbanzo beans where there was no longer enough water for tomatoes or onions. Judging by the garbanzo plants’ blond edges, it was a losing bet. Galvez, 35, said his dream is to work every day until he is too bent and worn, then live a little longer and play with his grandchildren. He wants to buy his children shoes when they need them. His oldest son needed a pair now. Most of all, he wants to stay put. But the slowly unfurling disaster of California’s drought is catching up to him. Each day more families are leaving for Salinas, Arizona, Washington — anywhere they heard there were jobs. Even in years when rain falls and the Sierra mountains hold a snowpack that will water almonds and onions, cattle and cantaloupes, Huron’s population swells and withers with the season. These days in Huron — and Mendota and Wasco and Firebagh and all the other farmworker communities on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley — even the permanent populations are packing up. “The house across the street from us — they all left yesterday,” Galvez said. “Maybe this town won’t be here anymore?” Since the days of the Dust Bowl, these have been the places where trouble hits first and money doesn’t last. […] The illusion of lushness was there. But without the rains, even California’s vast system of buying, selling, pumping and moving trillions of gallons of water from the Sacramento Delta to this dry, clay-bottom plain — even pumping so much groundwater that parts of the Central Valley sink a foot a year — wasn’t enough to keep Huron working. The main drag was as sleepy as the stray dogs napping in every shady doorway. Two men in cowboy hats gossiped on a bench. A daily afternoon poker game was languidly being played in a window booth at a near-empty cafe. “Only for fun, no money,” the waitress said, though there were clearly stacks of bills on the table. Huron already whispered of the ghost town it could soon be: It has a $2-million deficit. Only about 1,000 people in a town with a permanent population of 7,000 are registered to vote, and of those, only some 200 actually do. No one has declared for the two open City Council seats — including the incumbents. Each week at school, Galvez’s children have fewer classmates. Antonio Chavarrias, a fieldworker, said the drought is different from other natural disasters because it doesn’t end. This is the third year of drought but, he said, just the beginning of the hardships. “It’s going to get worse,” he said. “They’re not planting. Think what it will be like at harvest.” […] Mormons were at Galvez’s house — two blond, Spanish-speaking women from Utah who had been coming weekly. Down the street, a man in a crisp plaid shirt was walking around in the heat, shaking hands and introducing himself to everyone he passed. He was an evangelical pastor from Lemoore. The drought is bringing a lot of religion to Huron. Ministers walk the streets; bars notorious for violence and prostitution are empty. “We’ve been having less problems downtown,” said Police Chief George Turegano, a retired Capitola officer. “People have less money in their pocket. They’re saving it to move to the next town, the next job.” [more]