Recent global heat spike unlike anything in 11,000 years – ‘We’ve never seen something this rapid. Even in the ice age the global temperature never changed this quickly.’

By SETH BORENSTEIN

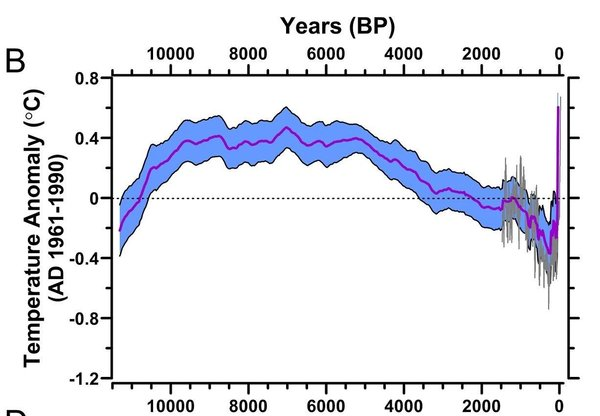

8 March 2013 WASHINGTON (AP) – A new study looking at 11,000 years of climate temperatures shows the world in the middle of a dramatic U-turn, lurching from near-record cooling to a heat spike. Research released Thursday in the journal Science uses fossils of tiny marine organisms to reconstruct global temperatures back to the end of the last ice age. It shows how the globe for several thousands of years was cooling until an unprecedented reversal in the 20th century. Scientists say it is further evidence that modern-day global warming isn’t natural, but the result of rising carbon dioxide emissions that have rapidly grown since the Industrial Revolution began roughly 250 years ago.

The decade of 1900 to 1910 was one of the coolest in the past 11,300 years — cooler than 95 percent of the other years, the marine fossil data suggest. Yet 100 years later, the decade of 2000 to 2010 was one of the warmest, said study lead author Shaun Marcott of Oregon State University. Global thermometer records only go back to 1880, and those show the last decade was the hottest for this more recent time period. “In 100 years, we’ve gone from the cold end of the spectrum to the warm end of the spectrum,” Marcott said. “We’ve never seen something this rapid. Even in the ice age the global temperature never changed this quickly.” Using fossils from all over the world, Marcott presents the longest continuous record of Earth’s average temperature. One of his co-authors last year used the same method to look even farther back. This study fills in the crucial post-ice age time during early human civilization. Marcott’s data indicates that it took 4,000 years for the world to warm about 1.25 degrees from the end of the ice age to about 7,000 years ago. The same fossil-based data suggest a similar level of warming occurring in just one generation: from the 1920s to the 1940s. Actual thermometer records don’t show the rise from the 1920s to the 1940s was quite that big and Marcott said for such recent time periods it is better to use actual thermometer readings than his proxies. Before this study, continuous temperature record reconstruction only went back about 2,000 years. The temperature trend produces a line shaped like a “hockey stick” with a sudden spike after what had been a fairly steady line. That data came from tree rings, ice cores and lake sediments. Marcott wanted to go farther back, to the end of the last ice age in more detail by using the same marine fossil method his colleague used. That period also coincides with a “really important time for the history of our planet,” said Smithsonian Institution research anthropologist Torben Rick. That’s the time when people started to first domesticate animals and start agriculture, which is connected to the end of the ice age. Marcott’s research finds the climate had been gently warming out of the ice age with a slow cooling that started about 6,000 years ago. Then the cooling reversed with a vengeance. The study shows the recent heat spike “has no precedent as far back as we can go with any confidence, 11,000 years arguably,” said Pennsylvania State University professor Michael Mann, who wrote the original hockey stick study but wasn’t part of this research. He said scientists may have to go back 125,000 years to find warmer temperatures potentially rivaling today’s. [more]

Recent heat spike unlike anything in 11,000 years

By John Roach, Contributing Writer, NBC News

7 March 2013 (NBC News) – Temperatures are rising faster today than they have at any point since at least the end of the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago, according to a new study. The finding is based on a global reconstruction of temperature records inferred from ice cores, fossils in ocean sediments and other sources. While previous studies reached similar conclusions, they covered only about 2,000 years. The new reconstruction extends the global record through the Holocene, the most recent geologic epoch. “Another way to think of it is the period where human civilization was born, created, and developed and then progressed to where we are now,” Shuan Marcott, a climate scientist at Oregon State University who led the study, told NBC News. In that time humans discovered bread and beer, learned to farm, cobbled together cities, linked them together in a web of global trade, fought wars, and, in the last 100 years or so, burned mountains of fossil fuels that filled the atmosphere with carbon dioxide, a heat trapping gas. As the fossil fuel-burning ratcheted up, the global temperatures rose 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit. That rise, Marcott said, “Is unprecedented compared to what we are showing in our reconstruction.” The reconstruction paints a picture of Earth gradually warming during the first half of the Holocene, and then, about 5,000 years ago, temperatures steadily dip to the coldest period of the Little Ice Age, about 200 years ago. Over these 5,000 years, the planet cooled 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit. This gradual rise and fall of global temperatures are governed by Earth’s orbital position relative to the sun, Marcott explained. Other studies attribute the warming since 1950 to human activity. Overall, Marcott and colleagues note Thursday in the journal Science, the planet today is warmer than it has been for about 75 percent of the Holocene. Given the rate of warming projected by climate models, the planet will be warmer by 2100 than at any point since at least the last ice age. Michael Mann is a climate scientist at Pennsylvania State University whose 1,000-year global temperature reconstruction published in 1999 resulted in the iconic “hockey stick” graph that shows the unprecedented warmth of the past century. He said the new reconstruction is “important.” “The real issue, from a climate change impacts point of view, is the rate of change — because that’s what challenges our adaptive capacity,” he said in a statement to NBC News. “And this paper suggests that the current rate has no precedent as far back as we can go with any confidence.” [more]