More than 100 scientists warn Ecuador Congress against oil development in Yasuní National Park – ‘They are not nibbling around the edges of the park anymore, but going deep into the core’

By Jeremy Hance

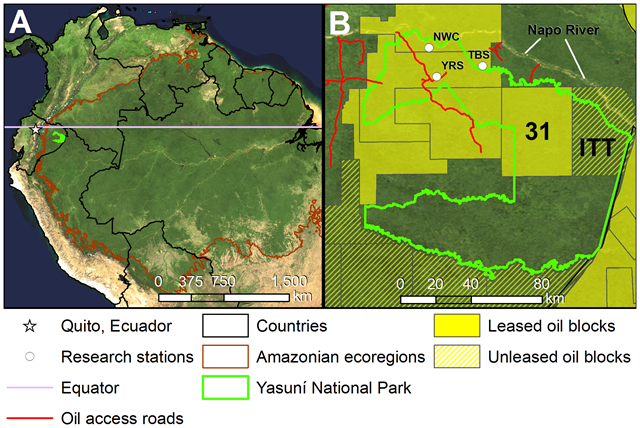

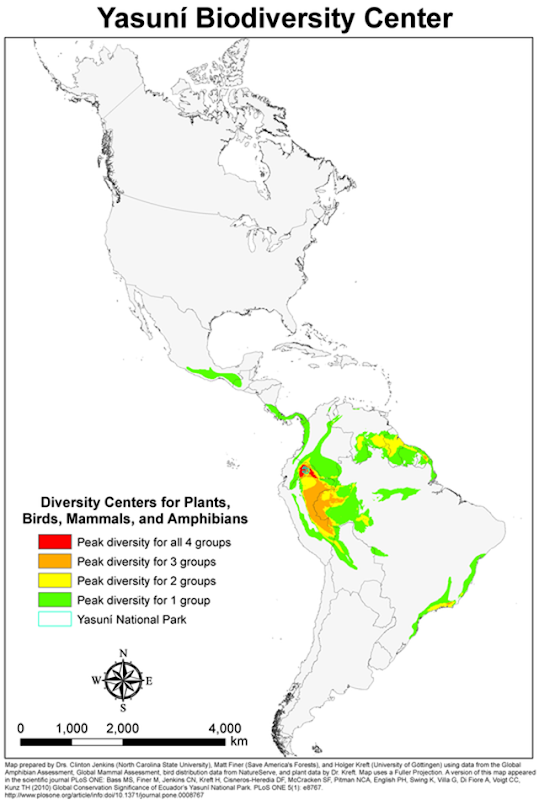

3 October 2013 (mongabay.com) – Over 100 scientists have issued a statement to the Ecuadorian Congress warning that proposed oil development and accompanying roads in Yasuní National Park will degrade its “extraordinary biodiversity.” The statement by a group dubbed the Scientists Concerned for Yasuní outlines in detail how the park is not only likely the most biodiverse ecosystems in the western hemisphere, but in the entire world. Despite this, the Ecuadorian government has recently given the go-ahead to plans to drill for oil in Yasuni’s Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) blocs, one of most remote areas in the Amazon rainforest. “Yasuní National Park may very well be the most biodiverse place in the world,” said Shawn McCracken of Texas State University. “It is a remarkable convergence of global peak diversity levels of amphibian, bird, insect, mammal, and tree species.” A landmark paper in 2010 outlined the stunning biodiversity found in Yasuní, which scientists believe is due to the collision of Amazonian and Andean ecosystems on the equator. To date, scientists have recorded 153 species of amphibians in the park—a world record for any landscape—and nearly 600 species of bird. In addition, scientists have recorded 183 species of mammals so far, over 100 of which are bats—more bats than found anywhere else in the world. Moreover the park holds the world record for the most woody plants. And that’s not even all. “A single hectare of forest in Yasuní National Park is estimated to contain at least 100,000 arthropod species, approximately the same number of insect species as is found throughout all of North America,” the scientists write in the statement. “This represents the highest estimated biodiversity per unit area in the world for any taxonomic group.” For several years, Ecuador had proposed to suspend drilling plans in the ITT blocs of Yasuní National Park, if the international community compensated it for half the expected revenue, i.e. $3.6 billion. The so-called Yasuní-ITT Initiative was seen as ground-breaking by many environmentalists, but when the revenue didn’t come fast enough—and some donors balked at details in the plan—Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa announced he was giving up the idea. At the same time, August of this year, he announced oil exploration would begin quickly in ITT. “The real dilemma is this: do we protect 100% of the Yasuní and have no resources to meet the urgent needs of our people, or do we save 99% of it and have $18 billion to defeat poverty?” Correa said in August. This announcement spurred the Scientists Concerned for Yasuní to take action once again. “The campaign is much direr this time because the government drilling plans are much more extensive than in years past,” explains Matt Finer of the Center for International Environmental Law. “They are not nibbling around the edges of the park anymore, but going deep into the core of one of the most important protected areas in the world.” [more]

Over 100 scientists warn Ecuadorian Congress against oil development in Yasuni

23 September 2013 (yasuninationalpark.org) – In 2010, scientists published the first comprehensive, peer-reviewed synthesis of biodiversity data for Yasuní National Park in the scientific journal PLoS ONE[1]. That study concluded that Yasuní has a) outstanding global conservation significance due to its extraordinary biodiversity and b) potential to sustain this biodiversity in the long term if not degraded by human activities such as oil development and accompanying roads. Here, we, the “Scientists Concerned for Yasuní,” review the principal findings from the 2010 study regarding species richness, present new information obtained in the 3.5 years since its publication, and reaffirm a set of science-based recommendations. The Scientists Concerned for Yasuní consists of more than 100 scientists from Ecuador and around the world (Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States) with experience in the park[2]. Key notes: For all text below, local scale refers to areas ≤100 km2 and landscape scale refers to areas ≤10,000 km2. Data for Yasuní National Park includes findings from the Tiputini Biodiversity Station, which is directly adjacent to the park.

Species Richness

- Yasuní National Park occupies a unique biogeographic position where species richness of four major taxonomic groups – amphibians, birds, mammals, and vascular plants – all reach diversity maxima for the Western Hemisphere (i.e., quadruple richness center, see Figure 1). For amphibians, birds, mammals, and trees, these are not just continental, but global, maxima of species richness at local scales. This relatively small quadruple richness center encompasses just 0.16% of South America and less than 0.5% of the Amazon Basin.

- The 150 amphibian species documented for Yasuní National Park in 2010 represented a world record at the landscape scale. Since publication, the number of species has risen to 153, including three newly described species. Several additional new species are currently in the process of being described.

- Adding the 121 documented reptile species, the total herpetofauna of Yasuní National Park —274 species of amphibians and reptiles—is the most diverse assemblage ever documented on a landscape scale.

- Yasuní National Park now contains at least 597 documented bird species, representing one-third of the Amazon’s total native species. The park is part of a north-south stretch of forest in the western Amazon that appears to be the richest known globally at the local scale.

- Yasuní National Park now has 176 documented mammals, adding 7 additional species of bats since the 2010 study. It is estimated that Yasuní National Park is one of the few places in the world with over 200 coexisting mammal species.

- Ten primate species (in fact, 10 genera) are confirmed to coexist near Tiputini Biodiversity Station, a remarkable diversity at the local scale. Three additional species may inhabit the park, but they are currently unconfirmed. This upper estimate of 13 monkey species approaches the richest known sites in the world.

- Yasuní National Park has among the highest local bat diversity for any site in the world, with over 100 coexisting species expected at Tiputini Biodiversity Station.

- Yasuní National Park contains 382 documented fish species, more than the entire Mississippi River Basin. The lower Yasuní River Basin, which passes through the ITT oil block, has 277 confirmed fish species. The estimated fish diversity for the park is around 500 species.

- A single hectare of forest in Yasuní National Park is estimated to contain at least 100,000 arthropod species, approximately the same number of insect species as is found throughout all of North America. This represents the highest estimated biodiversity per unit area in the world for any taxonomic group. Since 2010 nearly two dozen new species of insects have been described from Yasuní National Park.

- Yasuní National Park is among the richest areas globally for vascular plants at the landscape scale. At least 3,135 vascular plant species are currently documented, a substantial increase from the 2,700 species reported in 2010. This updated data includes over 2,300 trees and shrubs and 800 lianas, epiphytes, and ferns. Over 3,200 species are expected in the park based upon current collections.

- Yasuní National Park holds a number of global records for woody plant (trees, shrubs, and lianas) species richness at the local scale. For example, it has the highest average number of tree and shrub species per hectare of anywhere in the world. The park is part of an equatorial band of forest (stretching from the Ecuadorian Andes to Manaus in Brazil) that contains the richest 1-hectare tree plots in the world.

- A typical hectare of terra firme forest in Yasuní National Park contains at least 655 tree species, more than are native to the continental United States and Canada combined, and over 900 plant species overall.

- Yasuní National Park 50-hectare Forest Dynamics Plot update: In 2010, the plot had over 1,100 species-level taxa of trees and shrubs in the first 25 hectares. With the census completion of an additional 25 hectares, a conservative estimate of the current number of documented species is ~1,150. Over 30 new species of trees, including two new genera, have been described from the plot. Four of the new species and both new genera have been described since 2010. Additional new species await formal description.

- Specifically regarding lianas (woody climbers), 350 species have been documented in 14 hectares of censused plots in the park, more than double the amount of species reported in 2010. Just one hectare contains an average of 200 liana species. Liana biologists estimate that the park is home to around 550 species in total.

Threatened Species and Endemism

- Yasuní National Park is home to 28 Threatened or Near Threatened vertebrate species, such as White-bellied Spider Monkey, Giant Otter, Poeppig’s Woolly Monkey, Amazonian Manatee, Lowland Tapir, Giant Armadillo, and Harpy Eagle[3]. Nearly half of these 28 species are facing a high to extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

- Oil-related activities and contamination may impact the Giant Otter and Amazonian Manatee, two Threatened large aquatic mammals. Both species have been documented in the Tiputini and Yasuní Rivers, which would likely be the principal access routes and infrastructure sites for oil development in ITT and Block 31.

- Yasuní National Park is likely home to over 100 Threatened or Near Threatened plant species. Over half of these species are facing a high to extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

- Yasuní National Park is home to 43 vertebrate species that are regional endemics (i.e. endemic to the Napo Moist Forests ecoregion), including 2 monkeys, 19 birds, and 20 amphibians.

- Yasuní National Park is likely home to hundreds of plant species that are regional endemics.

Conclusion

In 2010, the authors of the PLoS ONE study generated a number of science-based policy recommendations, including:

- Permit no new roads nor other transportation access routes—such as new oil access roads, train rails, canals, and extensions of existing roads—within Yasuní National Park or its buffer zone;

- Permit no new oil exploration or development projects in Yasuní, particularly in the remote and relatively intact Block 31 and ITT Block.

- Establish a protected corridor between Yasuní and Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve that, together with the Peruvian reserves, would form a trans-boundary mega-reserve with Yasuní National Park at its core.

Here, we, the “Scientists Concerned for Yasuní”, reaffirm these recommendations. The Scientists Concerned for Yasuní consists of more than 100 scientists from Ecuador and around the world (Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States). [1] Bass MS, Finer M, Jenkins CN, Kreft H, Cisneros-Heredia DF, et al. (2010) Global Conservation Significance of Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park. PLoS ONE 5(1): e8767. http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0008767 [2] To contact the Scientists Concerned for Yasuní, write to Matt Finer (matt.finer@gmail.com) and Shawn McCracken (frocga@gmail.com) [3] Ateles belzebuth, Pteronura brasiliensis, Lagothrix poeppigii, Trichechus inunguis,Tapirus terrestris, Priodontes maximus, and Harpia harpyja, respectively.

Scientists Concerned for Yasuní – Revised Statement on Biodiversity of Yasuní National Park