China vastly under-reports global fish catch – ‘We’re looking at decimation in the next decade’

By Gwynn Guilford

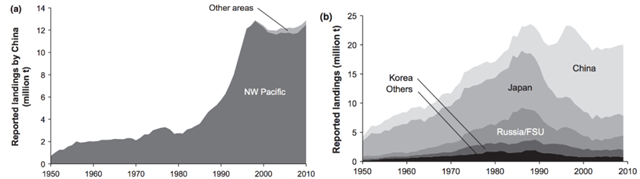

30 April 2013 (The Atlantic) – China might be cracking down on luxury spending in watches, cars, banquets and really foul liquor. But the market for pricey fish parts continues relatively unabated. US border officials recently busted a ring smuggling bladders of an endangered fish used for medicinal Chinese soups (here are some images of these prized bladders). The amount of bladders they seized could have sold for more than $3.6 million, said prosecutors. And there are many other smuggling rings out there. The totoaba, which is native to the Gulf of California, can grow to six feet long and live up to 25 years. Chinese medicine prizes a tubular organ that regulates the totoabas’ buoyancy; the bladder, of sorts, is thought to help promote fertility. According to one report, a similar fish native to Chinese waters called a bahaba, which is also coveted for its bladder, has been known to fetch as much as 3 million RMB ($487,000) per fish — and there’s plenty of evidence of a thriving black market even though it’s nearly extinct and listed by the Chinese government as a “protected species” (links in Chinese). The delicacy that comes from shark fins is far better known than totoaba-bladder soup. And though shark fins are now synonymous with luxury — shark-fin soup can cost around $100 a pop — they too are thought to help stimulate blood flow and cure cancer, among other things. As a result of this trade, nearly 100 million sharks are killed each year, say scientists. That’s 6.4 percent to 7.9 percent of the shark population each year — which means they’re being killed faster than the rate at which they reproduce. Below are all the countries that export shark fins to Hong Kong, which imported some 10.3 million kilograms of shark fins in 2011. […] The black market for manta rays that has encouraged rampant plundering may soon threaten the country’s tourism — one of its main industries — since its mantas are a major diving attraction. One of Mozambique top diving areas, Inhambane, has one of the world’s biggest manta populations. And in the last 10 years, the manta’s numbers there have thinned by 87 percent, say scientists. “We’re looking at decimation in the next decade or decade-and-a-half. Manta rays are in big trouble along the coastline,” Andrea Marshall, director of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, told the Guardian. “If current trends continue, I don’t give this population more than a few generations.” […] China is dramatically under-reporting what it’s taking from the world’s seas. The average it told the UN Food and Agriculture Organization over the last decade was 368,000 tons each year. A recent European Parliament report puts that number at 4.6 million tons — some 12.5 times more than what China reported. Here’s a look at that, with the waters where it says it’s “landing” fish:

[more]

China Is Plundering the Planet’s Seas via Wit’s End

18 April 2013 (Asia Sentinel) – China is massively under-reporting the catch of its distant-waters fishing fleet, according to a little-noticed 2012 report to the European Parliament. The catch was reported to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization as averaging 368,000 tonnes of fish from distant-water fleets per year over the past decade. It was actually more than 12 times as big, at 4.6 million tonnes, according to the 102-page report, titled The Role of China in World Fisheries. The study focuses on marine capture fisheries (excluding aquaculture and inland fisheries) and deals with mainland China. Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan are excluded. It is based on a specifically assembled, large international database of reported occurrences of Chinese vessels in various parts of the world, and related information, the authors say. It does note that China has “significantly improved its cooperation track record in recent years, particularly within the Regional Fisheries Management Organizations” although the country frequently opposes changes to regulatory rules. “In any case, China’s fisheries agreements are characterized by lack of transparency and, quite often, controversial content.” The report comes at a time when marine scientists are expressing growing alarm about overfishing, which is denuding the world’s oceans. According to the FAO, 52 percent of global fish stocks are fully exploited, 20 percent are moderately exploited, 17 percent are depleted and 1 percent is recovering. That means a quarter of the world’s fish stocks are overexploited or depleted, with 52 percent fully exploited and in danger of being overexploited and collapsing. For instance, the cod fishery off the eastern coast of North America, once the most abundant in the world, completely collapsed in 1992 and although commercial fishing has been banned, the stocks remain depleted. Some 40,000 people working in the industry lost their jobs. As a result of the depletion of ocean stocks, aquaculture – farmed fish – in 2009 surpassed wild catch for the first time and continues to grow rapidly although that causes a growing strain on marine resources, according to the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) because farmed fish are fed from wild catch. There are also numerous environmental problems from farmed fish. Unreported or unregulated catches around the Africa region show that around 2.5 million tonnes per year of the estimated Chinese distant water catch of about 3.1 million tonnes per year in the African region, may be unreported. Similarly, the disposition of the catch remains unclear, though there is evidence that some of it ends up on international markets, notably in the European Union, the report notes. The authors called the excess fishing capacity “the major impediment to the effective management of marine resources in China, generally suffering from over-exploitation. However, the strategies to reduce fleet capacity have had limited success so far in a highly-decentralized system where the registration of fishing vessels is handled by regional offices.” [more]

China Vastly Under-Reports Global Fish Catch