The ocean is broken – ‘We hardly saw any living things. We saw one whale, sort of rolling helplessly on the surface with what looked like a big tumour on its head.’

By Greg Ray

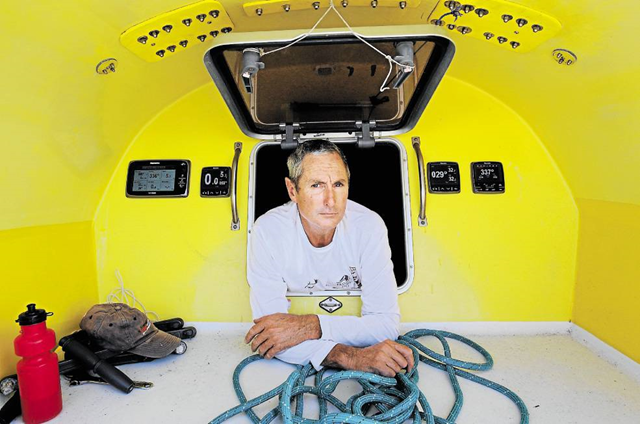

18 October 2013 (Newcastle Herald) – It was the silence that made this voyage different from all of those before it. Not the absence of sound, exactly. The wind still whipped the sails and whistled in the rigging. The waves still sloshed against the fibreglass hull. And there were plenty of other noises: muffled thuds and bumps and scrapes as the boat knocked against pieces of debris. What was missing was the cries of the seabirds which, on all previous similar voyages, had surrounded the boat. The birds were missing because the fish were missing. Exactly 10 years before, when Newcastle yachtsman Ivan Macfadyen had sailed exactly the same course from Melbourne to Osaka, all he’d had to do to catch a fish from the ocean between Brisbane and Japan was throw out a baited line. “There was not one of the 28 days on that portion of the trip when we didn’t catch a good-sized fish to cook up and eat with some rice,” Macfadyen recalled. But this time, on that whole long leg of sea journey, the total catch was two. No fish. No birds. Hardly a sign of life at all. “In years gone by I’d gotten used to all the birds and their noises,” he said. “They’d be following the boat, sometimes resting on the mast before taking off again. You’d see flocks of them wheeling over the surface of the sea in the distance, feeding on pilchards.” But in March and April this year, only silence and desolation surrounded his boat, Funnel Web, as it sped across the surface of a haunted ocean. North of the equator, up above New Guinea, the ocean-racers saw a big fishing boat working a reef in the distance. “All day it was there, trawling back and forth. It was a big ship, like a mother-ship,” he said. And all night it worked too, under bright floodlights. And in the morning Macfadyen was awoken by his crewman calling out, urgently, that the ship had launched a speedboat. “Obviously I was worried. We were unarmed and pirates are a real worry in those waters. I thought, if these guys had weapons then we were in deep trouble.” But they weren’t pirates, not in the conventional sense, at least. The speedboat came alongside and the Melanesian men aboard offered gifts of fruit and jars of jam and preserves. “And they gave us five big sugar-bags full of fish,” he said. “They were good, big fish, of all kinds. Some were fresh, but others had obviously been in the sun for a while. “We told them there was no way we could possibly use all those fish. There were just two of us, with no real place to store or keep them. They just shrugged and told us to tip them overboard. That’s what they would have done with them anyway, they said. “They told us that his was just a small fraction of one day’s by-catch. That they were only interested in tuna and to them, everything else was rubbish. It was all killed, all dumped. They just trawled that reef day and night and stripped it of every living thing.” Macfadyen felt sick to his heart. That was one fishing boat among countless more working unseen beyond the horizon, many of them doing exactly the same thing. No wonder the sea was dead. No wonder his baited lines caught nothing. There was nothing to catch. If that sounds depressing, it only got worse. The next leg of the long voyage was from Osaka to San Francisco and for most of that trip the desolation was tinged with nauseous horror and a degree of fear. “After we left Japan, it felt as if the ocean itself was dead,” Macfadyen said. “We hardly saw any living things. We saw one whale, sort of rolling helplessly on the surface with what looked like a big tumour on its head. It was pretty sickening. “I’ve done a lot of miles on the ocean in my life and I’m used to seeing turtles, dolphins, sharks and big flurries of feeding birds. But this time, for 3000 nautical miles there was nothing alive to be seen.” In place of the missing life was garbage in astounding volumes. [more]