Georgia governor declines to declare drought

By Neela Banerjee

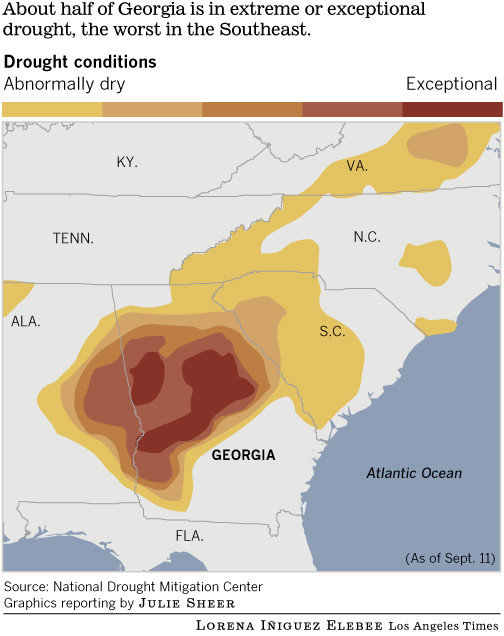

16 September 2012 FAYETTEVILLE, Georgia (Los Angeles Times) – In this southern suburb of Atlanta, the lawns skirting the million-dollar homes are lush, and the swimming pools full. But farther south, the Flint River has thinned into mud flats at a time of year when surges of white water would normally be crashing over boulders in the riverbed. Depending on whom you ask, Georgia is doing fine, or it’s suffering from historic drought. Georgians have gotten a swift education: Since 1999, the state has spent more years in drought than in normal conditions. Federal maps show that more than half of Georgia is now in extreme or exceptional drought, at a time when 70% of the country is experiencing abnormal aridity. But the state’s relentless experience with drought has created ambivalence among residents and policymakers about how to cope with it, hinting at problems other states may have to face if their droughts drag on or recur with troubling regularity. Environmentalists, scientists and farmers point to places like the Flint, as well as reservoir levels and stream and rainfall data as proof of drought. Republican Gov. Nathan Deal and much of the business community contend that there is no drought. Unlike his predecessor, Deal has yet to declare one. The state’s resistance to more drastic measures stems from its desire to protect its business-friendly image, critics say. “Atlanta is the brightest symbol of the ‘New South,’ and the Southern miracle depends on the use of natural resources,” said Gordon Rogers, executive director of Flint Riverkeeper, an environmental group. “And the key resource is water.” Large parts of Georgia this year have gotten about half to two-thirds of the rain they normally get. Some of the state’s biggest lakes and reservoirs are 9 feet or more below their typical summer levels. Georgia’s political and economic priorities are mostly set by the greater Atlanta area in the north, home to about 4.2 million people, making it hard for the needs of smaller communities in the southern part of the state to be addressed. The last drought, in 2007-08, hit metro Atlanta harder than this one. So, the state took dire steps to ensure adequate water supplies. Then-Gov. Sonny Perdue, a Republican, rallied folks to pray for rain. But Georgians say what mattered most was that Perdue talked up the drought. People tweaked their daily lives to conserve water, like taking shorter showers or turning off the tap when brushing their teeth. More controversially, Perdue made an official drought declaration and imposed strict restrictions on how much and when people could water their lawns. Along with the recession, the watering ban pummeled one of the state’s largest industries, so-called urban agriculture, which includes turf grass and landscaping, leading to layoffs and bankruptcies. This time, the $8-billion-a-year industry was spared what Georgia Agribusiness Council President Bryan Tolar calls the “knee-jerk reaction” of the watering ban. Banning outdoor watering now, which largely affects the densely populated metro area, would not help ease the drought in southwestern Georgia, state officials said. “A gallon of water saved in the metro Atlanta area would fail to ensure that there would be adequate water for human consumption in southern parts of the state,” said Napoleon Caldwell of the state Environmental Protection Division. But some hydrologists disagree. They say that conservation upstream would help water quality downstream, which deteriorates during drought, because less water would be discharged as wastewater. Another move that critics say betrays a pro-business approach to the water issue is Deal’s annexation of the state climatologist’s office into his administration from its historical perch at the University of Georgia. Some contend that the shift limits the office’s independence and is part of the administration’s broader effort to play down the drought. The Deal administration denies the allegation. Yet since the annexation, scientists say, Georgia has provided less detailed information to a federal drought monitoring site, which means a less accurate depiction of drought in the state. Georgia climatologist Bill Murphey said his office continues to supply reliable data and “insight when asked and where asked.” […]