Study finds alarming declines in U.S. amphibians, even in protected areas – Many species will disappear from half of habitats in 20 years

By Timothy B. Wheeler

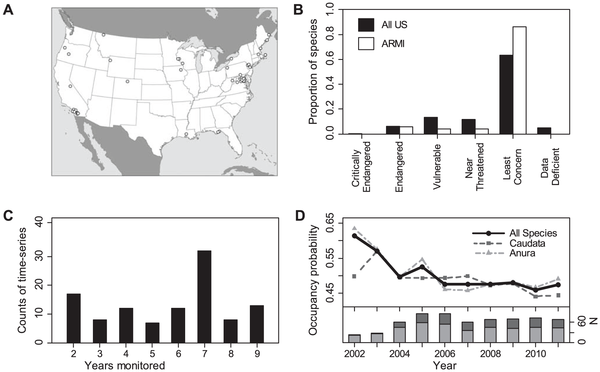

22 May 2013 (The Baltimore Sun) – Some of springtime’s more notable heralds appear to be fading away, as a new study finds frogs, toads and salamanders disappearing at an alarming rate across the United States. In what they say is the first analysis of its kind, scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey and a couple of universities report that declines in environmentally sensitive amphibians are more widespread and more severe than previously thought. Even the most common critters, such as the spring peepers that make Maryland marshes ring with their mating cries, appear to be losing ground. What’s more, they also seem to be vanishing from ponds, streams, wetlands, and other supposedly protected habitat in national parks and wildlife refuges. “What we found was a little surprising,” said Evan Grant, a USGS wildlife biologist and study co-author who monitors amphibians in the Northeast. If the trend continues, the researchers say, some of the rarer amphibians could disappear in as few as six years from roughly half the sites where they’re now found, while the more common species could see similar declines in 26 years. Researchers have known for some time that some frog, toad and salamander species were in trouble, but until now they hadn’t developed a broad national picture of how fast they were disappearing. Besides fascinating children of all ages, amphibians help control mosquitoes and other insect pests. They’re also important sentinels for changes in the environment, because they spend part of their lives in water and part on land. They’re cold-blooded, depending on the sun’s warmth to stay active, and breathe through their skin, which makes them sensitive to changes in water quality. “Amphibians are a good indicator of what’s going on,” said Joel Snodgrass, a professor and chairman of biology at Towson University. He’s seen declines locally, which he attributed mainly to development eliminating or altering their habitat, but noted that such observations are limited because of the innate elusiveness of creatures that tend to lurk in water or under rocks. The value of the USGS study, he said, is that it accounted for variability in sightings by making repeated checks over many locations and a long period. Researchers hadn’t expected to see declines in many of the more common species that they looked and listened for over nine years at nearly three dozen sites around the country, including Patuxent Research Refuge in Laurel and along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal in the Washington area. Based on earlier studies that indicated perhaps one-third of the nation’s species were losing ground, researchers had expected to find some species improving while others faced trouble. But looking at results for 48 species across all the sites, the study charted a “consistently negative” trend in how often they were found where they normally live. On average, the number of locations where amphibians could be found shrank by 3.7 percent per year, meaning that if that continued, they would be in half as many places in about 20 years. “We don’t know how long it’s been going on or whether it’s a trend that will continue,” said Michael Adams, the study’s lead author and USGS research ecologist in Oregon. The study did not attempt to identify the cause or causes for the declines. Amphibian losses have been linked previously with development, disease, chemical contaminants, climate change and even introduced species. While a fungal disease blamed for frog die-offs in other countries is found in the United States, Adams said, “we’re not seeing patterns that would help us make that link.” The researchers limited their monitoring to sites controlled by the U.S. Department of the Interior, so development likely had little direct impact on the amphibians’ habitat. “The fact we see declines even in protected areas means there is some larger-scale issue going on with amphibian populations,” Grant said. Parts of the nation experienced severe but not unprecedented drought during the study, the researchers noted, which might have reduced the amount of rain sustaining their wetlands and ponds. In Maryland, state biologists say that with a few exceptions they have not seen drastic declines in the past 20 years or so in the 20 species of frogs and toads or in the 21 species of salamanders and newts found in the state. Glenn Therres, a wildlife biologist with the Department of Natural Resources who oversees an annual volunteer-driven census of the state’s amphibians and reptiles, noted that there has not been any systematic sampling done for most of the state’s species, so it’s hard to draw overarching conclusions. But Scott Stranko, a DNR biologist who oversees an ongoing statewide survey of Maryland streams, said it has tracked declines in some of the salamanders more sensitive to disturbances in landscape or water quality. “It’s pretty conclusive that where you have urban development you lose salamanders and probably some frogs as well,” said Mark Southerland, a private consulting ecologist who has worked with DNR on the stream survey. The Northern two-lined salamander, for instance, appears to be pretty tolerant of changes to its habitat, so it is still found pretty widely, he said. But other apparently more sensitive species show up less often. Another factor likely contributing to amphibian declines in urbanized areas such as Baltimore is the widespread use of salt to keep roads clear of ice and snow, Snodgrass said. Changes in salinity can kill the freshwater aquatic insects on which salamanders and frogs feed. And the salt also poses a direct threat to amphibians. Because they breathe through their skin, increases in water salinity can cause them to lose vital fluid from their bodies. “Basically, they die of thirst in an aquatic environment,” Snodgrass said.

Alarming declines seen in frogs, salamanders

Contact Information: Catherine Puckett

, Phone: 352-377-2469

U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey

Office of Communications and Publishing

12201 Sunrise Valley Dr, MS 119

Reston, VA 20192 CORVALLIS, Oregon, 22 May 2013 – The first-ever estimate of how fast frogs, toads, and salamanders in the United States are disappearing from their habitats reveals they are vanishing at an alarming and rapid rate. According to the study released today in the scientific journal PLOS ONE, even the species of amphibians presumed to be relatively stable and widespread are declining. And these declines are occurring in amphibian populations everywhere, from the swamps in Louisiana and Florida to the high mountains of the Sierras and the Rockies. The study by USGS scientists and collaborators concluded that U.S. amphibian declines may be more widespread and severe than previously realized, and that significant declines are notably occurring even in protected national parks and wildlife refuges. “Amphibians have been a constant presence in our planet’s ponds, streams, lakes and rivers for 350 million years or so, surviving countless changes that caused many other groups of animals to go extinct,” said USGS Director Suzette Kimball. “This is why the findings of this study are so noteworthy; they demonstrate that the pressures amphibians now face exceed the ability of many of these survivors to cope.” On average, populations of all amphibians examined vanished from habitats at a rate of 3.7 percent each year. If the rate observed is representative and remains unchanged, these species would disappear from half of the habitats they currently occupy in about 20 years. The more threatened species, considered “Red-Listed” in an assessment by the global organization International Union for Conservation of Nature, disappeared from their studied habitats at a rate of 11.6 percent each year. If the rate observed is representative and remains unchanged, these Red-Listed species would disappear from half of the habitats they currently occupy in about six years. “Even though these declines seem small on the surface, they are not,” said USGS ecologist Michael Adams, the lead author of the study. “Small numbers build up to dramatic declines with time. We knew there was a big problem with amphibians, but these numbers are both surprising and of significant concern.” For nine years, researchers looked at the rate of change in the number of ponds, lakes and other habitat features that amphibians occupied. In lay terms, this means that scientists documented how fast clusters of amphibians are disappearing across the landscape. In all, scientists analyzed nine years of data from 34 sites spanning 48 species. The analysis did not evaluate causes of declines. The research was done under the auspices of the USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative, which studies amphibian trends and causes of decline. This unique program, known as ARMI, conducts research to address local information needs in a way that can be compared across studies to provide analyses of regional and national trends. Brian Gratwicke, amphibian conservation biologist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, said, “This is the culmination of an incredible sampling effort and cutting-edge analysis pioneered by the USGS, but it is very bad news for amphibians. Now, more than ever, we need to confront amphibian declines in the U.S. and take actions to conserve our incredible frog and salamander biodiversity.” The study offered other surprising insights. For example, declines occurred even in lands managed for conservation of natural resources, such as national parks and national wildlife refuges. “The declines of amphibians in these protected areas are particularly worrisome because they suggest that some stressors – such as diseases, contaminants and drought – transcend landscapes,” Adams said. “The fact that amphibian declines are occurring in our most protected areas adds weight to the hypothesis that this is a global phenomenon with implications for managers of all kinds of landscapes, even protected ones.” Amphibians seem to be experiencing the worst declines documented among vertebrates, but all major groups of animals associated with freshwater are having problems, according to Adams. While habitat loss is a factor in some areas, other research suggests that things like disease, invasive species, contaminants and perhaps other unknown factors are related to declines in protected areas. “This study,” said Adams, “gives us a point of reference that will enable us to track what’s happening in a way that wasn’t possible before.” Read FAQs about this research The publication, Trends in amphibian occupancy in the United States, is authored by Adams, M.J., Miller, D.A., Muths, E., Corn, P.S., Campbell Grant, E.H., Bailey, L., Fellers, G.M., Fisher, R.N., Sadinski, W.J., Waddle, H., and Walls, S.C., and is available to the public. Read a USGS blog, Front-row seats to climate change, about 3 other recent USGS amphibian studies. For more information about USGS amphibian research, visit http://armi.usgs.gov/

USGS Study Confirms U.S. Amphibian Populations Declining at Precipitous Rates