Rising acidity levels threaten ocean food chain, study finds

26 November 2012 (SMH) – The shells of some marine snails in the seas around Antarctica are dissolving as the water becomes more acidic, threatening the food chain, a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience said on Sunday. The tiny snails, known as ‘‘sea butterflies’’, live in the seas around Antarctica and are left more vulnerable to predators and disease as a result of having thinner shells, scientists say. The study presents rare evidence of living creatures suffering the results of ocean acidification caused by rising carbon dioxide levels from fossil fuel burning, the British Antarctic Survey said in a statement. ‘‘The finding supports predictions that the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs may be significant.’’ The tiny snail, named for two wing-like appendices, does not necessarily die as a result of losing its shell, but it becomes an easier target for fish and bird predators, as well as infection. This trend may have a follow-through effect on other parts of the food chain, of which they form a core element. The world’s oceans absorb more than a quarter of man-made carbon dioxide emissions, which lower the sea water pH. Since the beginning of the industrial era, our oceans have become 30 per cent more acidic, reaching an acidity peak not seen in at least 55 million years, scientists say. Scientists discovered the effects of acidification on the sea butterflies from samples taken around the Scotia Sea region of the Southern Ocean in February 2008. Oceans soak up about a quarter of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere each year and as CO2 levels in the atmosphere increase from burning fossil fuels, so do ocean levels, making seas more acidic. Ocean acidification is one of the effects of climate change and threatens coral reefs, marine ecosystems and wildlife. The study involved researchers from the British Antarctic Survey, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other institutions found. “The corrosive properties of the water caused shells of live animals to be severely dissolved and this demonstrates how vulnerable pteropods are,” said lead author Nina Bednarek, from the NOAA. “Ocean acidification, resulting from the addition of human-induced carbon dioxide, contributed to this dissolution.” […]

Rising acidity levels threaten ocean’s food chain, study finds

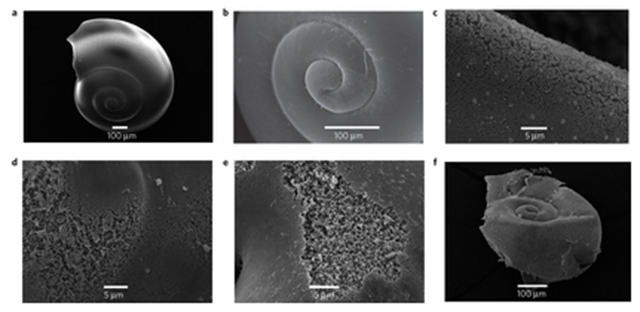

ABSTRACT: The carbonate chemistry of the surface ocean is rapidly changing with ocean acidification, a result of human activities1. In the upper layers of the Southern Ocean, aragonite—a metastable form of calcium carbonate with rapid dissolution kinetics—may become undersaturated by 2050 (ref. 2). Aragonite undersaturation is likely to affect aragonite-shelled organisms, which can dominate surface water communities in polar regions3. Here we present analyses of specimens of the pteropod Limacina helicina antarctica that were extracted live from the Southern Ocean early in 2008. We sampled from the top 200 m of the water column, where aragonite saturation levels were around 1, as upwelled deep water is mixed with surface water containing anthropogenic CO2. Comparing the shell structure with samples from aragonite-supersaturated regions elsewhere under a scanning electron microscope, we found severe levels of shell dissolution in the undersaturated region alone. According to laboratory incubations of intact samples with a range of aragonite saturation levels, eight days of incubation in aragonite saturation levels of 0.94–1.12 produces equivalent levels of dissolution. As deep-water upwelling and CO2 absorption by surface waters is likely to increase as a result of human activities2, 4, we conclude that upper ocean regions where aragonite-shelled organisms are affected by dissolution are likely to expand.

Extensive dissolution of live pteropods in the Southern Ocean