As politicians debate climate change, our forests wither

By Sophie Quinton, staff reporter (politics) for National Journal

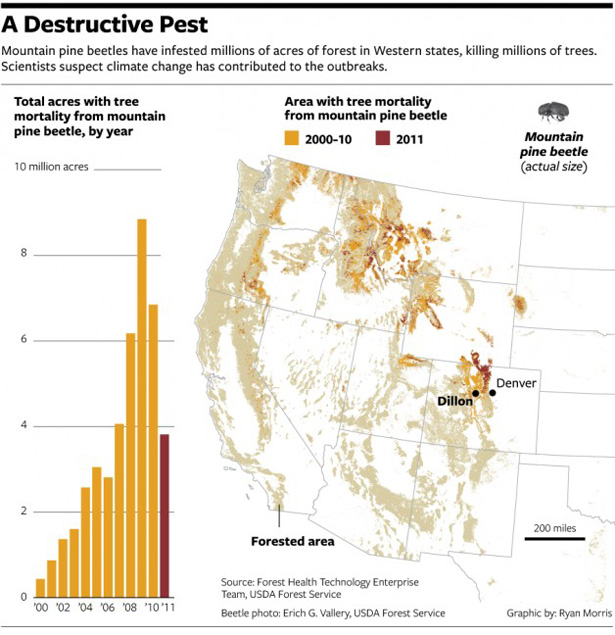

15 June 2012 DILLON, Colorado – Dan Gibbs keeps dead beetles in the back of his beat-up Chevy Silverado. He has a wooden block with beetles impaled on it, each insect about the size of a grain of rice. He’s got vials of embalmed beetles and their larvae. He carries around pieces of wood that show what those tiny beetles do to a mature lodgepole pine: They drill deep into the trunk and infect the tree with a fatal fungus that stains its wood blue. Gibbs isn’t a scientist. He’s a commissioner for Summit County, a high-altitude slice of Colorado that’s gaining fame as a ground zero, of sorts, for an epidemic that has devastated pine forests across North America. Twenty years ago, the mountainsides around Dillon were a lush green; these days, they’re gray with needle-less trees. The pine-beetle epidemic provides perhaps the most visual evidence of climate change in the United States. But that evidence, while arresting, remains circumstantial. Scientific studies linking the factors that drove the epidemic to rising global temperatures haven’t convinced everyone, let alone prompted people here to forsake fossil fuels. It isn’t just the dead trees. Here, near the headwaters of the Colorado River, the snow is melting earlier–and there’s less of it. Summers are drier. Threats of wildfire and water shortages have grown, changing lives and livelihoods in Colorado and across the West. Still, it’s not simple to draw a bright line from observable phenomena to climate change. For some policymakers, the lack of clarity is frustrating. Mounting evidence that the planet is warming and that human activity is to blame hasn’t generated any sort of political momentum for action, even as, in places like Dillon, forests are dying in plain sight. As people here struggle to understand the beetle epidemic, the term “climate change” has become so inflammatory that few even utter it. It’s also unclear to residents what, exactly, they would accomplish by reducing their fossil-fuel use. Without a more far-ranging plan of attack on a national–indeed, international–scale, all that people in Dillon and places like it can do is adapt to changing circumstances. Gibbs keeps beetles in the back of his pickup to teach people about forest health, not to start a conversation about climate change. (And he, like almost everyone in the mountains, drives a gas-guzzling truck.) “Does climate change play a role in it? For sure, I think,” Gibbs said of the pine-beetle epidemic. But, he added, “I think scientists are still really studying it.” […]