Global warming study maps coral reef vulnerability – Reducing carbon emissions would delay annual bleaching events by more than two decades in 23 percent of the world’s reefs

By Bob Berwyn

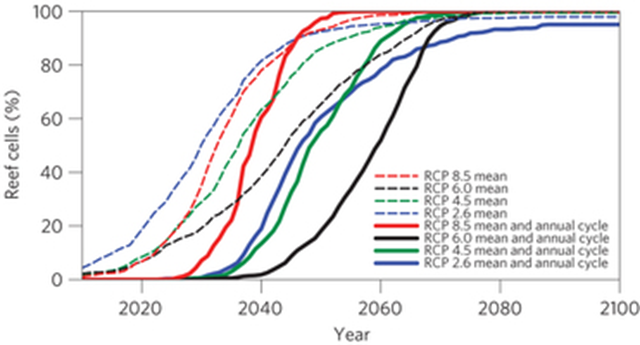

26 February 2013 FRISCO (Summit Voice) – Using the latest data from the upcoming IPCC climate assessment, ocean researchers have concluded that about three-quarters of the world’s coral reefs could face annual bleaching events in just a short 30 years, and they’ve mapped out which areas will be hit first. “This study represents the most up-to-date understanding of spatial variability in the effects of rising temperatures on coral reefs on a global scale,” said researcher Serge Planes, Ph.D., from the French research institute CRIOBE in French Polynesia. Large-scale bleaching events on coral reefs are caused by higher-than-normal sea temperatures. High temperatures make light toxic to the algae that reside within the corals. The algae, called zooxanthellae, provide food and give corals their bright colors. When the algae are expelled or retained but in low densities, the corals can starve and eventually die. Bleaching events caused a reported 16 percent loss of the world’s coral reefs in 1998 according to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network. The findings show that, without significant reductions in emissions, most coral reefs are at risk. Reducing carbon emissions would delay annual bleaching events more than two decades in nearly a quarter (23 percent) of the world’s reef areas, the research shows. About a quarter of coral reefs are likely to experience bleaching events annually five or more years earlier than the median year, and these reefs in northwestern Australia, Papua New Guinea, and some equatorial Pacific islands like Tokelau, may require urgent attention, the researchers warned. […] “Our projections indicate that nearly all coral reef locations would experience annual bleaching later than 2040 under scenarios with lower greenhouse gas emissions.” said Jeffrey Maynard, Ph.D., from the Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de l’Environnement (CRIOBE) in Moorea, French Polynesia. “For 394 reef locations (of 1707 used in the study) this amounts to at least two more decades in which some reefs might conceivably be able to improve their capacity to adapt to the projected changes.” […] The study was published this week in Nature Climate Change. [more]