Study links warmer water temperatures to greater levels of mercury in fish

By Darryl Fears

13 October 2013

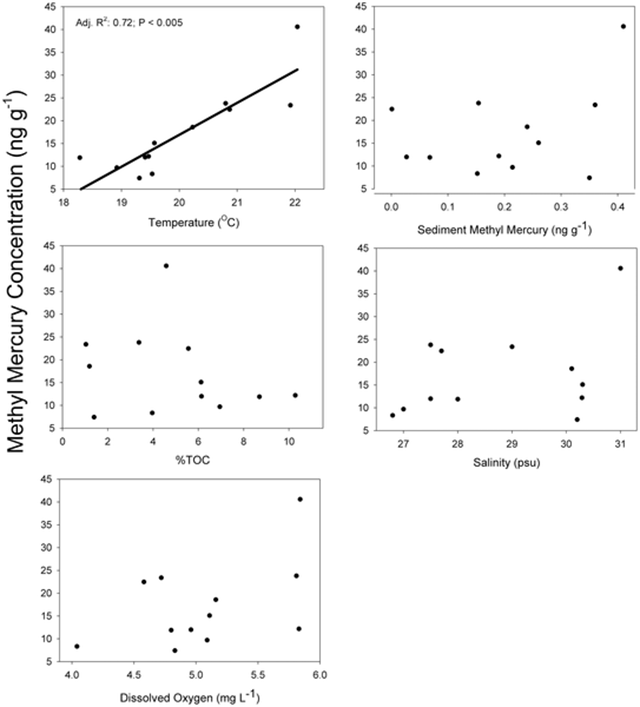

(Washington Post) – Under the watchful eyes of scientists, a little forage fish that lives off the southern coast of Maine developed a strangely large appetite. Killifish are not usually big eaters. But in warmer waters, at temperatures projected for the future by climate scientists, their metabolism — and their appetites — go up, which is not a good thing if there are toxins in their food. In a lab experiment, researchers adjusted temperatures in tanks, tainted the killifish’s food with traces of methylmercury and watched as the fish stored high concentrations of the metal in their tissue. In a field experiment in nearby salt pools, they observed as killifish in warmer pools ate their natural food and stored metal in even higher concentrations, like some toxic condiment for larger fish that would later prey on them. The observation was part of a study showing how killifish at the bottom of the food chain will probably absorb higher levels of methylmercury in an era of global warming and pass it on to larger predator fish, such as the tuna stacked in shiny little cans in the cupboards of Americans and other people the world over. “The implication is this could play out in larger fish … because their metabolic rate is also increasing,” said Celia Chen, a professor at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and one of six authors of the study. “Methylmercury isn’t easily excreted, so it stays. It suggests that there will be higher methylmercury concentrations in the fish humans eat as well.” Methylmercury is linked to high blood pressure, kidney disease and heart attacks in adults and slow neuro-behavioral development in children. A thousand tons of the contaminant drops onto oceans every year from power plant emissions, and more than 250 tons pour from the land into various waters as a result of deforestation. Top predators on land and sea have higher levels of mercury because of their prey. It is hard for any organism to release the metal, causing it to accumulate, or biomagnify, as scientists say. The study, “Experimental and Natural Warming Elevates Mercury Concentrations in Estuarine Fish,” was published in the journal PLOS One in April 2013, and officials at Dartmouth called attention to it ahead of last week’s Minamata Convention on Mercury in Japan. Delegates from 130 nations at the three-day convention that ended Friday met to sign a treaty that seeks to greatly limit emissions from coal-fired power plants from industrial nations, mining operations in Africa and other sources that pollute oceans. [more]

Study links warmer water temperatures to greater levels of mercury in fish