Drowning Kiribati – ‘The ocean went back out in Hurricane Sandy, but one day it won’t. It will stay.’

By Jeffrey Goldberg

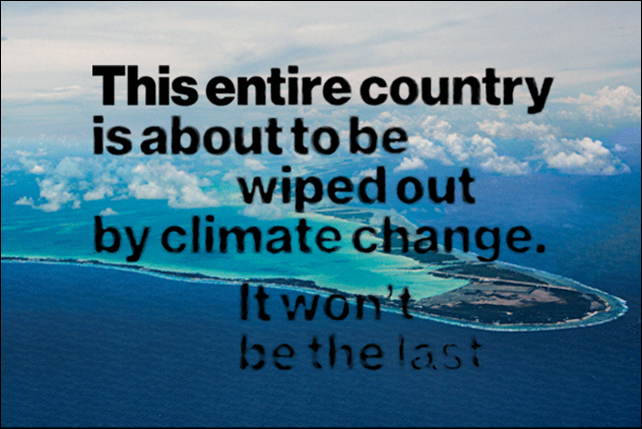

21 November 2013 (Bloomberg) – The spruce man with the trim mustache and the grim-faced bodyguard is dozing in his seat. A flight attendant leaves him a hot towel, and then another. The bodyguard, who wears the uniform of the Kiribati National Police—the shoulder patch depicts a yellow frigate bird flying clear of the rising sun—folds the towels carefully and places them on an armrest. The Fiji Airways flight is moving north across the equator to Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati. The passengers include a Japanese executive who represents important tuna interests, a Mormon luminary from Samoa and his prim wife, and an American dressed in the manner of an Iraq War contractor, on a mission to recover the remains of U.S. Marines killed in World War II. We are all impatient for the sleeping man, who is the president of Kiribati, to wake up. We each have business to transact with him. But the president sleeps. His name is Anote Tong. He is famous—or, at the very least, as famous as anyone from Kiribati has ever been—for arguing that the industrialized nations of the world are murdering his country. Kiribati is a flyspeck of a United Nations member state, a collection of 33 islands necklaced across the central Pacific. Thirty-two of the islands are low-lying atolls; the 33rd, called Banaba, is a raised coral island that long ago was strip-mined for its seabird-guano-derived phosphates. If scientists are correct, the ocean will swallow most of Kiribati before the end of the century, and perhaps much sooner than that. Water expands as it warms, and the oceans have lately received colossal quantities of melted ice. A recent study found that the oceans are absorbing heat 15 times faster than they have at any point during the past 10,000 years. Before the rising Pacific drowns these atolls, though, it will infiltrate, and irreversibly poison, their already inadequate supply of fresh water. The apocalypse could come even sooner for Kiribati if violent storms, of the sort that recently destroyed parts of the Philippines, strike its islands. For all of these reasons, the 103,000 citizens of Kiribati may soon become refugees, perhaps the first mass movement of people fleeing the consequences of global warming rather than war or famine. This is why Tong visits Fiji so frequently. He is searching for a place to move his people. The government of Kiribati (pronounced KIR-e-bass, the local variant of Gilbert, which is what these islands were called under British rule) recently bought 6,000 acres of land in Fiji for a reported $9.6 million, to the apparent consternation of Fiji’s military rulers. Fiji has expressed no interest in absorbing the I-Kiribati, as the country’s people are known. A former president of Zambia, in south-central Africa, once offered Kiribati’s people land in his country, but then he died. No one else so far has volunteered to organize a rescue. […] I explain that I’m visiting Tarawa to understand the impact of climate change on his country. He smiles. “Hurricane Sandy,” he says. I attempt to protest, saying Kiribati’s future should be of global concern, whether or not it teaches broad lessons about the climate crisis. Tong, educated at the London School of Economics and universally thought to be the savviest of the Pacific island presidents, isn’t buying it. “You want to see what happens when the ocean comes in but doesn’t go out,” he says. “The ocean went back out in Hurricane Sandy, but one day it won’t. It will stay.” [more]