Climate change is ‘killing Argentina’s Magellanic penguin chicks’

By Matt McGrath

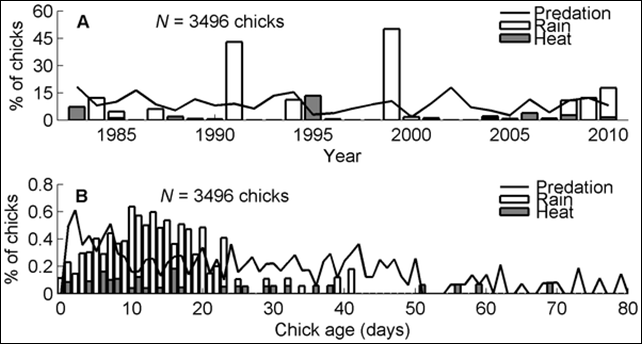

29 January 2014 (BBC News) – Penguin chicks in Argentina are dying as a direct consequence of climate change, according to new research. Drenching rainstorms and extreme heat are killing the young birds in significant numbers. The study, conducted over 27 years, looked at climate impacts on the world’s biggest colony of Magellanic penguins, which live on the arid Punta Tombo peninsula. The research has been published in the journal Plos One. About 200,000 pairs of these penguins make their nests on the peninsula every year. […] They are too big for their parents to sit on top of and keep warm, but too young to have waterproof feathers. As a result, they are particularly vulnerable to rainstorms. If they get drenched they usually die, despite the attentions of their despairing parents. They can also succumb to extreme heat, as they cannot cool off in the water like the others. [more]

Climate change is ‘killing Argentina’s Magellanic penguin chicks’

ABSTRACT: Climate change is causing more frequent and intense storms, and climate models predict this trend will continue, potentially affecting wildlife populations. Since 1960 the number of days with >20 mm of rain increased near Punta Tombo, Argentina. Between 1983 and 2010 we followed 3496 known-age Magellanic penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) chicks at Punta Tombo to determine how weather impacted their survival. In two years, rain was the most common cause of death killing 50% and 43% of chicks. In 26 years starvation killed the most chicks. Starvation and predation were present in all years. Chicks died in storms in 13 of 28 years and in 16 of 233 storms. Storm mortality was additive; there was no relationship between the number of chicks killed in storms and the numbers that starved (P = 0.75) or that were eaten (P = 0.39). However, when more chicks died in storms, fewer chicks fledged (P = 0.05, R2 = 0.14). More chicks died when rainfall was higher and air temperature lower. Most chicks died from storms when they were 9–23 days old; the oldest chick killed in a storm was 41 days old. Storms with heavier rainfall killed older chicks as well as more chicks. Chicks up to 70 days old were killed by heat. Burrow nests mitigated storm mortality (N = 1063). The age span of chicks in the colony at any given time increased because the synchrony of egg laying decreased since 1983, lengthening the time when chicks are vulnerable to storms. Climate change that increases the frequency and intensity of storms results in more reproductive failure of Magellanic penguins, a pattern likely to apply to many species breeding in the region. Climate variability has already lowered reproductive success of Magellanic penguins and is likely undermining the resilience of many other species.

Climate Change Increases Reproductive Failure in Magellanic Penguins