In drought ravaged U.S. plains, efforts to save a vital aquifer

By Jim Malewitz, Staff Writer

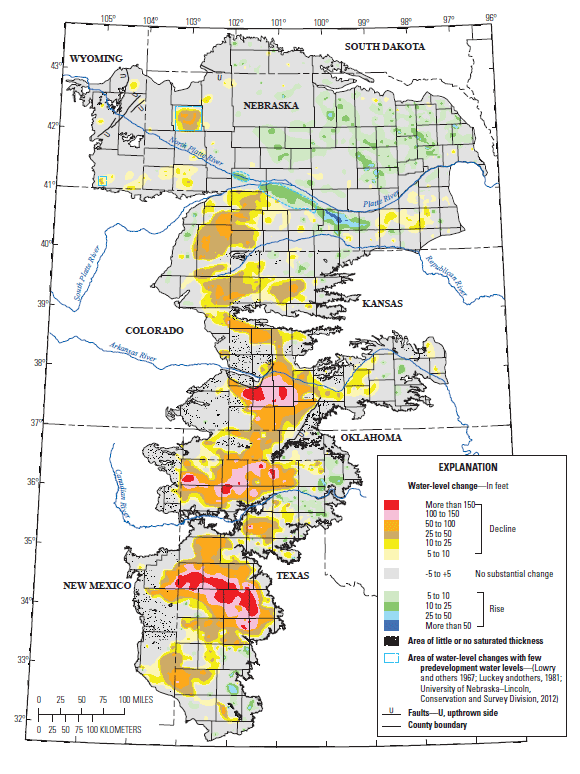

18 March 2013 (Stateline) – Threatened by another summer of crop-shriveling drought, Kansans are watching a bold experiment unfold in Sheridan County, population 2,556, a sliver of the state’s northwest corner. On lands dominated by agriculture, locals have agreed to across-the-board cuts to water use. The state of Kansas didn’t order the cuts, nor did a regional entity. Rather, at a time when states and locals are jockeying for water, stakeholders in the 100 square-mile “high priority” (meaning particularly parched) zone of Northwest Kansas Groundwater District 4 reached a consensus to reduce groundwater pumping by 20 percent over the next five years. They are gambling on short-term wants for a longer-term need — to preserve the aquifer their lives depend upon. “We’re doing it because we think it’s right,” said Wayne Bossert, the district’s manager. “We have high hopes for it.” Sheridan’s plan is just one of many major efforts to fend off a slow-moving disaster with national implications: The High Plains Aquifer, which feeds some of the world’s most productive croplands, is running dry. The aquifer, also called the Ogallala, is one of the world’s largest underground sources of freshwater. It stretches 174,000 square miles through the middle of the country from South Dakota to Northwest Texas, touching parts of Kansas and five other states, watering more than one-quarter of all irrigated acreage in the U.S. and some of world’s largest grain cattle feedlots. The Ogallala also provides drinking water to four of every five people living above it. For decades, farmers and others have been slurping up groundwater far faster than nature can recharge it. Since Americans first began to seriously irrigate the Great Plains, beginning in the 1940s, water levels across most of the Ogallala have fallen at least five feet, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Almost one-fifth of the area has dropped at least 25 feet, while 11 percent has lost 50 feet or more. In some of the worst-off areas of Kansas and Texas, the water table has declined as much as 200 feet. The most recent drought has compounded the problem, drying up riverbeds and forcing farmers to rely even more heavily on groundwater. It can take as long as 6,000 years for water to percolate through the thick layers of earth and rock separating surface from aquifer. In most areas, pumping the water is akin to mining iron or copper; once removed from the ground, the resource doesn’t come back. “It’s kind of a ticking time bomb, and we kind of know it,” said Kent Askren, a water specialist with the Kansas Farm Bureau. “We’re trying to squeeze every ounce of every drop we apply.” Researchers and officials have been aware of the Ogallala’s condition for decades, but the drought gripping the region has put it, and other water issues, into sharp focus. Groundwater districts are looking for ways to slash water use, and states aim to incentivize and support those decisions.

- In 2012, the Kansas legislature recently passed a slew of new water laws, including one making Sheridan’s plan possible. It’s now examining whether to tweak those policies.

- In Nebraska, lawmakers are considering spending $3 million for a task force to study the state’s water needs and recommend projects to meet conservation goals.

- In rapidly growing Texas, the legislature is considering investing some $2 billion into building reservoirs and other infrastructure recommended in the state’s long-underfunded water plan.

If the Ogallala dries up? Folks in the region don’t mince words. “That would be devastating,” said Nebraska state Sen. Tom Carlson, who has proposed the task force. “We can’t let it happen. We won’t let it happen.” “The implications are profound,” said Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback in an interview. “It is time to act.” [more]

In Drought Ravaged Plains, Efforts to Save a Vital Aquifer