Record-sized Lake Erie algae bloom of 2011 likely to become regular occurrence, study says – ‘Everything is trending in the direction of conditions conducive to more large blooms’

By John Mangels

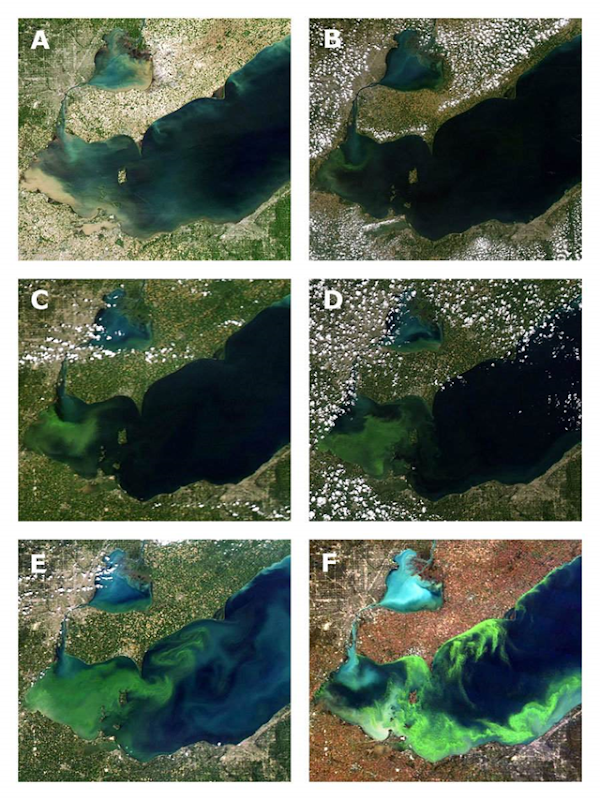

1 April 2013 (The Plain Dealer) – The record-shattering glut of toxic algae that fouled much of Lake Erie in 2011 wasn’t a fluke, but a sign of what’s likely ahead for the troubled lake, researchers say. A combination of weather extremes and long-standing farming practices that unwittingly aid algae growth spawned the 2011 mega-bloom, a team of Midwest scientists who spent months examining the phenomenon reported Monday. At its peak, the bright green layer of scum on the lake covered six times the area of New York City, and was so thick in spots that it hampered motor boats. The algae bloom fed on tons of phosphorus fertilizer that drenching spring storms washed from farm fields. Its explosive growth was nurtured by unusually calm, tepid lake waters. Earth’s warming climate probably will increase the occurrence of those extreme weather conditions in the Lake Erie region, according to computer models. Agricultural and environmental policies are favoring crops that require more fertilizer, as well as encouraging application methods that make it vulnerable to runoff , the researchers found. That doesn’t bode well for Lake Erie, which can expect to endure repeats of the 2011 algae surge, the scientists concluded. “Everything [is] trending in the direction of conditions conducive to more large blooms,” said Carnegie Institution for Science environmental scientist Anna Michalak, the lead author of the study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Without action, giant summertime algae slicks “may become the norm, in which case the ecosystem of Lake Erie will suffer incredibly,” said University of Toledo ecologist Thomas Bridgeman, a co-author of the study. The algae blooms pollute drinking water used by millions of people in the United State and Canada, create vast oxygen-starved dead zones that harm fish, discourage swimmers, anglers and boaters, and drive down lakefront property values. Cleveland, whose water supply comes from Lake Erie, spends an extra $5,500 per day on treatment chemicals when a bloom is present, according to the city’s water department. “We have to respond if we want a lake that serves us as a valuable natural resource,” Bridgeman said. But corrective steps won’t be easy, because of the scope and complexity of the problem, said noted climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Earth System Science Center. “It would involve both fighting climate change – an issue that requires policy action at the national and international level – and doing something about agricultural water pollution,” said Mann, who was not involved in the study. Large seasonal blooms of blue-green algae – which actually are colonies of bacteria that consume water-borne nutrients and get their energy from photosynthesis – haven’t been unusual in Lake Erie’s recent history. […] Law changes including the 1972 Clean Water Act aimed at reducing industrial and municipal water pollution greatly improved Lake Erie’s water quality during the next two decades. But algae began to build up again in the lake starting in the mid-1990s. Though scientists had been monitoring those events, they weren’t prepared for the extent of the algae onslaught of 2011. “The sheer magnitude of the bloom … caught everyone off guard,” Michalak said. It was more than three times bigger than the previous record bloom in 2008. [more]

Record-sized Lake Erie algae bloom of 2011 may become regular occurrence, study says