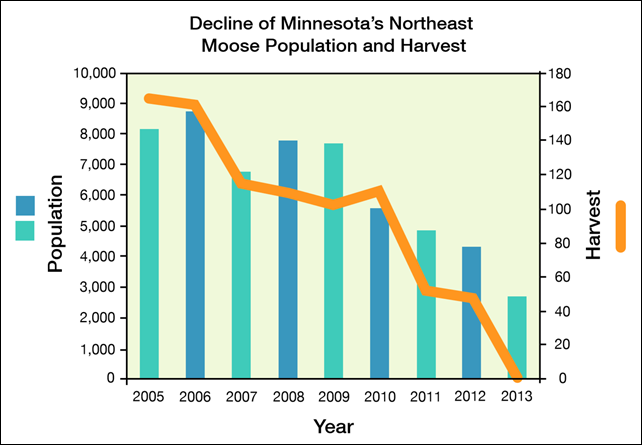

Graph of the Day: Decline of Minnesota’s northeast moose population and harvest, 2005-2013

13 November 2013 (NWF) – Minnesota’s northwest moose population, one of only two populations in the state, was essentially gone by 2008, numbering fewer than 100 animals, down from a population of about 4,000 just 25 years earlier. In the four decades during which the population plummeted, summer temperatures increased 3 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit, and this is considered an important factor in the herd’s decline. Harvest of Minnesota’s northwest herd was permanently closed in 1997, although hunting was not considered to be an important factor in the population’s decline. A more insidious climate impact on moose is the greater survival of winter ticks facilitated by warmer and shorter winters. In Minnesota, some moose have been found burdened by 50,000 to 70,000 winter ticks—ten to twenty times more than normal. (The winter tick species isn’t known to parasitize humans or infect them with disease, unlike the deer tick and blacklegged tick which can transmit Lyme disease to humans.) Heavy winter tick infestations leave moose weakened from blood loss, in poor health, and with greater vulnerability to disease. Winter ticks can cause significant increases in moose mortality. Another disturbing aspect of heavy winter tick infestations is the effort of moose to rid themselves of the winter ticks by rubbing against trees. This causes their hair to break off at the base, which is white. These resulting “ghost” moose are then without insulating hair, leaving them vulnerable to cold exposure and death. The future of moose, moose watching, and moose hunting in Minnesota appears grim. With Minnesota’s northwest herd virtually gone, Minnesota’s only remaining viable moose population inhabits the northeastern part of the state and is now itself in precipitous decline. From an estimated population of about 8,000 moose in 2004 through 2009, the population plummeted to only about 3,000 animals by 2013. Now under intense investigation, the stress of warming temperatures associated with climate change is very likely increasing the vulnerability of moose to disease and other natural factors. Moose hunting ceased altogether in Minnesota when the state’s Department of Natural Resources announced a closure of the 2013 hunting season for the northeast population. “The state’s moose population has been in decline for years but never at the precipitous rate documented this winter,” said Tom Landwehr, DNR commissioner. New Hampshire’s moose are also being harmed by surging winter tick populations, associated with warmer winters. In 2002 winter ticks were blamed for a large number of moose deaths. Heat also affects moose directly, as summer heat stress leads to dropping weights, a fall in pregnancy rates, and increased vulnerability to predators and disease. When it gets too warm, moose typically seek shelter rather than forage for the nutritious foods needed to keep them healthy. Due primarily to these factors, New Hampshire’s moose population has declined by 3,100 moose, which is more than 40 percent, since 1997. The New Hampshire Fish and Game Department has reduced the number of moose hunting permits by 60 percent in the last five years. Moose in some areas of the West are also challenged by climate change. Wyoming’s moose herd is currently at just over 50 percent of desired management objectives. A decade of drought fueled by rising temperatures and declining rainfall associated with climate change appear to be reducing the quality of moose habitat. Indeed, western states have experienced extensive climate-induced aspen die-off driven by higher summer temperatures causing drought. Aspen is a preferred forage species for moose and it has declined by about 50 percent in Wyoming. As populations drop in the warmer southern portions of the moose’s range and the climate continues to warm, the future of moose hunting in these areas appears bleak. All moose hunting in Minnesota has been closed, and the likelihood of future moose hunting in Minnesota is highly doubtful. Over the past decade, Wyoming’s moose harvest and moose hunter expenditures, a boost to outfitters and local economies, have declined about 60 percent. Since 2007, New Hampshire’s moose harvest has also declined by 60 percent.

Report: Climate Change Leaving America’s Big Game Nowhere to Run

Large mammals are among the most vulnerable to climate change, especially the non-migratory. Bears are in decline throughout the northern United Slaves, reaching up into Canada, the Northwest Territories and of course, Alaska.