Deadly brain-eating amoeba moving north as climate warms

By Elizabeth Weise

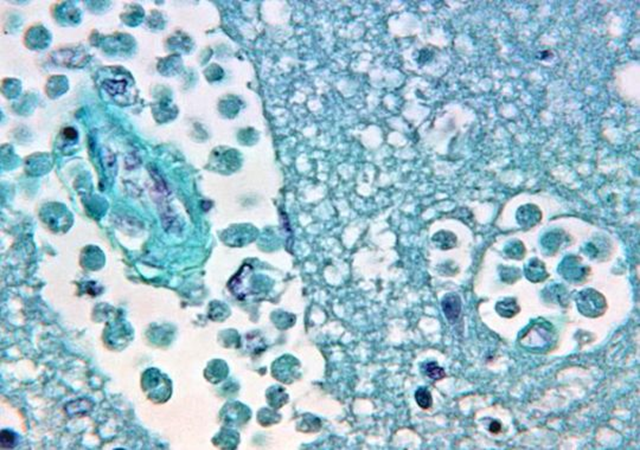

4 December 2013 (USATODAY) – Bridget Bahneman lost her daughter to an illness that wasn’t supposed to exist as far north as Minnesota. Seven-year-old Annie’s brain was destroyed by an amoeba called Naegleria fowleri that she was exposed to while swimming in a lake near their house. The “brain-eating amoeba” lives in fresh water and proliferates when temperatures reach the 80s. It infects people by entering the nose and reaching the brain. It can’t be transmitted by drinking infected water, only when it is pushed far up into the nose, often but not always from diving or wake boarding, says Jeremy Lewis of Arlington, Texas. He and his wife, Julie, founded Kyle Cares Amoeba Awareness, a non-profit organization, after they lost their son Kyle to the disease in 2010. The water in Minnesota had been too cold for Naegleria to thrive. But August 2010 was the third-warmest in Minneapolis since 1891. A summer heat wave unlike any Bahneman remembered warmed lakes and sent her husband and kids out swimming near their home in Stillwater, Minn. Annie fell ill a week later. On Monday, she mentioned she felt a little sick. On Tuesday morning, she said she had a headache. Bahneman, a nurse-midwife, did a quick neurological check, and she seemed fine. Tuesday evening, she was worse. “My husband sent me a text and said, ‘Don’t run any errands. I think you should come straight home from work. Annie’s not well,'” she said. Their oldest daughter had been running a high fever and vomiting all day. Her parents took her to urgent care, where she was diagnosed with strep throat. Bahneman worried Annie had meningitis, but the doctors didn’t think so. “They sent us home. I remember thinking, ‘I need to bring her to the hospital,’ but I didn’t want to be an alarmist.” That night, Bahneman laid down next to her daughter, so she could wake her every 30 minutes to give her water. At 6 a.m., she got up to call work and say she couldn’t come in. “When I came back, I realized she was unconscious.” They went immediately to Children’s Saint Paul Pediatric Hospital. Annie was having seizures. “Ten people went to work on her immediately,” Bahneman says. They were finally able to stabilize Annie, and on Wednesday, she was taken to the intensive care unit. Nothing the doctors did helped, and by the next day, Annie was experiencing visions and having seizures every half an hour. The infection control doctor at the hospital kept asking, “Have you been swimming in any lakes in the southern United States?” They hadn’t. Bahneman had taught her kids to sign when they were little. Annie’s last communication was with her hands, because she couldn’t talk. “She signed that she was in pain and for them to stop what they were doing.” Annie died on Saturday, Aug. 21, 2010. Bahneman and her husband, Chad, asked for an autopsy, and it was only then that they found out what had killed their firstborn. The pathologist who performed the autopsy had trained in Texas. He had seen primary amebic meningoencephalitis (the disease caused by the amoeba) once early on in his career. “During the autopsy of her brain, he said, ‘I think I know what this is,'” Bahneman says. That created a second mystery. Naegleria had never been seen before that far north. The couple ended up on an hour-and-a-half-long conference call with state and national health experts. They asked the same question over and over: “Where were you swimming? Are you sure you never left the state? Are you sure you didn’t travel?” In November, when samples from the lake Annie had swum in came back, it was confirmed: There was Naegleria fowleri in the water. A second child got it in the same lake two years later and also died. [more]

This is a terribly tragic story.

Thanks for passing this on – a timely warning in a warming world. ~Survival Acres~