In fragmented Brazil forest, few species survive – ‘The results are actually pretty gloomy’

By KELLY SLIVKA

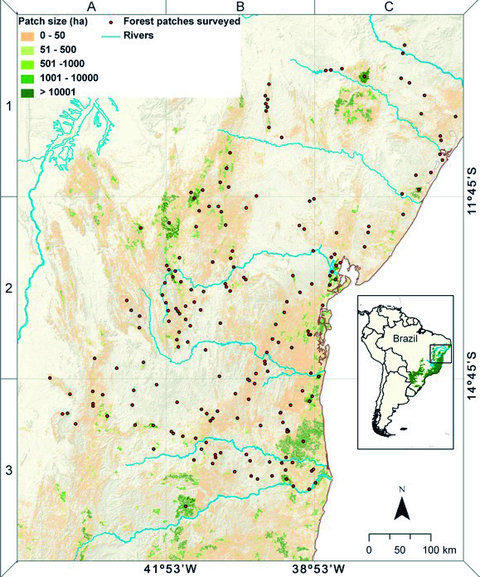

14 August 2012 The Atlantic Forest in Brazil, which runs along the country’s southeastern shore near Rio de Janeiro, has been fragmented by centuries of human habitation. While the rain forest originally spanned over half a million square miles – an area comparable to the size of South Africa – almost 90 percent of it is now gone. Fields, roads, and cities have taken the place of trees. Pockets of forest that survived clear-cutting and fires are scattered across the original domain of the forest. Some are the size of a football field, some half the size of Long Island, and although they are small by comparison with the forest’s former dimensions, they remain important refuges for the enormous biodiversity that the region still boasts. Yet these scattered patches are not providing many important species the protection that they need to thrive, according to a study published online on Tuesday in the journal PLoS One. Researchers quantified the presence of 18 types of mammals in a sample of 196 Atlantic Forest patches and found that only about 22 percent of the animals that originally inhabited the areas continue to survive there. “Five large mammal species – tapirs, giant anteaters, jaguar, wooly spider monkeys and white-lipped peccaries — are essentially extinct throughout the whole region,” said Carlos Peres, an ecologist at the University of East Anglia in Britain and one of the study’s authors. While ecologists expected that species would have a harder time propagating once their habitat is so greatly reduced, the calculations by Dr. Peres and his colleagues indicated that far fewer survive in the forest patches than typical ecological models have estimated in the past. These models, referred to as species-area relationships, projected that about 47 to 83 percent of the animals that once lived in the forest remain in the patches, versus the 22 percent reported in the study. The discrepancy points up the shortcomings of species-area relationships when it comes to accounting for the human factor, Dr. Peres suggested. Models “rarely consider the effects of exploitation,” he said, and hunting is a common practice in what remains of the Atlantic Forest. Monkeys, sloths, jaguars and pumas can be killed either for food or because they threaten livestock in nearby human settlements. To determine how many animals inhabit the forest patches, Dr. Peres and his colleagues spent two years driving over 120,000 miles of roads through the landscape that once was the Atlantic Forest. They surveyed the patches for animals, but they mostly relied on interviews with locals, asking them how many animals they tended to see over a period of time. (Many of the animals the researchers were searching for are elusive, so tapping the stored knowledge of residents saved time, Dr. Peres said.) The researchers then used their own sightings in the patches to ground-truth the information they received in interviews. “The results are actually pretty gloomy,” said Dr. Peres, a native of the Amazon region who now lives in Britain. “We tend to spend more conservation dollars in the Atlantic Forest than anywhere else in Brazil,” he said, so it was disheartening to learn that these mammals are disappearing all the same and at a faster rate than ecologists had thought. […]