90 percent of oil palm plantations came at expense of forest in Kalimantan

By Jeremy Hance

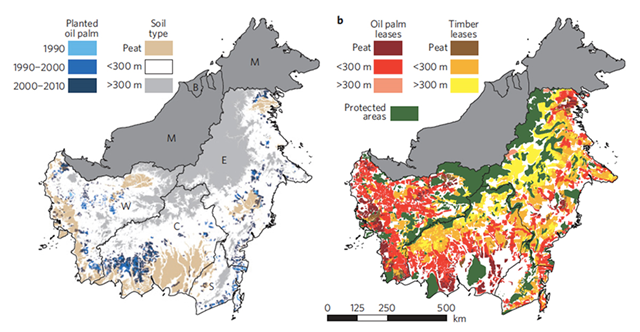

8 October 2012 (mongabay.com) – From 1990 to 2010 almost all palm oil expansion in Kalimantan came at the expense of forest cover, according to the most detailed look yet at the oil palm industry in the Indonesian state, published in Nature: Climate Change. Palm oil plantations now cover 31,640 square kilometers of the state, having expanded nearly 300 percent since 2000. The forest loss led to the emission of 0.41 gigatons of carbon, more than Indonesia’s total industrial emissions produced in a year. Furthermore the scientists warn that if all current leases were converted by 2020, over a third of Kalimantan’s lowland forests outside of protected areas would become plantations and nearly quadruple emissions. “Carbon emissions solely from oil palm industries may therefore constrain opportunities to meet Indonesia’s pledged 26% reduction below projected 2020 greenhouse gas emissions levels,” the researchers write. Currently, over 75 percent of Indonesia’s emissions are connected to land use change. To help slow its runaway emissions, Indonesia has kick-started a moratorium on forest clearing with a billion dollars in funding from Norway, however the moratorium has been widely critiqued for not being strong enough to slow rampant deforestation. Delving into unprecedented detail, the researchers calculated that 47 percent of oil palm plantation development from 1990 to 2010 in Kalimantan was at the expense of intact forests, 22 percent at secondary or logged forests, and 21 percent at agroforests, a mix of agricultural land and forests. Only 10 percent of expansion occurred in non-forested areas.

“A major breakthrough occurred when we were able to discern not only forests and non-forested lands, but also logged forests, as well as mosaics of rice fields, rubber stands, fruit gardens and mature secondary forests used by smallholder farmers for their livelihoods,” explains Kimberly Carlson, a Yale doctoral student and lead author of the study. “With this information, we were able to develop robust carbon bookkeeping accounts to quantify carbon emissions from oil palm development.” From 1990-2000 deforestation for plantations resulted in 0.09 gigatons of carbon, but expanding plantations increased that by over 300 percent during the last decade to 0.32 gigatons. Carlson and her team used satellite imagery and new vegetation classification technology created by Gregory Asner from the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology, who appears as a co-author in order to compile just how much forest was lost and carbon emitted. After crunching the number for 1990-2010, the team then moved onto the future of the palm oil industry and forests in Kalimantan. Gathering oil palm land leases, the scientists found that only 20 percent of current leases had been developed. Unplanted leases still covered 93,844 square kilometers, an area larger than Hungary. “Leases are awarded without independent assessments of land use and carbon, and are not available for public review,” the authors write. “Carbon emissions from undeveloped leases have therefore remained concealed and excluded from national emission projections.” The development of all of these hidden leases, many of which remain unknown to locals as well, would result in 1.52 gigatons of carbon released into the atmosphere. Furthermore oil palm plantations would then cover 34 percent of land in Kalimantan outside protected areas, which currently cover about 10 percent. “These plantation leases are an unprecedented ‘grand-scale experiment’ replacing forests with exotic palm monocultures,” says co-author Lisa M. Curran, a professor of ecological anthropology at Stanford and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “We may see tipping points in forest conversion where critical biophysical functions are disrupted, leaving the region increasingly vulnerable to droughts, fires and floods.” The study finds that protecting peatlands and forests could greatly decrease projected emissions. Protecting peatlands would reduce estimated emissions over the next decade by 37-45 percent, while protecting forests actually decreased emissions from 71-111 percent. Since aging oil palm plantations store some carbon, a gain in carbon is possible if natural forests are protected. Furthermore, the study found that REDD+ programs could be economically competitive with oil palm. […]

90 percent of oil palm plantations came at expense of forest in Kalimantan