Massive mine proposal threatens half of sockeye salmon runs – ‘The record of industrializing a salmon drainage is very clear: When that happens you end up losing the salmon at some point’

By Aaron Kase

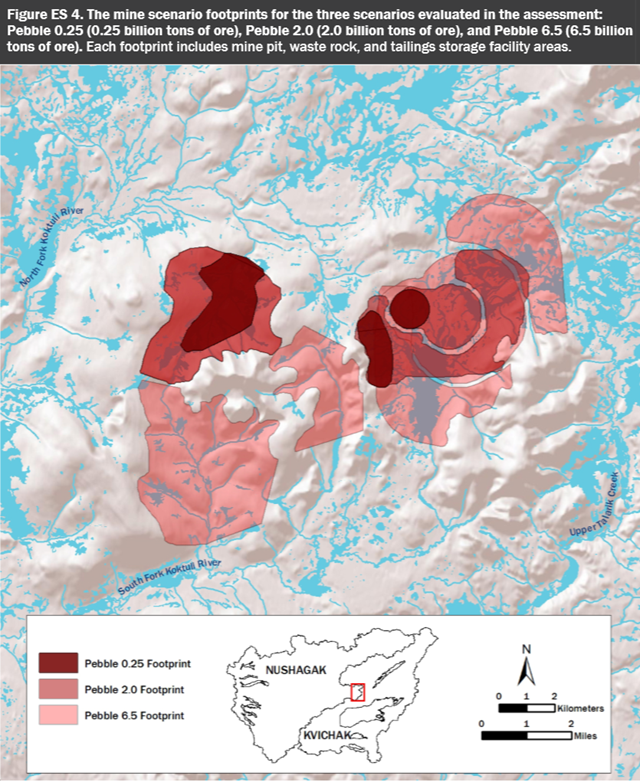

20 June 2013 (Salon) – The habitat for half the world supply of wild sockeye salmon — as well as a critical area for other wildlife, tourism and native peoples — is at urgent risk of being filled with pollutants, and sterilized in the name of gold and copper mining. Dillingham is a town of about 2,300 people, perched on an outlet into Bristol Bay, a body of water set between Alaska’s southwest coast and the Aleutian islands. The only way in or out is by boat or airplane. The town’s economy, and that of almost every settlement along the bay, relies on the thriving salmon population that returns each year to source rivers and streams to spawn. The fish productivity, and in turn the entire lifestyle of southwest Alaska, is hanging in jeopardy under the looming threat of Pebble Mine. The proposed copper and gold site is projected to be the largest open pit mine in North America and would have a devastating impact on the habitat for salmon and other wildlife. Verner Wilson III’s first memory is of trying to save a fish. The Yup’ik Eskimo, who grew up in Dillingham, Alaska, remembers visiting his family’s fishing camp when he was little. “I saw all of these fish wriggling around on the beach,” he says. “I tried to save one, take it and put it back in the water.” His grandmother stopped him, explaining that the fish were the family’s food and livelihood. “I’ve been fishing ever since,” says Wilson, now 27. Now Wilson is trying to save a lot of fish. Representing the World Wildlife Fund, he has been traveling the state and all the way to Washington, D.C., to rally opposition to the mine, while an unlikely coalition of commercial, subsistence, and sport fishermen alongside environmentalists and native tribes has mobilized to preserve one of the last great salmon fisheries left in the world. “Every single piece of the economy here is tied into fishing one way or another,” says Katherine Carscallen, who also grew up in a Dillingham fishing family. “It’s our livelihood and lifestyle that would be completely erased if this mine went through.” […] If Pebble Mine ever breaks ground, even the best case scenario looks dire. The EPA recently released a draft report [pdf] that makes the stakes clear: Construction and support of the mine would require an immense amount of infrastructure across land scarcely touched by human hands, from roads to culverts to energy sources to pipelines to a containment dam to hold back toxic mine waste. The development would sit at the headwaters of the Kvichak and Nushagak rivers, damaging two of the nine main feeder sources to Bristol Bay and eliminating at least 90 miles of stream habitat and thousands of acres of protective wetlands. […] “We know that acid mine draining will happen at this mine,” says David Chambers, a Ph.D. in physical engineering who works for the Center for Science and Public Participation. “The real issue is can you mitigate it or not.” Copper is notorious for interfering with fish’s sense of smell, which could make it impossible to find their way back to the natal stream, or prevent baby salmon from detecting and avoiding predators. Enough copper, sulphides, or other minerals in the water could also kill the fish outright. All that waste would be held back behind an enormous dam in a tectonically active area. Fifty years or more down the road, when the mine is empty of useful minerals and abandoned, the dam will still stand, expected to contain a deadly mix of chemicals in perpetuity, a ticking time bomb in an earthquake-prone area. What’s more, once one mine and its infrastructure is in place, more are sure to follow. “The record of industrializing a salmon drainage is very clear,” Chambers says. “When that happens you end up losing the salmon at some point.” [more]