Scientists find Antarctic ice is melting faster – Summer ice melt has been 10 times more intense over the past 50 years compared with 600 years ago

By James Grubel; Editing by Paul Tait

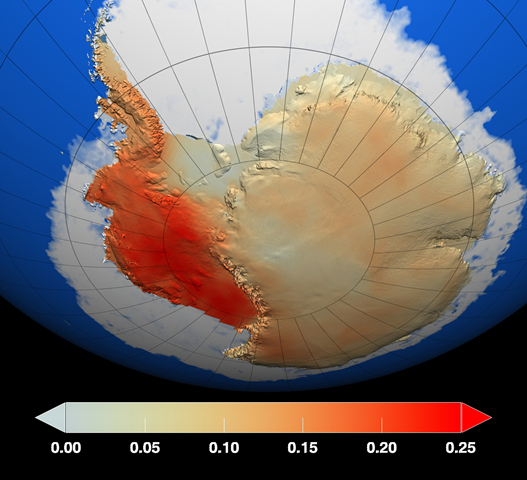

15 April 2013 CANBERRA (Reuters) – The summer ice melt in parts of Antarctica is at its highest level in 1,000 years, Australian and British researchers reported on Monday, adding new evidence of the impact of global warming on sensitive Antarctic glaciers and ice shelves. Researchers from the Australian National University and the British Antarctic Survey found data taken from an ice core also shows the summer ice melt has been 10 times more intense over the past 50 years compared with 600 years ago. “It’s definitely evidence that the climate and the environment is changing in this part of Antarctica,” lead researcher Nerilie Abram said. Abram and her team drilled a 364-metre (400-yard) deep ice core on James Ross Island, near the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, to measure historical temperatures and compare them with summer ice melt levels in the area. They found that, while the temperatures have gradually increased by 1.6 degrees Celsius (2.9 degrees Fahrenheit) over 600 years, the rate of ice melting has been most intense over the past 50 years. That shows the ice melt can increase dramatically in climate terms once temperatures hit a tipping point. “Once your climate is at that level where it is starting to go above zero degrees, the amount of melt that will happen is very sensitive to any further increase in temperature you may have,” Abram said. Robert Mulvaney, from the British Antarctic Survey, said the stronger ice melts are likely responsible for faster glacier ice loss and some of the dramatic collapses from the Antarctic ice shelf over the past 50 years. Their research was published in the Nature Geoscience journal.

Scientists find Antarctic ice is melting faster

15 April 2013 (Press Association) – Summer ice is melting at a faster rate in the Antarctic peninsula than at any time in the last 1,000 years, new research has shown.

The evidence comes from a 364-metre ice core containing a record of freezing and melting over the previous millennium. Layers of ice in the core, drilled from James Ross Island near the northern tip of the peninsula, indicate periods when summer snow on the ice cap thawed and then refroze. By measuring the thickness of these layers, scientists were able to match the history of melting with changes in temperature. Lead researcher Dr Nerilie Abram, from the Australian National University and British Antarctic Survey (BAS), said: “We found that the coolest conditions on the Antarctic peninsula and the lowest amount of summer melt occurred around 600 years ago. “At that time temperatures were around 1.6C lower than those recorded in the late 20th century and the amount of annual snowfall that melted and refroze was about 0.5%. “Today, we see almost 10 times as much (5%) of the annual snowfall melting each year. “Summer melting at the ice core site today is now at a level that is higher than at any other time over the last 1,000 years. And while temperatures at this site increased gradually in phases over many hundreds of years, most of the intensification of melting has happened since the mid-20th century.” Levels of ice melt on the Antarctic peninsula were especially sensitive to rising temperature during the last century, he said. “What that means is that the Antarctic peninsula has warmed to a level where even small increases in temperature can now lead to a big increase in summer melt,” Abram added. Dr Robert Mulvaney, from the British Antarctic Survey, who led the ice core drilling expedition in 2008 and co-authored a paper on the findings published on Sunday in the journal Nature Geoscience. He said: “Having a record of previous melt intensity for the Peninsula is particularly important because of the glacier retreat and ice shelf loss we are now seeing in the area. “Summer ice melt is a key process that is thought to have weakened ice shelves along the Antarctic peninsula leading to a succession of dramatic collapses, as well as speeding up glacier ice loss across the region over the last 50 years.” [more]