Video: In Louisiana, rising seas threaten Native American lands

By Hari Sreenivasan

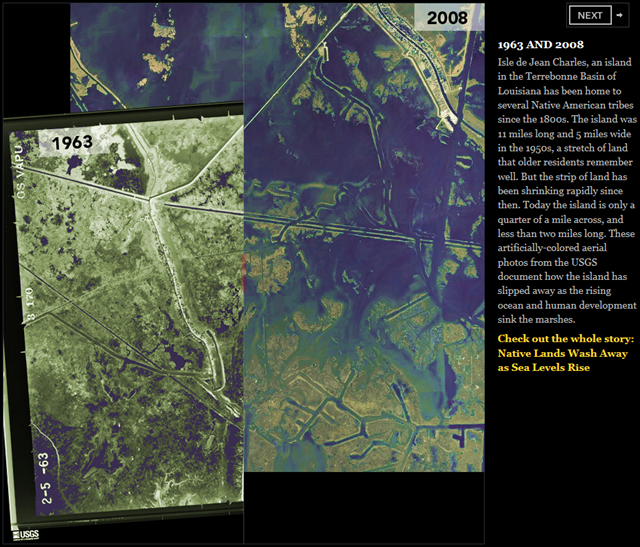

1 June 2012 MARGARET WARNER: Now: Coping With Climate Change. In this edition of our series, Hari Sreenivasan reports from the Louisiana Gulf Coast, where rising seawater is claiming the land people have lived on for centuries. Louisiana Public Broadcasting was our partner in this report. HARI SREENIVASAN: It used to be a long walk for Theresa Dardar to reach her ancestors’ cemetery here in coastal Louisiana. We had to take a boat ride with her to visit the burial site that is surrounded by water, because coastal Louisiana is sinking and the sea level around it is rising. THERESA DARDAR, Pointe-au-Chien Tribe Member: We’re not going to have anything for our children to see, you know, if it keeps on washing away, if they don’t try to stop it some kind of way. So, they will never see what we saw. HARI SREENIVASAN: Dardar is a member of the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe. Her tribe and several others settled on the edge of Louisiana in the 1840s. That’s when the Indian Removal Act forced thousands of Native Americans off their land. They headed south and west to the bayou. Now different forces are taking their land away again. Albert Naquin knows the sea is coming for his ancestral home. How much of this was all land? All that water that we’re seeing out there? ALBERT NAQUIN, Biloxi-Chitimacha Chief: All that water was land. Actually, it was — it was basically all land, except for a few ponds here and there. HARI SREENIVASAN: Isle de Jean Charles is a narrow ridge of land located in Terrebonne Parish. It is home to a native community descending from Choctaw, Houma, Biloxi, and Chitimacha Indians. Naquin is chief and grew up on the island. He left several years ago when the rising waters’ damage to his home and livelihood became overwhelming. ALBERT NAQUIN: I was born there in 1946. HARI SREENIVASAN: And what was life like? ALBERT NAQUIN: Life was good. Life was — it was like paradise, actually. If I was to be reborn again as a child, I would want to be raised there, if the community was like it was back in 1946. HARI SREENIVASAN: In the 1950s, the island was 11 miles long and five miles across. Now it is no more than two miles long and a quarter-mile across. Where residents once used to trap, hunt and plant gardens, dead trees stand in ghost forests because their root systems were unable to adapt to the saltwater intruding from the Gulf.

Alex Kolker studies what is happening here. He teaches coastal geology at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium. ALEX KOLKER, Professor of Coastal Geology, Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium: The ground at which Louisiana sits on is sinking, and it’s sinking at a relatively high rate. HARI SREENIVASAN: He says some of the reasons that the land is sinking and eroding so quickly are manmade ones. In the 1920s, people built levees to channel the mighty Mississippi River. That prevented floods, but robbed the marshlands of necessary sediment. Without sediment, the barrier islands and wetlands that protected the coast from intense storms sank into the Gulf. The marshes were damaged even more by decades of oil exploration. From the air, you can see the miles and miles of canals that were used to transport fuel out. Even after the wells were shut down, the canals remained open, leaving pathways for the saltwater of the ocean to eat away at the freshwater wetlands. Now the rising sea level has added to the problem. The average sea level in Southeast Louisiana is rising at a rate of three feet every 100 years. That is according to 60 years of tidal gauge records. That’s unusually high, say scientists like Torbjorn Tornqvist of Tulane University. TORBJORN TORNQVIST, Geoscientist, Tulane University: Prior to the Industrial Revolution, The rates of sea level rise along the Gulf Coast was about five times lower than it has been in the last century. The rates we see nowadays are high enough that the last time we — this whole region experienced rates like at that rate is more than 7,000 years ago. And that’s a time when we still had a big ice sheet here in — further north in North America that was melting at very high rates. That was the main cause of that rapid sea level rise. HARI SREENIVASAN: Scientists say that, as the Earth’s temperature increases, the oceans also warm and water expands. The combination of rising oceans and sinking land means that Louisiana’s coastal sea level is rising at a higher rate than other coastal areas, says Alex Kolker. ALEX KOLKER: South Louisiana has experienced rates that may be on the order of several centimeters a year, so maybe up to an inch a year in some cases. HARI SREENIVASAN: And the results of all that water are stark. In just the last 100 years, Louisiana’s coast has lost 1,900 square miles of land. That’s an area of land the size of Manhattan lost every year, or a football field every hour. ALEX KOLKER: And so I think that the lesson that South Louisiana — that South Louisiana can provide to the nation is what a high rate of sea level rise can do to the coast. And that is, it can convert land into open water. It can allow storm surges to propagate further inland and be destructive to infrastructure and even people’s lives. HARI SREENIVASAN: It is a hard lesson and may get even harder. The state of Louisiana recently drafted its own 50-year plan to restore the coast. State officials admit that maintaining the current coastline may be next to impossible, and they are trying to prepare for scenarios in accordance with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s reports, which predict that sea level rise will accelerate in the next century. But what does that mean for the native residents? Many here lack the resources to leave. Several tribes in the region are not recognized by the federal government, meaning they have no access to the assistance and benefits entitled to other native peoples. Remaining residents like Doris Naquin say they are rooted on the island. […]