Inside China’s desperate effort to control pollution, before it’s too late

By Ari Phillips

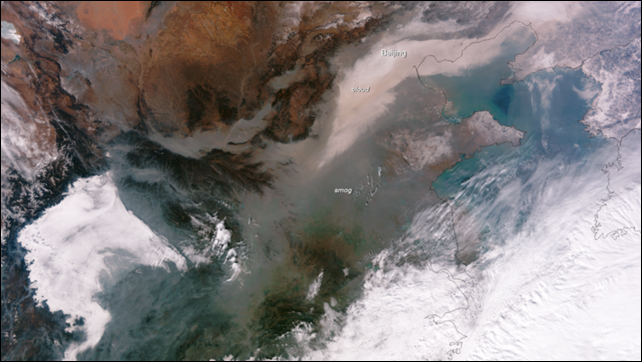

26 November 2013 (Climate Progress) – If James Carville was giving the Chinese government public relations advice, he might say something like, “It’s the pollution, stupid.” But this wouldn’t be anything the Chinese government doesn’t already know. When eight-year-olds start getting lung cancer that can be attributed to air pollution, you’ve got a problem. When smog forces schools, roads, and airports to shut down because visibility is less than 50 yards, you’ve got a problem. When a study finds that severe pollution is slashing an average of five-and-a-half years from the life expectancy in northern China, you’ve got a problem. Such a visible problem, literally, can lead to myopic responses in a frantic effort to make it appear that the problem is being confronted. For instance, last month the Chinese central government announced it will start publishing a list of its 10 worst — and best — cities for air pollution each month. But underneath all the haze, the seeds of a real transition are taking root. In July, the government said it would spend $275 billion through 2018 to reduce pollution levels around Beijing. Last month Shanghai released its Clean Air Action Plan in an effort to rapidly and substantially improve the air quality in China’s most populous city of nearly 24 million residents. The Chinese government is not stupid and neither are China’s 1.35 billion residents — they can all see that pollution is a real problem. Earlier this month, Chinese communist party leaders convened a major plenary meeting to discuss economic reform, with over 200 party members gathering at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in Beijing, or third plenum. Plenums are significant because every member of the party must be present and this year, energy and environmental issues were on the agenda. Third plenary sessions have been met with high anticipation ever since the 11th Third Plenary Session in 1978 led to the structural reforms ushered in by Deng Xiaoping and the ensuing three decades of rapid growth that have turned China into the export-driven, world power it is today. But that sustained economic boom also led to a bust for the environment. R. Edward Grumbine, a senior international scientist in the Key Lab of Biodiversity and Biogeography at Kunming Institute of Botany, wrote in Yale360 that as the 18th Plenum ended, China’s new President, Xi Jinping, and Prime Minister Li Keqiang find their country at a critical crossroads. “The economy has slowed, and China is confronting the cumulative consequences of its three-decade focus on economic expansion with little attention paid to mounting ecological and social costs,” Grumbine wrote. Grumbine thinks that the plenum may one day be seen as the turning point marking China’s shift away from unbridled economic growth to a more balanced form of development. “One thing is certain: China’s leadership is now feeling intensifying public pressure to do something about the environment. A growing number of China’s 1.35 billion people — especially those in the rapidly expanding middle class — are fed up with government inaction on environmental issues,” Grumbine wrote. Take water for instance. Half of China’s rivers — about 28,000 — have vanished since 1990. China also has about 1,730 cubic meters of fresh water per person, just above the 1,700 cubic meter-level the UN deems “stressed.” In the north, where half of China’s people, most of its coal, and only 20 percent of its water are located, the situation is even more dire. About 300 million rural residents do not have access to safe drinking water, and 57 percent of urban groundwater, a primary source of drinking water, is also polluted. Coal industries and power stations use as much as 17 percent of China’s water, and by 2020 the government plans to boost coal-fired power by twice the total generating capacity of India. According to British Petroleum (BP), China will account for 25 percent of global growth in energy demand through 2030. China’s 2012 energy mix was comprised of 68 percent coal, 18 percent oil and five percent natural gas. […] Chris Nielsen, executive director of the China Project at Harvard University, told Climate Progress in an email that the Chinese government has not simply ignored its environmental concerns and focused only on economic growth. […] “Positive changes have been overwhelmed by negative changes in many respects,” Nielsen said. “By far the most important of the negative changes is a tremendous concomitant rise in the consumption of coal to fuel the economy, which by itself cancels many of these gains.” [more]

Inside China’s Desperate Effort To Control Pollution — Before It’s Too Late

wonderful info you deserve a big bravo for that